Taking a cue from its Los Angeles location, the CAS 2023 Annual Meeting included two general sessions focused on California’s market. The Tuesday morning’s session, “California Dreaming: Earthquakes, Wildfire and Floods,” focused on the three highest-profile perils in the state: earthquakes, floods and wildfire. California is the largest insurance market in the U.S., and these three perils are all low-frequency, high-severity events. This contributes to the challenges of adequately pricing and underwriting insurance to cover these risks.

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) designed and built the National Risk Index (NRI) for 18 natural hazards. Per the FEMA website, “The NRI is an easy-to-use, interactive tool that shows which communities are most at risk to natural hazards. It includes data about the expected annual losses to individual natural hazards, social vulnerability and community resilience, available at county- and Census-tract levels.” In short, FEMA has created a powerful resource for anyone involved in any aspect of catastrophe management.

The general session moderator and speakers used the NRI as the framework for their presentations. Session Moderator Carl Ashenbrenner, FCAS, of Milliman, Inc., opened with an overview of the NRI that included several maps highlighting the significant amount of exposure value and expected annual losses (EAL) in California for all hazards. He then introduced the three speakers: Shawna Ackerman, FCAS, from the California Earthquake Authority (CEA); Andy Neal from Aon; and Sheri Scott, FCAS, CSPA, from Milliman, Inc. Each speaker focused on one of the perils.

Ackerman led off with a deep dive on earthquakes. The NRI includes EAL modeled using Hazus 6.0. Two-thirds of the U.S. earthquake EAL occurs in California, and 78% in the combined Pacific Rim states of California, Washington and Oregon. She highlighted the notorious San Andreas fault running east of L.A. and a network of over 100 other faults across the region. Based on return periods from prior events, Southern California is overdue for a major earthquake.

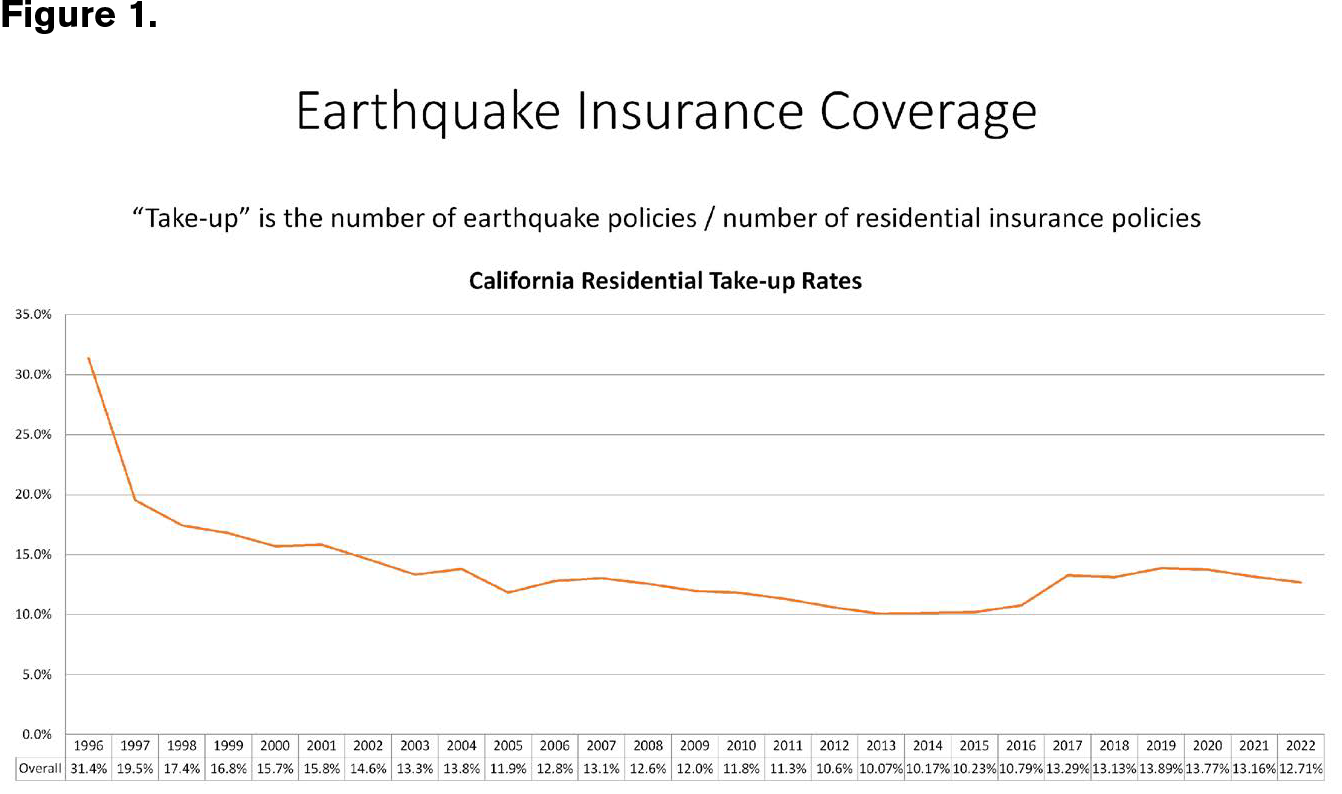

With that background, Ackerman then segued into the insurance aspects of this unique peril. Most importantly, mortgage lenders do not require homeowners to purchase earthquake coverage. So, the “take-up rate” on earthquake insurance, which primarily covers losses caused by shaking, has hovered between 10%-15% from 2002-2022 after peaking above 30% following the Northridge earthquake in 1994. (See Figure 1.) Note that fire losses following an earthquake are covered by traditional all-perils homeowners policies, and tsunami losses are covered by flood policies.

She concluded her presentation by recounting the public policy and insurance industry responses after major California quakes, which are of particular interest for students of history. The timeline started from the great 1906 San Francisco earthquake, which spawned the state’s first monitoring program, and ran through the 1994 Northridge event, which led to an availability crisis and creation of the CEA as a public-private partnership. Today, the CEA provides two-thirds of the residential earthquake insurance policies sold in California.

Neal then shifted the conversation to flood risk, given his experience at FEMA and involvement in the creation of the NRI. In contrast to earthquake and wildfire perils, riverine flood EAL in the NRI is based on historical data instead of a prospective risk model, which can lead to an understated view of risk in areas where the historical record lacks representation of larger, less frequent flooding. That said, the recently implemented Risk Rating 2.0 was FEMA’s attempt to bring actuarially sound risk-based pricing to the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) using prospective private sector and public sector risk models.

His brief history of flood risk emphasized key events following severe river floods or major hurricanes. For example, an 1862 river flooding led to the nation investing in significant levees around major waterways. Flood risk in California derives most prominently from its many rivers, most notably in the central valley, so levees were built around much of the state with mixed results. After the 1927 Great Mississippi River flood, the nation began to adopt a more holistic approach, including floodplain management and structural retrofitting for mitigation.

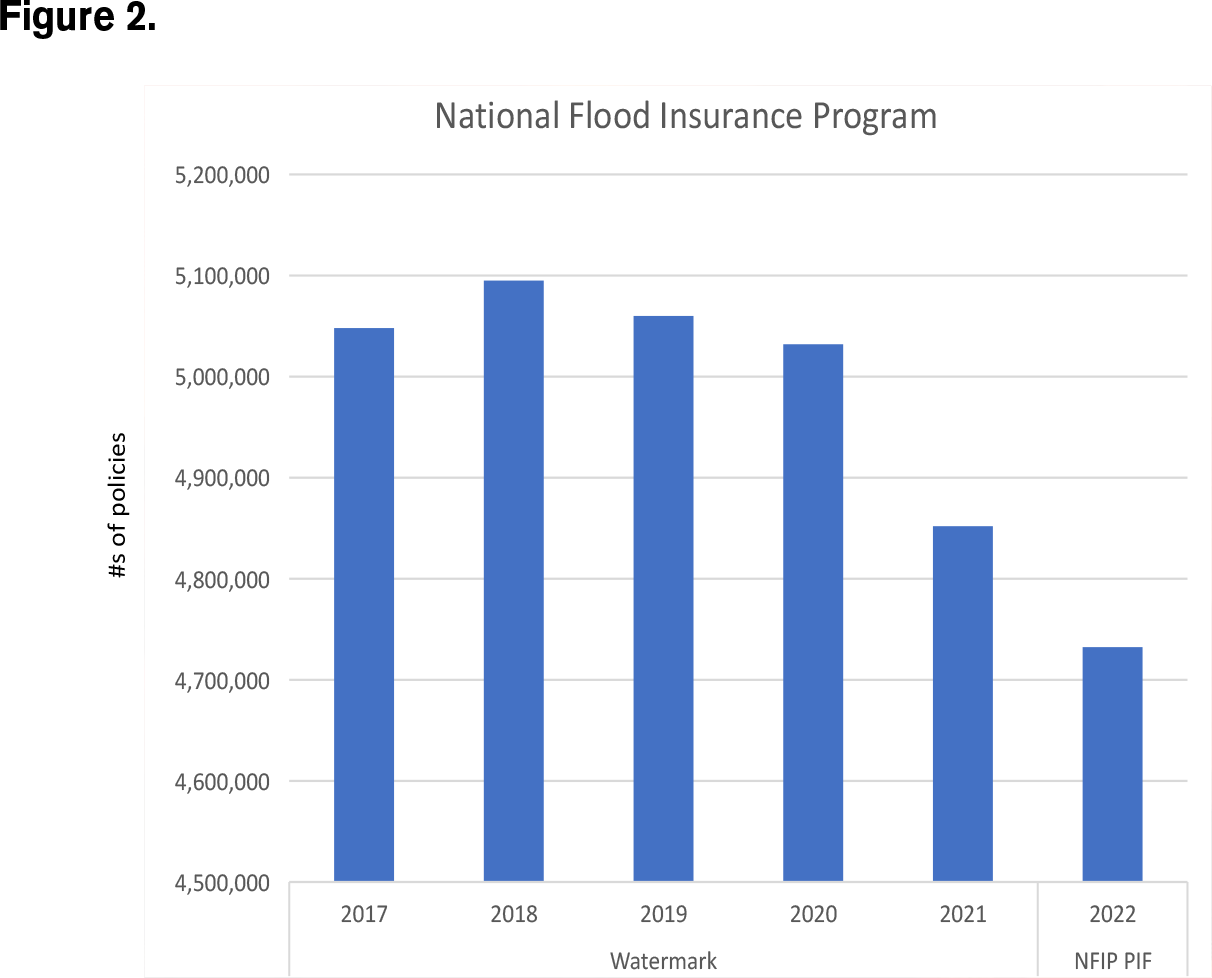

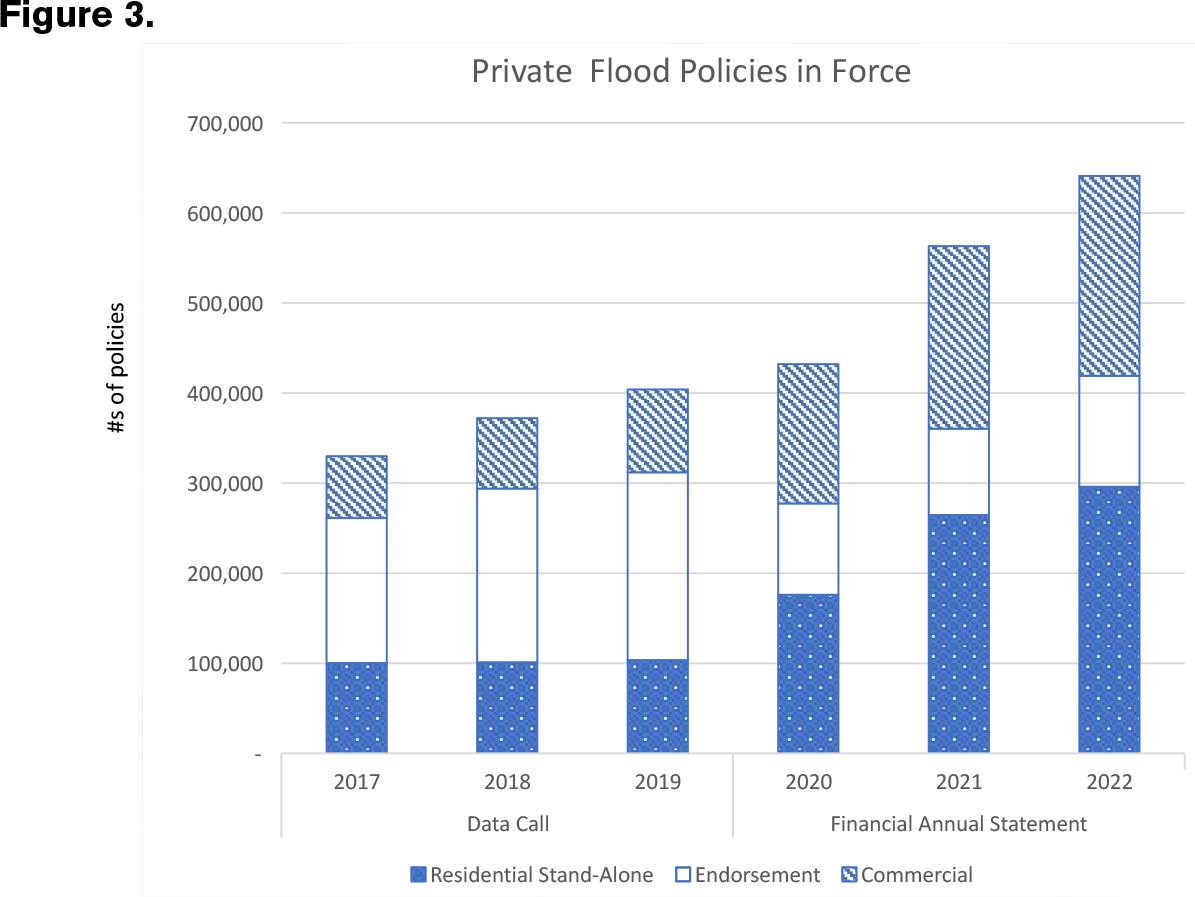

After major southern hurricanes in 1962 and 1963 led to an insurance availability crisis, the Federal Flood Insurance Act of 1968 led to the creation of the NFIP. For the next 50 years, the NFIP was the primary U.S. insurer of flood risk, although take-up rates nationally were very low. Homeowners in designated flood zones were required to purchase the coverage, but the take-up rate even in these zones was still not universal. As captured in Figures 2 and 3, the private market for flood coverage has grown in the last five years, while the NFIP’s market share has declined. The growth of the private market may account for some of the NFIP’s decline.

watermark-financial-statements and NFIP Policies in Force (PIF) Rolling History as of

9/30/2023 Force https://nfipservices.floodsmart.gov/reports-flood-insurance-data.

Statement Data, 2018-2019 from Policies in Force end of CY Data Call, 2017 from Policies in

Force end of PY Data Call

Scott then delved into the complexities of wildfire risk. California has the highest wildfire EAL of any state. The number of severe wildfires is increasing with climate change, more residences being built in the wildland urban interface (WUI) and increases in the replacement costs of homes. Relying on historical data solely will underestimate the statewide prospective risk and over- or understate the prospective risk of individual structures, depending on whether or not they have been in the footprint of prior events.

Unlike earthquake and flood, wildfire is covered by standard all-peril homeowners’ insurance policies. This requires every insurer writing this coverage to invest in the expertise to appropriately price and underwrite wildfire risk along with other, largely unrelated perils. Wildfire risk contributors include:

- Territorial considerations, including location and proximity to wildlands.

- Property-specific characteristics, including slope, fuel, access, precipitation and winds.

- Structural considerations, including roofing, eaves, vents and windows.

Scott described how the current state of California’s insurance market has been impacted by the following public policy events:

- The 1968 establishment of the California FAIR[1] Plan to address availability challenges after a series of fires in Southern California.

- Passage of Proposition 103[2] in 1988, which required admitted property insurance rates to go through a prior approval process with the California Department of Insurance, with provisions deeming the rates approved after 60 or 180 days, depending on details laid out in the legislation.

- California Code of Regulations (Regulations) which required catastrophe rates to be developed using 20 years of an insurance company’s historical catastrophe losses and which did not allow the insurer to recover the net cost of reinsurance in catastrophe rates. These Regulations allow earthquake and fire following earthquake rates, but not wildfire rates, to be developed using catastrophe models and to consider reinsurance costs.[3]

Even with updated Regulations that allow insurers to use catastrophe models to recognize the wildfire exposure more accurately and give insurers the ability to include the net cost of reinsurance in wildfire rates, there is little relief to insurers being able to charge adequate rates if they can’t get the rates approved.

Scott suggested updating these outdated Regulations as part of the solution to the California property insurance availability crisis, which was created as a result of insurers not being able to keep up with the cost of providing wildfire insurance. However, the outdated Regulations are only part of the problem. Even with updated Regulations that allow insurers to use catastrophe models to recognize the wildfire exposure more accurately and give insurers the ability to include the net cost of reinsurance in wildfire rates, there is little relief to insurers being able to charge adequate rates if they can’t get the rates approved. It has taken over a year, on average, to get a rate filing approved, making it difficult to keep up with the double-digit annual increase in cost to rebuild over the past three years.

The recent implementation of Regulation 2644.9 gives property owners incentives to implement wildfire mitigation measures to receive a reduction in rate on their insurance. However, more education is required for property owners to understand that the cost to mitigate damages to a property, whether it be from wildfire, earthquake or flood, will always be greater than the annual insurance discount, which represents the reduction in average annual expected insured loss cost per property. While a wildfire may not impact a property for many years, if ever, the mitigation may only nominally reduce the expected loss cost each year. The benefit of mitigation, however, is not just insurance discounts that make a marginal contribution to offset the cost, but more importantly that chances increase for the property to survive a catastrophe and more than just possessions — memories and loved ones — may be spared. There is an impact to consumers and society that goes beyond reduction in insurance premiums.

Regulation 2644.9 is a step in the right direction, but not without increased costs to insurers. These costs can include implementing new consumer notifications and keeping up with inspections, such as through licensing arial imagery to confirm that mitigation measures have been met and are being maintained. For some insurers struggling to maintain adequate rate level, implementing wildfire mitigation discounts without the ability to increase their rates to account for these additional costs wasn’t an option, further contributing to the availability crisis.

Another regulatory update to recognize wildfires is the risk-based capital (RBC) model that the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) task force has updated to consider wildfires in a similar manner as it considers hurricanes and earthquakes. The new, more robust RBC model is required to be submitted as information only with the 2023 year-end financial statement RBC model submission so that the regulators can understand the impact before they finalize the changes to the RBC model.

Moderator Ashenbrenner closed this general session by identifying some themes that cut across the three major perils in California. He attributed the stability of the state’s earthquake market to a high level of consumer awareness, strong building codes, the development of a risk-mitigation culture and the availability of advanced risk-management tools. Wildfire and flood insurance markets should stabilize if and when these same benefits are embraced for these perils. In particular, a culture of mitigation to help reduce losses and reliance on actuarial ratemaking techniques have worked towards improving insurance availability.

Dale Porfilio, FCAS, MAAA, is the chief insurance officer for the Insurance Information Institute.

[1] Fair Access to Insurance Requirements

[2] https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/codes_displayText.xhtml?lawCode=INS&division=1.&title=&part=2.&chapter=9.&article=10.

[3] California Code of Regulations, Title 10, Section 2644.5 – Catastrophe Adjustment, “the catastrophic losses for any one accident year in the recorded period are replaced by a loading based on a multi-year, long term average of catastrophe claims. The number of years over which the average shall be calculated shall be at least 20 years for homeowners multiple peril fire.” In summary, Regulation 2644. 5 requires the use of 20 years of historical catastrophe data for admitted insurance property ratemaking and Regulation 2644.4(e) provides an exception that allows earthquake and fire following earthquake ratemaking to use catastrophe models and more modern methods recommended by Actuarial Standards of Practice. Regulation 2644.25 allows admitted earthquake insurance rates to include net cost of reinsurance, but not wildfire.