The CAS strives for its funded research to be timely and applicable to its members’ work. They struck gold when the CAS Research Paper “Catastrophe Models for Wildfire Mitigation: Quantifying Credits and Benefits to Homeowners and Communities” was published on October 25, 2022.

The California Department of Insurance issued a new regulation, effective October 14, 2022, requiring all insurance companies to file homeowners rating factors for wildfire mitigation credits by April 2023. The new California Code of Regulations 2644.9 mandates rating factors for both individual property-level and community-level mitigation. While the wildfire risk is increasing statewide, many details must be navigated for every California homeowners insurance writer to develop actuarially sound wildfire mitigation credits and incorporate them into an actuarially sound rating plan for overall rate adequacy.

The CAS paper was a result of collaborative research between actuaries at Milliman Inc. and catastrophe modelers at CoreLogic Inc., leveraging the strength of both organizations. At the 2022 CAS Annual Meeting, Peggy Brinkmann, FCAS, CSPA, of Milliman and Thomas Larsen of CoreLogic summarized the existential crisis that is California wildfire risk and discussed the ability of catastrophe models to evaluate and quantify the risk. They also gave their analyses to estimate wildfire mitigation credits for a wide range of scenarios.

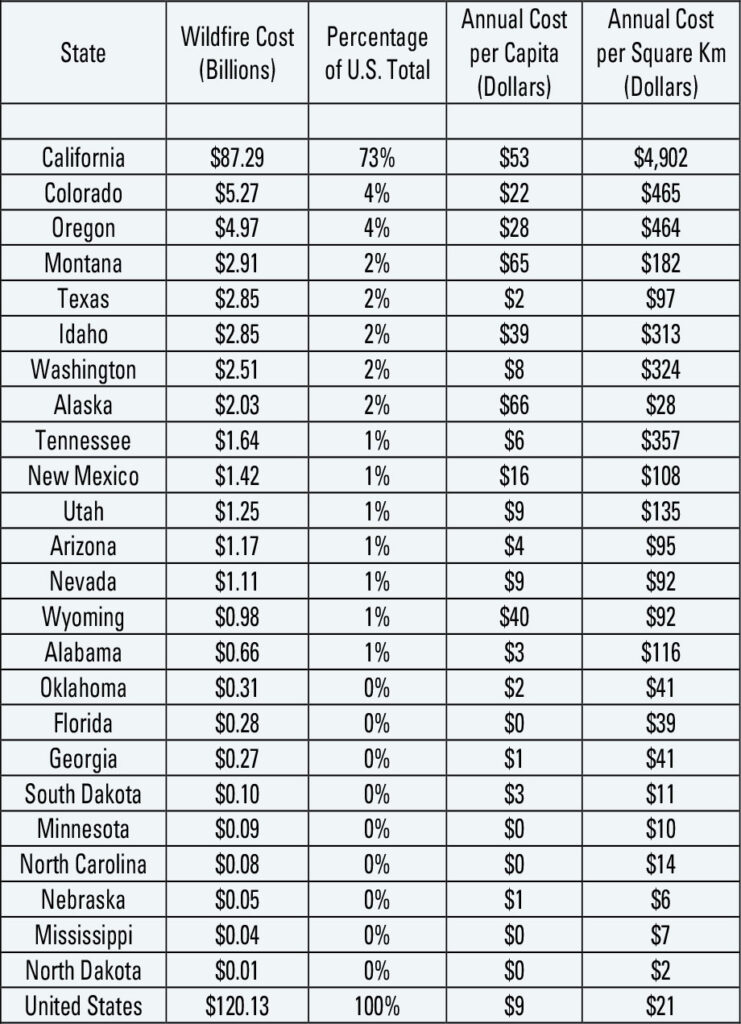

Brinkmann opened the session with an overview of wildfire risk in the U.S., but most poignantly in California. Figure 1 captures the elevated economic cost of U.S. wildfires from 2017-2021, with over 70% of these losses occurring in California alone. This has contributed to insurance availability and affordability challenges for California homeowners. Private insurers have filed for rate increases and tightened their underwriting standards, while the California FAIR Plan policy count started growing rapidly in 2019.

Figure 1. Historical wildfire costs in the United States (2017 – 2021)

The Insurance Institute for Business and Home Safety (IBHS) created the Wildfire Prepared Home program to provide standards for how to reduce the fire risk of individual homes. Their standards contain two key components:

- defensible space — reducing the fire risk in zones around the home.

- home hardening — reducing the fire risk of the home (e.g., roofs, siding, windows).

IBHS has created comparable community mitigation standards, as have the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) through its Firewise USA program and the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) through its Shelter-in-Place recommendations.

This new Milliman and CoreLogic paper includes case studies of individual home and community mitigation credits. They outline the process and the math for an illustrative book of business in the California communities of Orinda and Moraga using generalized linear models applied to the output from CoreLogic’s RQE Wildland Fire model. Their first case study estimated individual home wildfire mitigation credits. They intensely tested myriad combinations of roofing and zone clearance options around the home. Key findings include:

- Roof replacements provide the greatest mitigation benefit, but because they are the most expensive method, they are the least frequently used.

- If a roof cannot be replaced, maintaining clearance zones is the next most impactful action.

- Clearing an area of 30-100 feet from the home of combustible material creates the most effective buffer zone, followed by a zone zero to five feet adjacent to the home.

The paper includes extensive tables of percentage and dollar credits for different combinations of clearance and roof fire classes, which should help actuaries in preparing their own filings.

Their second case study estimated community mitigation credits. These are more complex because homeowners insurance rates must be property-specific, and yet individual homeowners cannot control everything about how a community may choose to mitigate wildfire risk for all its citizens. Milliman and CoreLogic modeled community credits in combination with individual credits to capture this complexity. The paper includes extensive tables of percentage and dollar credits refining the individual credit based on whether they reside in a low-, medium- or high-risk community.

As expected, the model indicates all mitigation measures reduce the individual risk, but individual home mitigation — which individual homeowners control — can have a bigger impact than any community mitigation alone.

Their third case study compares the impacts of individual and community-level mitigation on individual homeowner risks. As expected, the model indicates that all mitigation measures reduce the individual risk, but individual home mitigation — which individual homeowners control — can have a bigger impact than any community mitigation alone.

Brinkmann closed with a quick summary of some implementation challenges for actuaries and California regulators:

- needing to start with adequate rates.

- obtaining data on property-level mitigations.

- acquiring current data on defensible space.

- getting data on community-level mitigation and translating into model inputs.

- avoiding overlap with territory and other rating plans.

All of the items on this list are essential to have actuarially sound prices that balance affordability and availability.

Larsen’s presentation focused on the complexities of wildfire science and how CoreLogic models the risk. The breadth of his content provided new insights for both veterans and novices to wildfire risk. For example, he opened with a recap of the first day of the Camp Fire in 2018, which destroyed the town of Paradise, California. The common element in recent fires is that most damage to property and human life happens in the first eight hours after a wildfire starts, even though it may take many more days for the fire to be fully suppressed.

When it comes to California wildfires, climate risk is causing the future to be far more severe than the past. Fuel (i.e., unburnt vegetation) is increasing every year in large part because fighting forest fires became standard practice after World War II. Summers are getting longer and hotter. Housing growth in Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) continues unabated, including 33% growth in California in the last 20 years. New forestry management mitigation programs are being introduced. In total, planning requires something beyond experience rating.

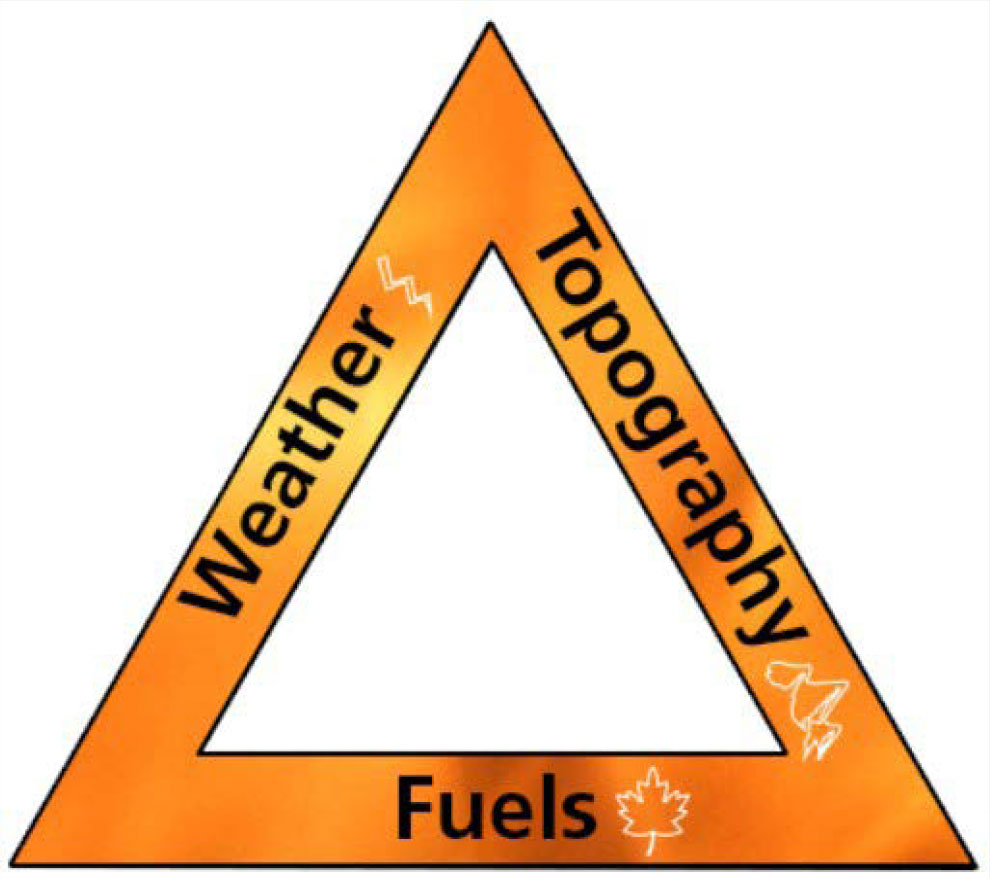

The key elements to a wildland fire are as follows (see Figure 2):

- weather — including temperature, humidity, wind speed and direction.

- topography — shape of the land, elevation, slope and aspect.

- fuels — moisture level, chemical makeup and density (i.e., the degree of flammability).

The worst combination is high fuel around properties on slopes with high winds.

Figure 2. The fire behavior triangle’s three legs are fuels, weather and topography.

When it comes to modeling the physics of a wildfire, the range of possible outcomes is well beyond the historical event set from which modelers can build. Hurricanes have immensely large wind fields and cause a wide range of property damage —from total losses to minor exterior damage. Wildfires are far smaller in size and yet typically cause total losses of dwelling and contents. Further, many locations which today are at significant risk of wildfire have never experienced a prior event. Since 1990 hundreds of thousands of homes have been built in the California Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI), where formerly there were none.

To make this comparison between perils more tangible, Hurricane Andrew generated about two million claims across its full path in 1992. The Northridge earthquake affected about three million homes radiating out from its fault line in 1994. The Camp Fire in 2018 was one of the costliest in history, and it destroyed 18,804 structures before it was fully extinguished.

Larsen provided a brief overview of how CoreLogic modeled the three case studies from the joint paper. This included the different roofing type classes, additional secondary structure modifiers and perimeter clearance. He also covered key mitigation resources and visual examples of homes in need of further wildfire mitigation.

When it comes to modeling the physics of a wildfire, the range of possible outcomes is well beyond the historical event set from which modelers can build.

He closed by recapping three critical aspects of managing and mitigating wildfire risk:

- ignition — Related to human activity, so it can be reduced but never fully eliminated.

- fire spread to homes — Driven by fuels, which can be reduced, and wind which cannot be predicted or controlled.

- home destruction — Homes can be hardened to reduce the risk, but the risk cannot be eliminated so long as properties are built in the WUI.

The CAS Research Paper by Milliman and CoreLogic, as well as Brinkmann’s and Larsen’s presentations, are highly recommended for any actuary or regulator responsible for the pricing and underwriting California properties. Wildfire risk, homeowners and community risk mitigation and insurer risk transfer are intensely complex and will require much attention in the months and years ahead.

Dale Porfilio, FCAS, MAAA, is the chief insurance officer for the Insurance Information Institute.