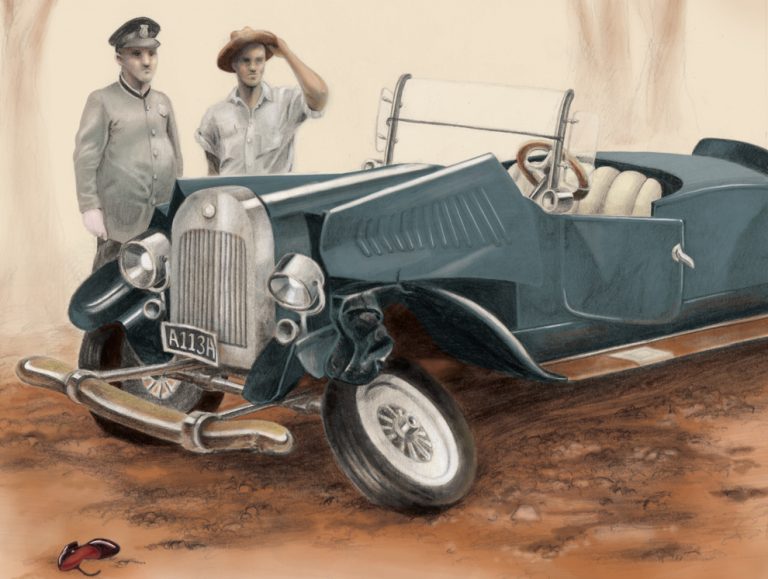

An automobile casualty illustrates the beginnings of how Americans will grasp the unsettling implications of the burgeoning fleet of motor vehicles on the road.

In the hot days of August 1921, my grandfather’s sister, a German-born immigrant named Kunigunde Scholing, left her flat in Manhattan with her four-year-old son for the thick green forests of the Catskills.

Kuni, as family and friends called her, was a summer boarder near the hamlet of Phoenicia in New York’s Ulster County, in one of the many farmhouses catering to city-slicker visitors. But her rustic holiday wouldn’t last very long.

On the evening of August 12, 1921, Kuni and her son joined a small troop of city visitors strolling along the shoulder of a curving, two-lane state highway. They weren’t the only ones out that night. A Packard roadster steadily approached their backs from the south.

As the vacationers meandered past a roadside cemetery, the combination of dark highway, pedestrians and cruising automobile proved predictably violent. Early reports suggest that the group had little time to react when the car plowed into them from behind. Remarkably, Kuni’s little son, walking a few steps ahead of her, escaped without a scratch.

But Kuni was barely alive. Along with two other injured women, she was carried onto the bed of a truck commandeered from a nearby works project, and jolted 30 miles down the highway to a hospital at the county seat of Kingston. Her companions eventually recovered, but Kuni was not so lucky. She died at Kingston three weeks later, never regaining consciousness.

Kuni’s nearly forgotten story springs back to life in newspaper items and court documents with unusual detail for an obscure working-class immigrant. Her death was news for a peculiarly 1920s reason. Kuni was an automobile casualty just as Americans began to grasp the unsettling implications of the burgeoning fleet of motor vehicles on their roads — costs reflected in her widower’s legal struggle to establish accountability and compensation.

As the United States moved beyond the horse-and-buggy era, it was accelerating into a new and dangerous frontier — and everyone was struggling to keep up, the insurance industry included. Consider:

- The rate of automobile ownership in the United States tripled during the 1920s, testimony to a growing fascination with the freedom and mobility of cars.

- New car owners meant many new, inexperienced drivers, with rough-and-tumble results. Ulster County was typical: Within a few weeks of Kuni’s accident, the Kingston newspaper reported that a Studebaker and a Paige sedan cracked up “on the Ashokan boulevard”; that a woman riding on the back of a motorcycle was hurt when a car knocked her off; and that a minister’s car was nearly run off the road by an automobile crammed with raucous young men, apparently drunk.

- In 1921, safety amenities we take for granted today, such as highway stripes, roundabouts, traffic lights and stop signs, were still in the talking stages in most of the country. The first traffic light in New York City would not be installed for another two years.

The “private pleasure car,” which had started the 20th century as an exotic toy for the adventurous and the well-to-do, was muscling its way into everyday life. But nobody was sure what the rules were. When horse-drawn wagons, cars and pedestrians jostled for access, who should be where? If somebody got hurt, how could they be compensated?

Nobody was sure what the rules were. When horse-drawn wagons, cars and pedestrians jostled for access, who should be where? If somebody got hurt, how could they be compensated?

These wide-open questions assumed increasing urgency as the Jazz Age partied on. In 1928, the authors of an article in the University of Chicago’s Journal of Business cast a worried eye on the steady upward trend of auto accident injuries and fatalities over the prior decade. “The evidence indicates quite conclusively that the automobile as an instrument of injury and death has stubbornly defied all of the preventive measures now being employed,” they wrote.

Kuni’s was one of 11,050 auto-related deaths in the U.S. in 1921, compared to 9,097 four years before, according to figures analyzed by the Journal of Business authors. A modern estimate puts the total of U.S. traffic deaths in the 1920s at over 210,000, “three or four times the death toll of the previous decade.”

Such statistics inevitably led to discussions of determining liability and compensation. As the Journal of Business writers wondered: “May it not be that the solution … lies in the further development in [the] field of the insurance method of dealing with risks?”

Good question.

By 1921, motor-vehicle insurance had existed for a while. Travelers wrote the first policy back in 1898. By the time of the first World War, 45 companies were writing this business, as noted by G.F. Michelbacher in a 1918 CAS Proceedings article.

Still, at the time of Kuni’s accident, there was nothing mandatory about insuring a car. The 1920s were the “free-choice” era of auto insurance. As one legal study of motor-vehicle liability in the United States described it: “The early motorist was restricted more in the use of his motorcar than in his option of whether to purchase liability insurance.”

So much for exchanging information and waiting for the claims adjuster. Going to court was a more likely route for redress, assuming the driver who hit you had any ability to pay.

“May it not be that the solution … lies in the further development in [the] field of the insurance method of dealing with risks?”

—Journal of Business, 1928

That was the route taken by Kuni’s widower, William Scholing, who, a few weeks after her death, brought suit in Ulster County for $50,000 (about $650,000 in present-day dollars) against the owner of the Packard involved in the accident. According to newspaper accounts, this was Charles R. O’Connor, a member of a prominent family in neighboring Delaware County and a former federal Prohibition enforcement officer for the state of New York.

Initially, the strategy was a winner for Scholing. Although it was nothing near their initial goal, he and his lawyer got an award of $9,000 from an Ulster County jury when the case was heard in the fall of 1922.

This victory unraveled within months, however. First, O’Connor’s attorneys successfully appealed the verdict and won a new trial. Then, almost exactly a year after the first trial, a second jury listened as the evidence was re-examined exhaustively and, perhaps, exhaustingly. “Scholing Is Stricken In Court,” one headline noted over a story describing how Kuni’s widower suffered a nervous collapse on the day the second trial opened.

Maybe Scholing could already sense the tide was turning. In any event, the second verdict cleared O’Connor, setting aside the $9,000 judgment. And, despite a series of furious motions and affidavits from Scholing’s attorney, this second result appears to have held. Kuni’s widower would get no more satisfaction from the courts in Ulster County.

Kuni’s death and her widower’s court fight illustrate both the dangers of a newly mobile age, and the chanciness of redress in the insurance-optional era. Had the Packard’s owner been insolvent, Scholing probably would have been advised not to bother seeking redress at all. And, as the story of his Ulster County lawsuit illustrates, a court action did not guarantee satisfaction, either.

One answer to this worrisome mix of rising injuries and uncertain outcomes was the limited-compulsory approach to liability insurance, a tack tried in Connecticut as early as 1925. By 1929, New York state followed suit with a law providing that a driver’s license and registration be suspended if the driver was convicted of certain serious driving offenses, or if the driver failed to pay a judgment resulting from a serious accident. The license and registration would be regained only if the driver could furnish proof he could pay a specified minimum for bodily injuries and property damages caused in a future accident.

The insurance industry remained leery of compulsory auto insurance for a long while, amid fears of politicized ratemaking, restricted discretion in underwriting practices and a higher potential for inflated or outright false claims.

The aim was to minimize the number of reckless and financially shaky drivers on the roads, but drawbacks soon emerged. “The basic fallacy was that the unsafe or irresponsible [drivers] could be identified by specified past events,” as one study puts it. A major flaw was requiring proof of financial solvency only after a driver had already failed to pay up in court. For who would bother suing a broke driver in the first place? By their own behaviors, truly reckless and insolvent drivers effectively put themselves beyond the reach of the limited-compulsory approach.

Massachusetts introduced the first completely compulsory auto insurance legislation in 1927. But the limited-compulsory, proof-of-financial-responsibility approach remained the norm in most states for the next several decades, adjusted from time to time but never entirely abandoned. The insurance industry remained leery of compulsory auto insurance for a long while, amid fears of politicized ratemaking, restricted discretion in underwriting practices and a higher potential for inflated or outright false claims.

But pressure for a more sweeping approach to what a 1968 survey called the “serious social problem” posed by auto-accident casualties eventually evolved into a nationwide trend, especially since New York (in 1956) and North Carolina (in 1957) by then had adopted their own compulsory insurance laws. Today, becoming the proud owner of one’s first car is inextricably entwined with attaining one’s first proof-of-insurance card. (Only New Hampshire continues to provide the option of proving financial solvency as an alternative to carrying auto insurance.)

No driver today hits the road serenely anticipating an accident. But it’s safe to say we travel secure in the knowledge that if we are unlucky, a firm structure of procedures will kick in to guide us, with insurance coverage a major player.

By contrast, my great-aunt Kuni’s long-ago roadside disaster took place in an era whose lack of signposts — both literal and legal — is almost impossible to fathom in a modern world where automobile travel is more regulated, more closely studied and certainly more insured.

Sources:

Helm, Robert E. “Motor Vehicle Liability Insurance: A Brief History.” St. John’s Law Review 43, no. 1 (1968): 25-56.

Michelbacher, G.F. “Casualty Insurance for Automobile Owners.” Proceedings of the Casualty Actuarial Society V, no. 12, (1918-1919) pp. 213-242.

Nerlove, S.H., and W.J. Graham. “The Trend of Personal Automobile Accidents.” The Journal of Business of the University of Chicago 1, no. 2 (1928): 174-201.

Norton, Peter D. “Street Rivals: Jaywalking and the Invention of Motor Age Street.” Technology and Culture 48 (2007): 331-59.

“Scholing Is Stricken In Court.” Daily Freeman (Kingston, N.Y.), October 9, 1923.

Watts, Linda S., Alice L. George, and Scott Beekman. A Social History of the United States. Vol. 3. ABC-CLIO, 2008. 78-79.

William Scholing, as Administrator, Etc., Plaintiff, against Charles R. O’Connor, et al, Defendants. Supreme Court: Ulster County (N.Y.). 24 Mar. 1923.

Liz Haigney Lynch is a genealogist, editor and writer whose work has appeared in the Miami Herald, the Sun-Sentinel of Fort Lauderdale, and the Chicago Sun-Times.