What would you say if I told you that a way to improve the profitability of an insurance company is to write new business that is materially underpriced? Sounds unlikely, right?

Have you ever been in a meeting where you heard something that sounded borderline outlandish and immediately spoke up and declared that the previous assertion couldn’t possibly be right? Well, I did, and I was wrong!

The assertion was that our company could afford to write new personal lines auto business at a combined ratio of over 120% and still improve our results. As a point of reference, most insurance companies generally target a combined ratio of 96%-97% for personal lines auto, so the idea that an insurer could pay out 20% more than they take in on new business and still come out ahead seemed far-fetched. I understood that additional risks meant that fixed costs could be spread over a larger base, which would allow an insurer to write at a loss, but a 120% combined ratio on each additional policy? That couldn’t possibly be! But it could!

How could this possibly be correct? How could an unprofitable company write new business that is even more unprofitable than the existing book and have the net impact of writing this even more underpriced business be an improvement to the bottom line?! Hold on to your hats because that is exactly what will be demonstrated below!

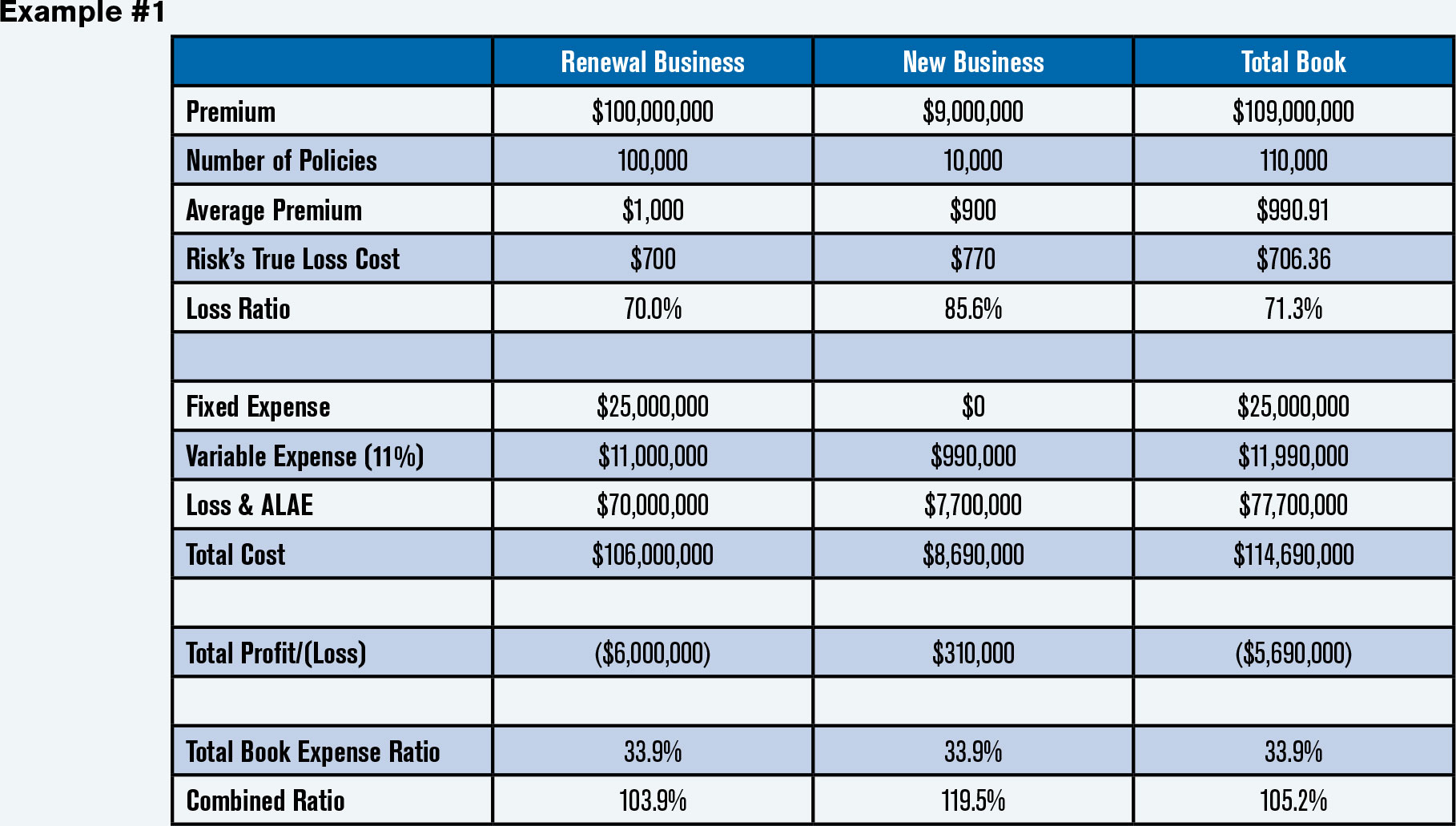

Two hypothetical examples are offered to illustrate how unprofitable business (i.e., BAD) plus new business which is even more underpriced (WORSE) can lead to a net gain (BETTER) — the heart of the Insurance New Business Paradox. Example 1 provides a detailed breakout of a hypothetical new and renewal book. The existing book consists of 100,000 policies and those policies are charged an average premium of $1,000 each. On average, the expected loss of the existing book is $700 per policy. The 10,000 new business policies have a true underlying loss potential 10% higher than the renewal book (so $770 in loss per policy). Even though the new business has a higher loss potential, the new business is charged 10% less to get them to switch to our hypothetical carrier (so a $900 premium per policy). In summary, the existing book has a 70% loss ratio and the new business has a significantly worse 85.6% loss ratio.

Premium covers loss and variable expense, as well as helps to cover a share of the company’s fixed expense.

Total book expense ratio assumed to apply for both new and renewal business.

Result of charging 10% less on new risks that are 10% Worse — NET OVERALL IMPROVEMENT

… most insurance companies generally target a combined ratio of 96%-97% for personal lines auto, so the idea that an insurer could pay out 20% more than they take in on new business and still come out ahead seemed far-fetched.

Despite the fact that more severely underpriced business has been added, the hypothetical carrier does indeed come out ahead. The existing book by itself generates a $6,000,000 loss, but the addition of the new business improved the profit by $310,000! What trickery is at work here you ask? The reason for this counter-intuitive result is that the new business will add value to the enterprise, so long as the new business has a loss ratio less than one minus the variable expense ratio. Said another way, if new business premium exceeds the associated loss and variable expense, it can pitch in and help shoulder the burden of the fixed cost, thereby adding value.

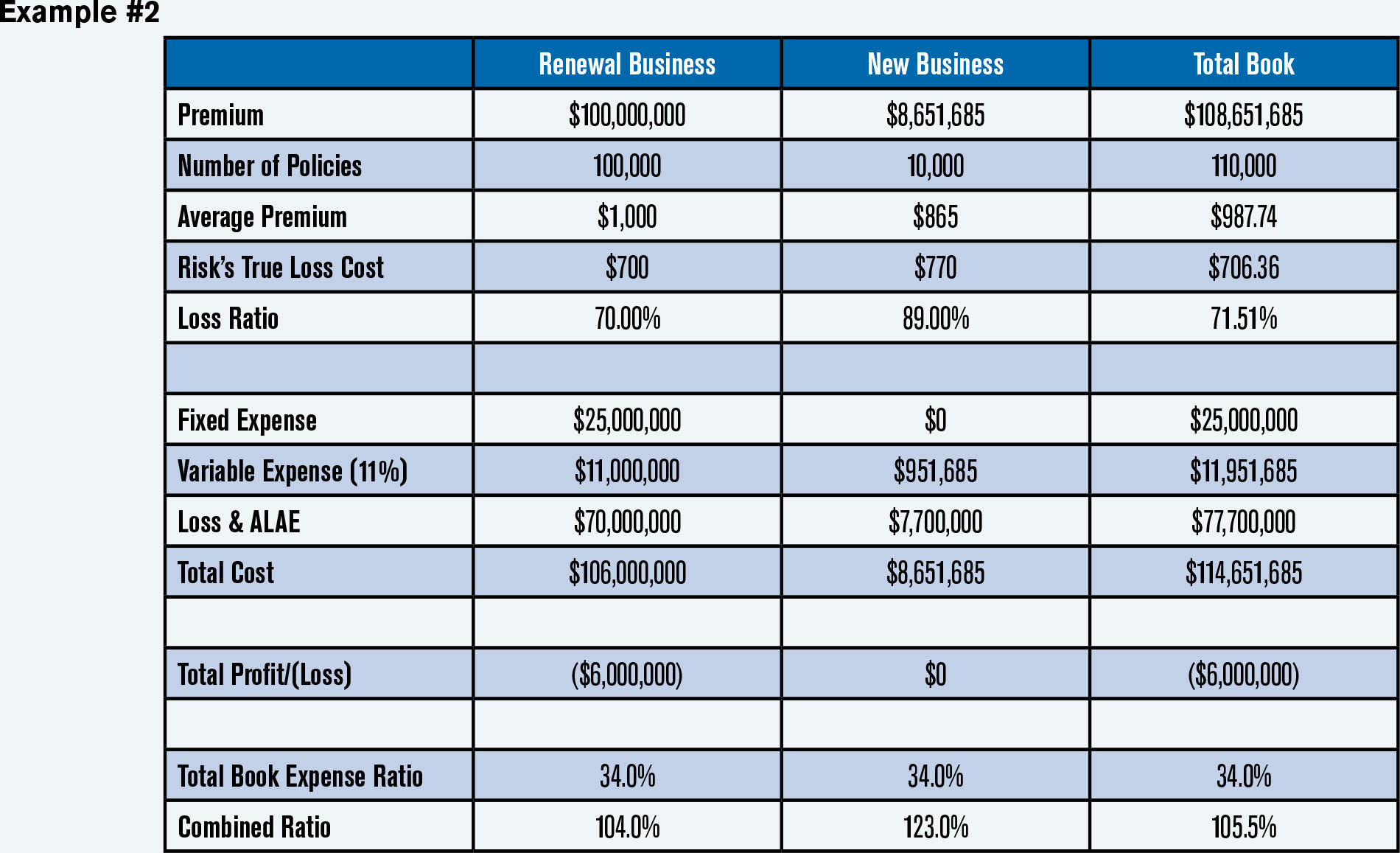

Example 2 shows a detailed breakout of the same hypothetical new and renewal book. However, this time, the new business premium is set such that the loss ratio would be equal to one minus the variable expense ratio. This means the new business is now exactly covering its costs and is neither adding nor subtracting value — the break-even point.

No premium remains to help carry the burden of the fixed expense.

Total book expense ratio assumes to apply to both new and renewal business.

Result is that new business loss ratio equals one minus variable expense ratio – BREAKEVEN

Shown at the bottom of Examples 1 and 2 is the combined ratios for the new and renewal business. In Example 1, a new business combined ratio of less than 123% would add value to the enterprise.

For some of you reading this article, this will be new information. For others, you’ve seen this before. The real lesson in all of this is to always, always, always withhold judgement. No matter how ridiculous something sounds in a meeting — withhold skepticism. Counter-intuitive does not equal wrong. Bite your tongue, go back and do the necessary homework and then after careful consideration share your results with others. If only I could have taken my own advice!

Rob Kahn, FCAS, is a pricing manager for Horace Mann Insurance and a member of the Actuarial Review Working Group