Explore the growing impact of third-party litigation financing on insurance claims, reserving practices, and pricing strategies.

In seeking out the roots of the social inflation problem, P&C insurers have landed on a stealthy cause: third-party litigation financing (TPLF).

TPLF is a financial arrangement. Simply put, it is an investment in a lawsuit. An investor provides funding for a legal claim in exchange for a share of the potential settlement or judgment. Litigants can pursue cases without bearing the full cost upfront.

Insurance companies complain that the financing skews the playing field against them. Plaintiffs can tap the financiers’ deep pockets to bring in a larger settlement.

TPLF is “the jet fuel funding megaverdicts,” Alan Dobbins, director of research at Conning, an investment management firm that serves the insurance industry, told a webinar audience on February 11.

More than anything else, insurers hate the stealthy nature of litigation financing. In most cases, there’s no requirement to disclose a funding agreement. Players across the industry have banded together in what seems to be their top priority: requiring plaintiffs to reveal the presence of TPLF in a case.

The financiers respond that they are leveling out a field that had been skewed for decades in favor of insurance companies and the defendants they protect. They see themselves as supplying rocks to a David-and-Goliath struggle.

This article will give the history of financing lawsuits, document the recent growth of TPLF, and describe how insurers are seeking solutions in the courtroom and the legislature. It will also describe how insurance companies are trying to ferret out the presence of TPLF and minimize its impact on their portfolio.

History of TPLF

Litigation funding is an attractive asset class. Most financiers are private, so all industrywide data trends should carry an asterisk, but returns can exceed 20% on invested capital. Results are uncorrelated with traditional investments like stocks and bonds.

And the asset class is growing, perhaps doubling in size from 2017 to 2021, according to a U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) report.

In the U.S., litigation financing was virtually unheard of until about 10 years ago. In many states, it was illegal.

The practice can sometimes be compared to a legal skullduggery known as champerty. That practice can be traced back to ancient Greece, but it became notorious in England during the Middle Ages, an era in which the king was not much more powerful than the aristocracy that was nominally subservient to him. Government courts could be intimidated, especially in the hinterlands, by barons who could overrun a weaker neighbor through their wealth and power, as Edmond H. Bodkin noted in his 1935 book, “The Law of Maintenance and Champerty.”

If the weaker neighbor went to court, Bodkin wrote, “he found the law powerless to aid him.” Before the cowed judge, the influence “of the name of one of the great lords … [would] carry the day.” If that wasn’t enough, a bribe did the trick.

Investing in the case became known as champerty, and perpetuation of the case became known as maintenance. You’ll usually see these two terms together: champerty and maintenance, a slight anachronism held together by linguistic momentum, like stock and trade or hither and yon.

The practice was ubiquitous in the 14th century. Even Alice Perrers, mistress of Edward III, had to be cajoled out of it.

Eventually, according to “History of Conspiracy and Abuse of the Legal System,” a 1921 overview, the Tudor monarchs gained enough power that they (and the English courts) could cow the gentry. (The Star Chamber helped.)

The practice remained suspect, though for new reasons: distrust of lawsuits and lawyers. As a 2019 article in the Third-Party Litigation Funding Review put it, “Litigation itself was a vice to be avoided.”

That was the attitude when the U.S. gained independence. States generally adopted the British common law restrictions against champerty and maintenance.

Over time, though, the taint hanging over the practice dissipated.

What changed? The Massachusetts Supreme Court summed it up in Saladine v. Righellis (1997), which overturned the state’s champerty ban. The court agreed with an American Bar Association report that lawsuits had shifted from being “a social ill, which like other disputes and quarrels, should be minimized” to “a socially useful way to resolve disputes.”

The U.K. and Australia did away with champerty and maintenance as criminal or civil wrongs, the former in the 1960s and the latter in the 1990s.

In the U.S., an active debate remains. As a 2020 New York City Bar report noted, 28 states permit maintenance to some degree, and 16 explicitly allow champerty.

“However,” the report noted, “other states have refused to abandon the champerty doctrine simply because a few states have chosen to do so.”

But the social opprobrium has eased. Burford Capital, a leader in the field, claims that it has received queries from 94 of the 100 largest U.S. law firms by revenue and from 92 of the 100 largest global firms.

Thanks to the legal and ethical ambivalence, funders structure their agreements carefully. Many explicitly disclaim any right to control litigation strategy while maintaining access to nonprivileged case information for monitoring purposes. The industry’s adherence to such frameworks has helped it gain legitimacy in jurisdictions where champerty remains an unsettled issue.

Whether the practice is a social good is subject to debate. In its 2022 study, the U.S. GAO gave a reasonable listing of the pros and cons:

Pros

- TPLF levels the playing field for underfunded plaintiffs. A small company might not pursue a strong case against a large corporation without more financial resources.

- It allows plaintiffs to “convert the value of their claims to cash.” They won’t have to wait until they win a case and the entire appeal process, which can take years.

- It lets plaintiffs shift the risk of a negative outcome to the financiers. Plaintiffs won’t be stuck with legal costs if they lose. This, the GAO said, is similar to the way insurance companies relieve policyholders of risk.

- The due diligence the financiers undertake can give plaintiffs insight into their own cases.

- The accounting treatment of TPLF lets corporate plaintiffs take litigation costs off their balance sheet.

Cons

- TPLF is expensive. We’ll discuss how expensive in a moment. The financiers say they take great risks, which deserves great reward.

- It may slow down settlements. Plaintiffs might reject a fair settlement to get back the money the funding organization will receive.

- It could increase defense costs. Delays in settlement inevitably drive settlement amounts higher, and the longer a case lasts, the more legal costs the defense incurs.

- A financier could explicitly or tacitly control the litigation, leaving the actual plaintiff unable to settle.

- If the plaintiff’s attorney is the borrower, they could find their own interests in conflict with those of their client.

How TPLF works

Some observers liken litigation finance to buying stock. However, it’s really closer to banking.

Stripped down, TPLF is a nonrecourse loan; the future settlement is collateral. If there is no settlement, the borrower defaults, and the financier has no collateral to collect.

There are two types of litigation finance. Personal TPLF, where firms front relatively small amounts, typically tens of thousands of dollars, to individuals in exchange for a piece of a future settlement of, say, a personal auto settlement or a health insurance claim. Insurance industry advocates don’t focus here much.

Insurers worry more about commercial TPLF. It is there, they say, that financing is ratcheting up payouts.

Unlike banking, TPLF is lightly regulated. The GAO report noted TPLF isn’t specifically regulated under federal law. State laws tend to focus on interest rates and other consumer protections.

Most commercial TPLF deals are in the millions of dollars, sometimes in the tens of millions. Payouts can be enormous. Burford Capital funded a $16 billion dollar victory in litigation over the nationalization of the Argentinian oil producer YPF. The judgment is on appeal. According to the company’s 2024 Annual Report, Burford had invested $70 million and already won triple that. It has put a fair value of $1.5 billion on its share of the overall deal.

On the smaller side was Burford’s deal with jalapeño farmer Craig Underwood. Underwood received $4 million to finance his appeal after winning a suit against the makers of Sriracha hot sauce. When his case settled, he happily paid back the $4 million — plus another $4 million.

“They stepped in and helped us out when we couldn’t get help from anybody else,” Underwood told journalist Lesley Stahl in a “60 Minutes” segment on TPLF in 2022. “They basically rescued us.”

A more typical TPLF client, though, is a law firm. The financier will sometimes fund a single case or sometimes lend against several cases brought by a single firm. The diversification smooths cash flow for both organizations.

Insurance-related matters are only one facet of TPLF and, by most accounts, not the largest. Burford, for example, invests in patent disputes and antitrust and arbitration matters, as well as the commercial litigation matters that insurers are most focused on.

Financiers enjoy hefty returns. In a 2022 study, Swiss Re reported that litigation funding firms posted internal rates of return of more than 20% for personal injury, commercial litigation, and mass tort in each of the previous three years.

Returns of 100%, like Burford got from farmer Underwood, are routine, “singles and doubles” in the words of Burford chief investment officer Jonathan Molot.1 About 60% of deployed capital since the firm’s inception has returned between zero and 99%.

Then there are the “home runs.” They represent only 16% of capital, but they generate 30% of returns.

There can be strikeouts, too — 14% of invested capital has posted a negative return. So far, though, Burford’s wagers have been as likely to return over 200% as to lose so much as a dollar.

Their results are favorably skewed.

“When we lose,” Molot told investors, “we can’t lose any more than we invest. But when we win, we can win many times more than we invest. It’s a beautiful thing.”

It’s the opposite skewness of an insurance portfolio, where profits are limited to premium plus investment income less expenses but losses are virtually limitless.

Overall, at the end of 2024, Burford’s weighted average return on invested capital was 87%, with an internal rate of return of 26%.

It costs money to underwrite and decline business, and these numbers don’t seem to be captured in those returns. Burford turns down a lot of opportunities. It takes on only about 5% of the deals it sees. Burford claimed an average return on tangible common equity of 14% from 2022 to 2024.

And the firm is growing fast, showing a 15% compounded annual growth rate from 2020 to 2024.

There’s a lot there that rankles insurers.

Stef Zielezienski, chief legal officer at the American Property Casualty Insurance Association (APCIA), takes the most philosophical argument. Litigation funding, he said, is “outside parties investing in the outcome of a branch of government.” It makes government into “a competitive, profit-seeking market … [which] … introduces all sorts of dysfunction. What is justice? Is justice getting the most profit out of a lawsuit? Justice is making sure the injured party has a remedy.”

Dale Porfilio, FCAS, formerly of Triple-I and now of WTW, points out that the fat returns poke holes into the social justice/David-and-Goliath argument.2 “If you’re doing this [as a favor] for the plaintiff, then why do you need such a high yield?”’

The fat margins might leave less for the successful plaintiff. A typical case involves negotiations within a narrow range — 10% to 15% of a central estimate, said Dan Costello, managing partner of the defense firm of Costello, Ginex, and Wideikis. To post the margins they claim, financiers would be reducing the plaintiff’s share.

Indeed, Swiss Re estimated that settlements with TPLF would have to be 27% higher, on average, for the plaintiff to be better off.

Higher settlements, of course, raise loss costs, which ultimately raise the price of insurance. Costello has seen the explosion in megaclaims. Five years ago, he had never seen a demand over $100 million. Last year he saw five, including one over $250 million.

A 2024 RAND study found that between 2010 and 2019, trial awards per plaintiff grew at an annual compound rate of 7.6%, even after adjusting for inflation.

Milliman examined 60,000 hospital professional liability claims through 2023. Over the last five years the percentage of claims above $5 million is more than 400% higher than those from a decade earlier. Claims take longer to settle, too. Milliman found that the time from report to closure was 27% longer in 2024 than the 2017–2021 average.

The megaverdicts increase claim variability by flattening the tail of the distribution. That nudges insurance prices higher, too, either as a direct risk load or because insurers must sacrifice investment income to have enough current assets to cover potential megaverdicts.

The result: higher premiums. Ultimately, insurers say, the consumer bears the cost.

Insurance inflation can’t be attributed solely to TPLF. Insurers also point to societal attitudes, erosion of tort reform, attorney advertising, and courtroom strategies.

These and similar phenomena are considered drivers of “legal system abuse,” the term much of the industry has adopted instead of “social inflation.”

“I think this is the biggest issue affecting the industry,” said FCAS Brian Brown, a principal at Milliman.

Insurance industry response

Insurers might not like TPLF, but they acknowledge it won’t go away.

Instead, they want to know when a plaintiff has received funding. That will help them develop a more effective strategy — whether to defend or settle and for how much to settle.

Right now, funding is rarely disclosed. When it is disclosed, sometimes only the judge finds out to ensure they don’t have a conflict with the funding organization.

The insurance industry wants full disclosure. Zielezienski of the APCIA puts it simply: “Everybody should know.”

Getting that to happen is a battle on many fronts. Federal and state courts make their own rules. That’s more than 50 fronts. The courts’ rules can be superseded by laws passed by federal or state legislatures. That’s another 50-plus.

At the federal level, Rep. Darrell Issa introduced the Litigation Transparency Act of 2025 on Feb 7 (H.R. 1109). He has done this more or less annually going back to 2021.

As to the federal courts, the U.S. Supreme Court’s Advisory Committee on Civil Rules agreed in October to create a subcommittee to look at disclosure. “It probably deserves a careful look, if for no other reason than we don’t know what we don’t know,” U.S. District Judge David Proctor said in an article in “The American Lawyer.”

Cheering all this on are more than 100 large companies, including Amazon, Google, Johnson & Johnson, ExxonMobil, and Ford Motor, all of which favor full disclosure, joining the classic insurance trade groups, RIMS, Lawyers for Civil Justice, American Tort Reform Association, Institute for Legal Reform and the National Federation of Independent Businesses.

At the state level, at least 35 bills regulating litigation funding were filed in the first four months of this year, according to Insurance Insider, a trade publication — 25 more than a year ago. Many required disclosure of funding agreements.

Kansas enacted Senate Bill 54, which requires disclosure of the parties in the funding agreement and whether the funder has any control over whether the claim can settle.

Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp signed Senate Bill 69 in April. It requires the disclosure of the existence, terms, and conditions of funding agreements for payouts more than $25,000.

These states join Wisconsin, West Virginia, and Montana in having disclosure requirements. The oldest of these is Wisconsin’s law, passed in 2018.

Insurance representatives say it is too early to determine whether any of the laws have had an impact. The laws are recent, and the states passing them are relatively small. Over time, insurers hope to build a dataset and predictive models that show how litigation financing affects a case.

At least one litigation financier has a dataset and predictive models (see text box on p. 32).

Current tactics

Changing laws and courtroom rules might happen one day. What are companies doing today?

First, they try to learn if any of the claims they are handling are being financed. That’s not easy; remember, the TPLF agreement is rarely disclosed. The case can open, be argued, and settle, and the insurer will never know if it was funded.

There are clues, though.

Maybe one day, the defense counsel starts noticing “a bigger army of experts than you normally see,” said Matthew Morrison, a vice president for litigation for American Family Insurance Group. Sometimes there are two or three experts in the same field or more subspecialists.

“Experts to the max,” he said.

Or maybe an injured person is getting a significant amount of treatment outside of network, said Costello, the managing partner at Costello, Ginex, and Wideikis. He saw a recent case with $1 million in out-of-network treatment.

Or you’re on the defense side of a claim that feels like it’s a longshot for the other side. Costello handled an early case around Illinois’ Biometric Information Privacy Act. The funding organization “took a flier on it.” The first lawsuits were small — suing a tanning salon that required fingerprint identification. Then, they grew to monumental proportions, such as suing Six Flags and Facebook.

Or maybe there’s an exorbitant ask, looking for more than $10 million plus. That used to be a red flag, Costello said, “but any more it gets so that all the cases are way out there.”

Morrison and Costello are active in the CLM, a group for claims professionals. It has organized a subcommittee that looks at issues like TPLF and nuclear verdicts.

Megasettlements and any sort of inflation affect reserving work, noted William Finn, FCAS, senior vice president and chief actuary and data officer at Hanover Insurance.

The Consumer Price Index spike around 2021, the pandemic, and social inflation trends like TPLF have “disrupted” most companies’ loss triangles and the loss development methodologies that depend on them, Finn said.

He suggested looking at the volume of outstanding claims and metrics like case reserve plus IBNR per claim. Those need to seem reasonable in light of recent trends.

Instead of using traditional loss development and backing frequency and severity statistics out from that, Finn suggested flipping the script — developing frequency and severity first, making sure the implied inflation is appropriate, and using that information to develop ultimates.

There are proactive approaches, too, in terms of underwriting and pricing.

Finn noted companies could proceed cautiously in hot spots, areas where more cases are filed — the proverbial judicial hellholes.

He recommended that actuaries avoid “soft-pedaling our trend assumptions.” Trends from 8% to 12% annually might be normal.

Brown, the Milliman actuary, noted companies could write lower limits. Some companies have left TPLF heavy lines of business like commercial auto and hospital professional liability. And of course, actuaries can use their data skills to tease out where problems lie.

Porfilio said some actuaries have shown data on social inflation trends in their rate analyses. They might not select those trends, but their presence shows “there is a pressure going on beyond old school economic trends.”

In the meantime, TPLF continues to shape the legal landscape insurers traverse. They will have to continue to adapt to the changing courtroom as it is changing while developing ways to detect and harness it.

Sidebar: Deep Data and Modeling Drive Litigation Success

With no disclosure requirement on litigation financiers, insurers have no realistic way to get information about what cases attract the capital or how those cases turn out.

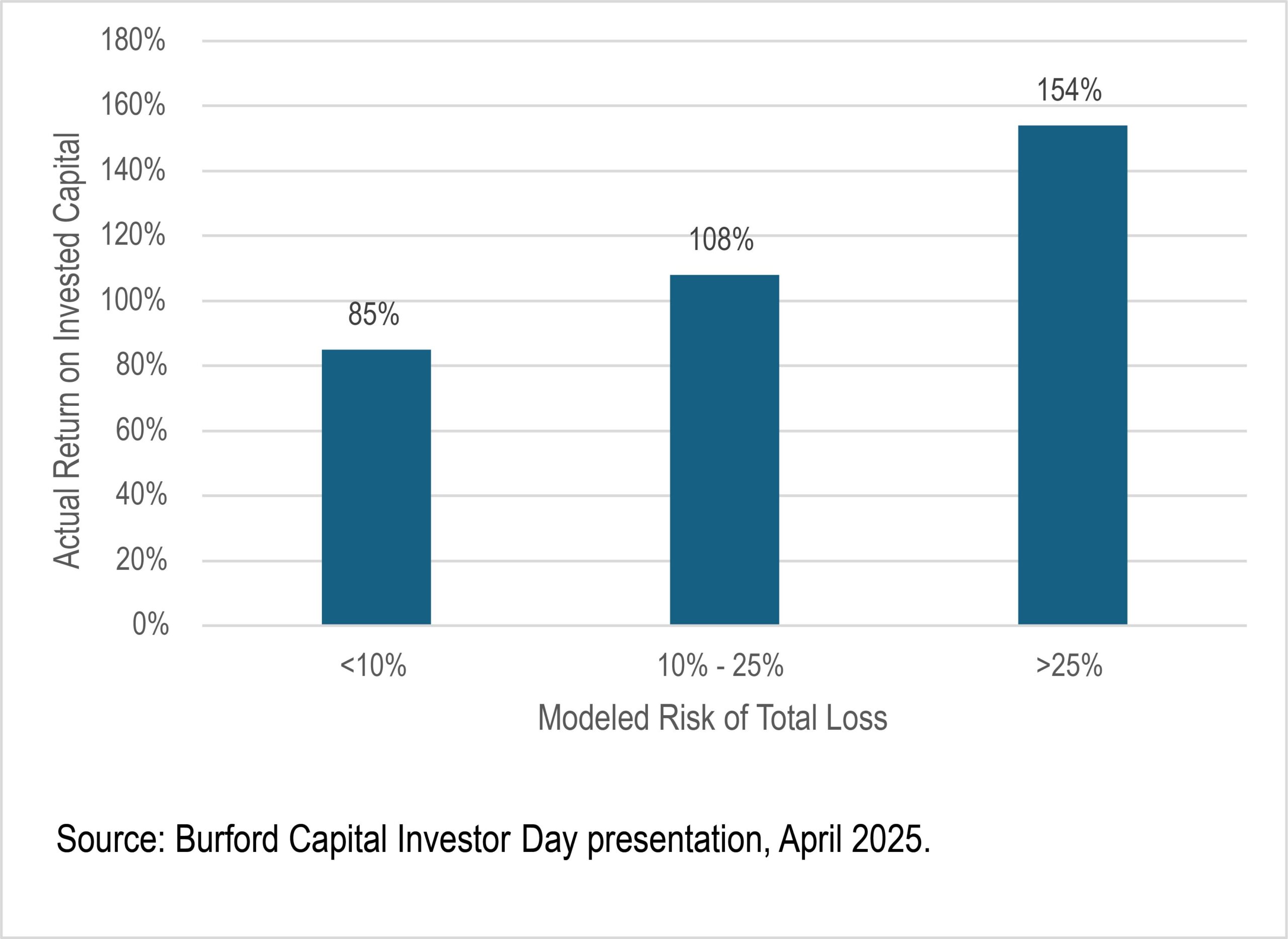

Burford Capital shows how important that information can be. At Burford’s Investor Day in April 2025, chief investment officer Jonathan Molot outlined how quantitative modeling drives the firm’s success. Burford leans on quantitative models to choose its caseload.

Burford’s investment process relies on a dual-layered analysis, beginning with a traditional legal review. Experienced underwriters conduct a “merits-based” analysis. They look at the facts, the relevant law, the jurisdiction involved, and other considerations.

“But that’s not enough,” he said.

Their quantitative models tap data from their own settlements — thousands of commercial cases over the past 15 years. Burford supplements publicly available information.

Public litigation data is often skewed by small commercial cases and personal injury claims, information irrelevant to Burford’s portfolio, Molot said. And it shows only adjudicated cases, not out-of-court settlements.

In addition to adjudicated cases, Burford’s dataset has data for cases that settle before adjudication and data on settlements negotiated after adjudication. These yield insights that competitors cannot get, Molot said.

Their data lets them pick up on trends. For example, settlements have taken a bigger share of Burford’s case proceeds in recent years. Through mid-2021, 41% of proceeds came from settlements. Since then, 79% have.

The shift may come from pandemic-related court congestion, Molot said. Judges have encouraged settlements to reduce case backlogs. Another possible reason: Fortune 100 companies are leaning on litigation finance more often. The financing, added to their size, can intimidate their courtroom opponents, creating an incentive to settle.

Burford builds a unique model for every case it invests in, Molot said. After the qualitative-heavy underwriting and the quantitative-heavy modeling, cases are reviewed and approved by a commitments committee.

“We price to risk,” Molot said, “and we are very good at it.”

The models continue to play a role as the case proceeds, he said. They also inform Burford’s portfolio management, balance sheet and cash flow planning.

The models show the classic balance between risk and reward. As the chart shows, cases return on average 85% on invested capital when models predict the chance of a total loss is less than 10%. Cases average returns of 154% when the risk of total loss exceeds 25%.

At the end of 2024, Burford’s weighted average return on invested capital was 87%, with an internal rate of return of 26%.

Jim Lynch, FCAS, MAAA, is retired from his position as chief actuary at Triple-I and has his own consulting firm.

[1] We don’t know how long Burford’s capital was tied up in Underwood’s case, so we can’t calculate an IRR to compare to the Swiss Re numbers.

[2] I retired from the Insurance Information Institute in 2021 and still do occasional consulting work for them. Porfilio and I have written and spoken in public several times on social inflation and related issues. I have always focused on documenting the presence of social inflation and left to Porfilio and others the task of divining its causes, including TPLF.