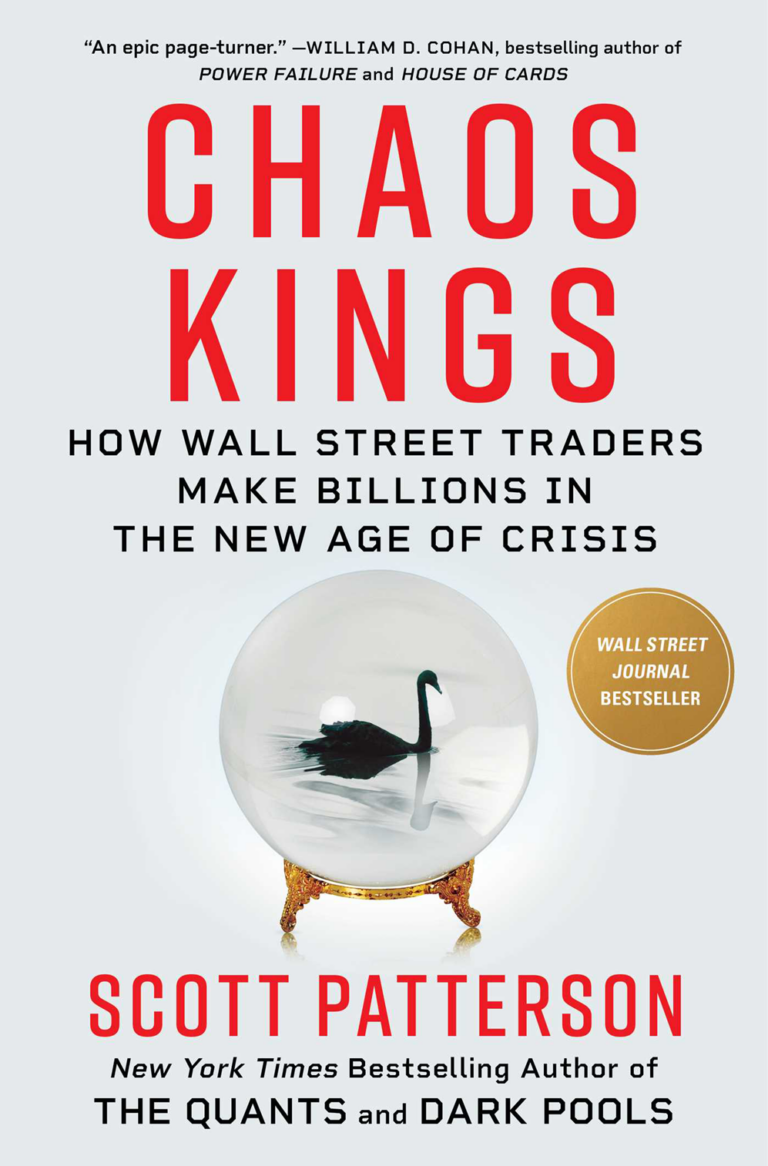

Chaos Kings by Scott Patterson, Scribner 2023, $15.00

For an insurance professional, Chaos Kings is thought-provoking until its narrative hits a brick wall.

Author Scott Patterson, a veteran reporter for The Wall Street Journal and a New York Times best-selling author, profiles the quants who find profit in financial calamity.

Chaos Kings purports to explore the dark regions where quants “turn extreme events into financial windfalls.” And what is insurance but a dark region where actuaries turn extreme events into, if not windfalls, steady income streams?

I thought I’d be reading how Wall Street profits from apocalypses: earthquakes, wildfires and hurricanes. Patterson instead focuses on metaphorical quakes, fires and ‘canes. When financial markets plunge — for whatever reason — characters in this book can make millions.

How do they do it? The narrative, at first, pits competing visions.

On one side are a team: derivative trader Mark Spitznagel and theorist Nassim Nicholas Taleb. Spitznagel learned in the pits of the Chicago Board of Trade that one big score can offset dozens or hundreds of tiny losses. Taleb popularized the idea of black swans — extraordinary events that can’t be predicted precisely but that affect markets in predictable ways.

Their life lessons drive their financial strategy. They purchase extraordinarily cheap stock options, usually puts, whose values rise when the value of their underlying security falls. The options are cheap because markets underprice the likelihood of disaster.

When the market is wrong Spitznagel and Taleb benefit. At the outset of the global financial crisis in 2008, while the S&P 500 fell 37%, their Universa hedge fund made $1 billion.

Their opposite is Didier Sornette, a French mathematician who noticed that the pattern of stock prices in the late 1990s resembled the signals certain pressure tanks throw off as they approach failure. It was a universal failure signal, he concluded, and so he successfully predicted the bursting of the dot-com bubble in 1999.

Success sent Sornette on a modeling quest. He sought Dragon Kings — rare, catastrophic market events that, given enough information, could be predicted.

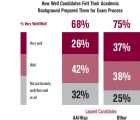

The parallels to actuarial science are obvious. Author Patterson sees them but oversimplifies. “Insurers, who can diversify risk across many independent events, worry only about the expected loss,” he writes. “But when there’s no one able to provide insurance … then you absolutely must … add a risk premium.”

Like Sornette, we seek models that pinpoint where calamity awaits. We worry about the tail of the distribution. And we do add a risk premium, where one is allowed and appropriate.

Unlike Sornette, we understand at a deeper level the changing nature of risk. Insurance history teems with risks that weren’t anticipated but were covered. Asbestos losses were an expensive example; ransomware a recent one. Using Sornette’s imagery, today’s Dragon King was a salamander not long ago. How do you model that?

Actuaries know a good model can explain a lot, but it can’t explain everything. If it did, it wouldn’t be a model. It would be reality.

Author Patterson might realize the futility of Sornette’s approach. He refocuses on Spitznagel and Taleb and their hedging. It’s a good call from a veteran financial writer. Patterson worked at The Wall Street Journal and wrote a bestseller, The Quants, about the rise of mathematical traders.

The author sketches his characters enough to keep them interesting. Sornette motorcycles L.A. freeways at 175 mph.

Spitznagel snowboards deep powder and guides gliders above mountains. But he is a patient trader, absorbing years of tiny losses before calamity triggers a payoff.

The parallels to actuarial science are obvious. Author Patterson sees them but oversimplifies.

Taleb goes swan crazy. After the 2008 market crash the term “black swan” becomes a buzzword. Taleb embraces his celebrity and starts to see threatening swans everywhere: black ones, white ones, gray ones.

The true foe of Spitznagel and Taleb is modern portfolio theory, the investing philosophy that suggests diversifying investments at, say, 60% stocks and 40% bonds, will maximize gains while minimizing risk. Spitznagel and Taleb would recommend an off-kilter bar-belling of extremes. They counsel something like 97% in stocks and put 3% in their Universa fund, with its strategy of buying way-out-of-the-money puts for the rainiest of days.

The 97% strategy means you’ll make more in a typical year because stocks generally outperform bonds. The 3% hedge protects you in years roiled by bursting bubbles or pandemic panics.

It’s worth noting (Patterson doesn’t): The strategy doesn’t eliminate risk. It shifts it. If markets tank, can the folks who sold you those cheap puts pay what they owe? Counterparty risk drove the 2008 financial crisis. Owners of mortgage securities had hedged their risks. When the securities faltered, the counterparties couldn’t pay.

It’s all good fun reading, until that brick wall. Two-thirds of the way into the book, dragons and swans yield to an exploration of the risk of climate change. It’s certainly an important issue, but the risk has been reasonably well modeled. The initial forecasts, 30 years on, have held up. Climate change is a problem of politics, not math or science.

For the rest of the book, the author flails as anyone might after a brick-wall encounter. He conflates the Jan. 6 insurrection; the collapse of Texas’ electrical grid; water-treatment problems in Jackson, Mississippi; wildfires near Mount Rainier; and Hurricane Ida to suggest a world gone out of control. He glosses over solutions — parametric insurance grounded in the blockchain; gray swan research by Aon; a Lloyd’s of London project.

The book feels slapdash as it concludes. The narrative drive and tension that made it fun are gone. It fails to show a coherent approach to the cataclysms of the 2020s.

But perhaps that is the author’s ultimate point.

Jim Lynch, FCAS, MAAA, is retired from his position as chief actuary at Triple-I and has his own consulting firm.