The 2025 Spring Meeting in Toronto, Ontario closed out with a general session on “How Actuarial Science can Benefit from AI…and Vice Versa,” a panel discussion featuring three artificial intelligence (AI) experts — Frank Chang, Max Martinelli, and James Guszcza. The panelists provided their perspectives on how the actuarial profession will — or should — evolve in response to increasing usage of AI. Topics included the potential to streamline actuarial workflows by integrating new tools and the opportunity for actuaries to use their professional expertise to champion human-centered design of AI tools.

Changes to the actuarial role

Chang is a vice president of applied science at Uber and a former president of the Casualty Actuarial Society. He discussed the potential impact of AI on the actuarial profession on two axes: how much the role will evolve and how many actuarial roles will be needed in the future.

Chang began by presenting the argument that we are trending toward an “all robots” future, in which actuarial roles are replaced by AI. He recounted a story from his first job that involved manually entering data from 100 pages of paper into a spreadsheet. Today, a job like this could be done using optical character recognition and generative AI. Other tasks that could be automated using AI include creation of exhibits to support rate filings and data processing to support rate reviews.

AI could also play a role in analyzing the data. “[AI tools] could just pull out all the weird factors, all the things that are exceptional,” said Chang. “You don’t have to review all the cuts yourself. It can just pull up the cuts that you should look at.”

AI “agents” can also break down tasks and carry them out in sequence. “It’s pulling stuff from the web,” said Chang as he showed a video of an OpenAI agent in action. “It’s then using Python to graph it, to chart it, to make reasoning and judgment calls,” leading to a recommendation.

Chang counterbalanced this by presenting the case for an “all humans” future, describing limitations of AI that necessitate human supervision. AI can “hallucinate” nonsensical results — he pointed to an example in which the AI overview of a Google search recommended adding non-toxic glue to pizza sauce, to prevent cheese from sliding off a pizza.

Chang pointed to the complex legal and regulatory risk surrounding use of AI that would be mitigated by actuarial expertise in interpreting laws and regulations in the context of data and modeling. He recounted a story about a customer prompting a car dealership’s chatbot to commit to selling a 2024 Chevy Tahoe for $1 and to include a statement that it is a legally binding offer. In some cases, courts have upheld commitments made by AI chatbots.

Chang pointed to the complex legal and regulatory risk surrounding use of AI that would be mitigated by actuarial expertise in interpreting laws and regulations in the context of data and modeling. He recounted a story about a customer prompting a car dealership’s chatbot to commit to selling a 2024 Chevy Tahoe for $1 and to include a statement that it is a legally binding offer. In some cases, courts have upheld commitments made by AI chatbots.

Legal issues related to ownership of data are prevalent when AI is involved. Chang introduced the audience to “the pile,” a large open-source language modeling dataset created from sources such as academic articles, books, websites like Wikipedia, and YouTube subtitles. Use of the pile to train a model led to a lawsuit against the AI company Anthropic, based on the allegation that the data contained pirated books. (The books at issue have since been removed from the pile.) Ambiguity of ownership of some components of the pile further complicates the situation.

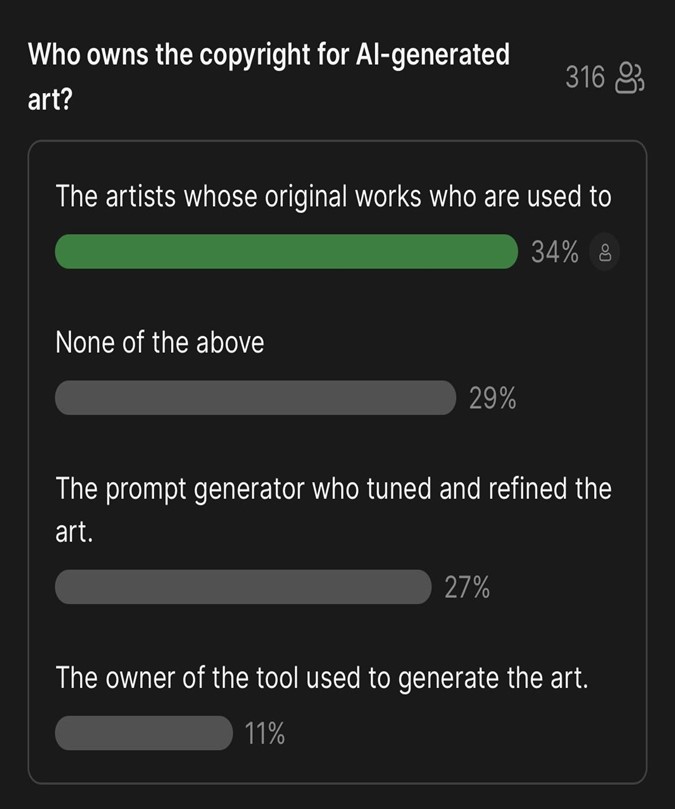

There is also ambiguity over ownership of the outputs of an AI model. Chang polled the audience for their view and found a mixed response, with a slight plurality of attendees having the view that copyright for AI-generated art belongs to the artists whose original works are used to train the model. (See figure below.) The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office has refused to grant copyright to AI-generated work, and a U.S. Appeals Court has rejected copyright for AI-generated work on the grounds that it lacks a human creator.

Chang closed by cautioning that lazy use of AI can result in low-quality results but pointed toward an opportunity for actuaries. “What actuaries could provide is judgment,” he said. “We can judge if something’s good or not good. That is really our secret sauce. Using that actuarial judgment, you can actually make AI a lot more powerful.”

Lessons from history

Martinelli is a lead actuarial data scientist at Akur8 and a close collaborator with the Casualty Actuarial Society, leading the CAS AI Fast Track Bootcamp and co-hosting the CAS Institute’s new AI podcast, “Almost Nowhere.” He drew on some lessons from history to explain three predictions for the future of AI.

Martinelli began by pointing out that, despite scientific advancement, industrialization, and computerization, fundamental aspects of the human experience have not changed. Thousands of years ago, “humans ate meals with their family and friends … they enjoyed song and dance, they engaged in trade and commerce,” he said. “Powerful things can happen and change the world around you very quickly, but the world can still look very familiar. Humans will still be humans.”

Martinelli emphasized that this doesn’t mean we should “do nothing,” but rather, we will need to continue to adapt and encouraged actuaries to become fluent in AI. “If you subscribe to the viewpoint that AI is a tool, we’ve been through this before.” Actuaries used to use tools like slide rules, Merchant calculators, and columnar pads and have adapted to new technologies as they became available.

When Excel brought new efficiencies to actuarial departments in the 1990s, the actuarial function wasn’t slashed. “The real value was in what we opened up,” said Martinelli. “The profession actually grew, and we started doing a lot more stuff, and it was more meaningful. It was deeper analysis.”

Despite these changes, actuaries are still concerned with the financial mathematics of risk just as they were 100 years ago. “If you think about what the role of the actuary is, it’s not really a task,” said Martinelli. “This idea of just understanding financial mathematics of risk looks really similar to 100 years ago. But the job looks unrecognizable.”

Martinelli drew on some lessons from military history to explain the importance of pairing a new technology with a shift in strategy. “Technologies, on their own, are rarely the thing that’s a big deal,” he said. “It’s kind of the strategy shift that makes them catalytic.”

Illustrating by example, Martinelli pointed out that the stirrup was invented long before the time of Genghis Khan. However, the strategic shift his army made was to use the stirrup to allow archers to stand and steady their aim while riding a horse. Historians point to this use of the technology as what allowed his army to be successful.

Martinelli closed by offering three predictions based on these observations:

- AI will deliver and disrupt.

- The world will still look familiar, and actuaries will still be the gold standard if we continue to adapt.

- There will be winners and losers, with the winners being determined by strategy changes.

Actuaries as proponents of human-centered AI

Guszcza is a principal at Clear Risk Analytics and was the first person to be designated as Deloitte’s U.S. chief data scientist. He explained the importance of designing AI systems in a way that allows them to be used effectively by humans and proposed that actuaries should have an expanded role in the design of these systems, going beyond the insurance industry.

Guszcza began by explaining that AI is an ideology as much as it is a technology. The way to view AI as a technology is the way that Chang presented it — that it is a tool that does specific things like automatically generating an R or Python script. The ideological aspects of AI come from the language that people use to talk about it.

“The way it’s discussed is that it’s going to become this kind of general-purpose intelligence that’s essentially going to put us all out of work,” said Guszcza. This ideology is embedded in the mission statements of some of the big AI players, which contain statements about AI being autonomous or outperforming humans.

Guszcza paraphrased author George Orwell as a caution to the audience: “Sloppy language makes it easy for us to have foolish thoughts.” He identified two problems with AI ideology. First, it creates the illusion that AI is “just one thing,” when it has already been around us for decades: in internet search, GPS navigation, autocomplete, and automatically generated subtitles. Second, it gives the wrong idea of how to think about AI — rather than viewing AI as a replacement for humans, Guszcza proposed that “we should really be thinking of AI as a component of a collective intelligence process.”

Guszcza explained the idea of a collective intelligence process by describing a “centaur chess” tournament, in which human players competed with the assistance of computers. The winning team consisted of two amateur chess players and three off-the-shelf chess programs, beating chess grand masters and the best computers of the day. Their success was attributed to having a better process for interacting with the computers than the other teams.

“Where is the intelligence in that scenario?” asked Guszcza. “Is it in one of the chess programs? Is it in these two amateur chess players? No. The intelligence is an emergent property of five entities working together in a smart way.”

Human-centered design aims to facilitate effective human-computer collaborations. Guszcza introduced an analogy to explain the need for human-centered AI design. The success of Apple Computers resulted from the fact that Steve Wozniak’s focus on technology was paired with Steve Jobs’ focus on human factors: that people need to be able to use the technology without having to think too much about it. “Right now, I think the AI profession is full of Wozniaks and it’s waiting for its Steve Jobs,” said Guszcza. “We’re waiting for that broader notion of AI to take root.”

Guszcza made the case that actuaries are well positioned to fill this gap. Actuaries understand that data is usually messy, limited, and missing important information. “That’s part of our heritage that predated the data science revolution,” he said. “And it gets lost. It gets forgotten by people who have purely technical training.” Moreover, human-centered design involves having conversations with the users of AI systems, understanding the decision they’re trying to make, and incorporating that into the design of an algorithm. “By virtue of the fact that we’re a profession, and we have this ethos of a duty to society, I think that puts us in a good position to build these kinds of systems,” he said.

Guszcza closed by advocating for actuaries to have a broader role in designing predictive AI systems: “I kind of think we should own that space,” he said. “I think we should be doing a lot more outside of the insurance industry. We should be the ones building hiring algorithms or child support enforcement algorithms or medical decision support algorithms. It’s an expanded notion of risk, making decisions under uncertainty.”

Craig Sloss, PhD, FCAS, FCIA, is an enterprise analytics consultant at Definity Financial Corporation. He is a member of the AR Working Group.