Read this article in Spanish. Read this article in Portuguese.

Through our role as a member of the International Actuarial Association, the CAS engages in many collaborative efforts to elevate the actuarial profession around the globe. This article is the result of partnerships built through this engagement. In an effort to bolster inclusivity and share our activities with a wider group of international stakeholders, this article is available on the AR website in Spanish and Portuguese, courtesy of members of the Latin America Regional Working Group. Esperanza Borja Mead translated this article to Spanish and Rafael Costa translated to Portuguese.

About four billion of the world’s current population may benefit from inclusive insurance initiatives, but this potential market may not be easy to access from a traditional insurance perspective. Without inclusive insurance, we create the risk of leaving perhaps half the world’s population without access to insurance.

The usual indemnity perspective on insurance (for either individuals or businesses) focuses on financial recompense for specific losses incurred by the insureds. A broader perspective of insurance can also be taken. That is, the role of insurance is to mitigate the adverse impacts of risk events at both an individual and group/societal level. Mitigation, providing some form of safety net, and specific indemnity can be very different things.

The concept of risk sharing, as often formalized by insurance, is crucial to providing individuals and businesses with the confidence to take risks to advance economic growth. This positive economic role of insurance is encapsulated in the following, attributed to Henry Ford on the building of the Empire State Building:

The whole world relies on insurance. Without it, every person would keep their money without investing it anywhere for fear of losing it, and civilization would have ground to a halt a little past the Stone Age.

Rephrased, the basic objective of insurance is to provide confidence to take on risks by shifting the impact of specific risk events from being individually catastrophic to being manageable by a larger group. The usual, but not only, means to achieving this end is an indemnity focus for individual insureds.

The development of parametric, or index-based, insurance and disaster recovery programs, primarily in developing countries in an inclusive insurance context, provides an alternate path to social and ongoing economic benefit by moving away from a focus on individual indemnity to a broader group or societal focus. In other contexts, subsidizing (fully or partially) the costs of providing insurance can be validated by the longer-term societal and economic benefits reaped.

It is well established that access to insurance enhances economic growth, supports trade and provides other societal benefits. It is also well established that increased access to inclusive financial services, including insurance, helps to reduce poverty and can leverage social and economic development. These supports are especially valuable to those living near the poverty line, where one adverse event risks pushing them permanently below the poverty line.

Inclusive insurance

The International Actuarial Association (IAA)’s Risk Book chapter on Inclusive Insurance, IAA 2023, defines inclusive insurance as:

Insurance products through which adults have effective access to insurance and savings products offered by insurers through formal providers.

Effective access is explained as the involvement of convenient and responsible service delivery, at a cost affordable to the customer and sustainable for the provider, resulting in financially unserved or underserved customers being able to more effectively access and benefit from formal financial services in preference to other existing informal options.

Inclusive insurance products include all insurance products, indemnity-based or more broadly based, that are aimed at unserved or underserved markets. These markets typically are found in developing countries (from an insurance perspective) but are not restricted to such countries.

Microinsurance is a subset of inclusive insurance focusing on lower income populations. These large groups may be more vulnerable due to the nature of their activities, the environment where they live and their lack of resilience. The effects of climate change may exacerbate the hazards these populations face.

Scale of the challenge

The overall scale of the underinsurance challenge is highlighted by MAPFRE 2023, which states:

The world insurance deficit grows by 14.3% and comes to USD 7.8 trillion (equivalent to about 7.8% of global GDP) …

More than 77.6% of the current insurance gap is in emerging markets, a reflection of their great potential for growth.

Currently, China, the United States and India are once again leading the ranking of the countries with the greatest insurance potential in both the life and non-life segments.

More specifically in Latin America, McKinsey & Company 2023 report that:

Despite seeing the fastest growth in Gross Written Premiums (GWP) in the world, Latin America still has a low share of global premiums, at just 2% — versus 43% in North America, 28% in Asia, and 24% in Europe.

This is put into context by noting that insurance premiums in Latin America represent just 3.1% of GDP — versus 10.5% in North America, 6.2% in Asia, and 5.1% in Europe.

Inclusive insurance in developing countries

The inclusive insurance landscape is evolving rapidly. The most recent Micro Insurance Network (MIN) annual global survey reviewing inclusive insurance in developing countries, MIN 2023, highlights both the extent of coverage and the scope for expansion.

MIN 2023 notes that, in the countries included, about 330 million people are covered by microinsurance products. This is only perhaps one ninth of the population that could benefit from these products.

This supports the commentary that “results of this study point to a significant market opportunity for insurers, alongside a pressing need for governments to consider the need to close this substantial protection gap as a key enabler to meet wider development agendas.”

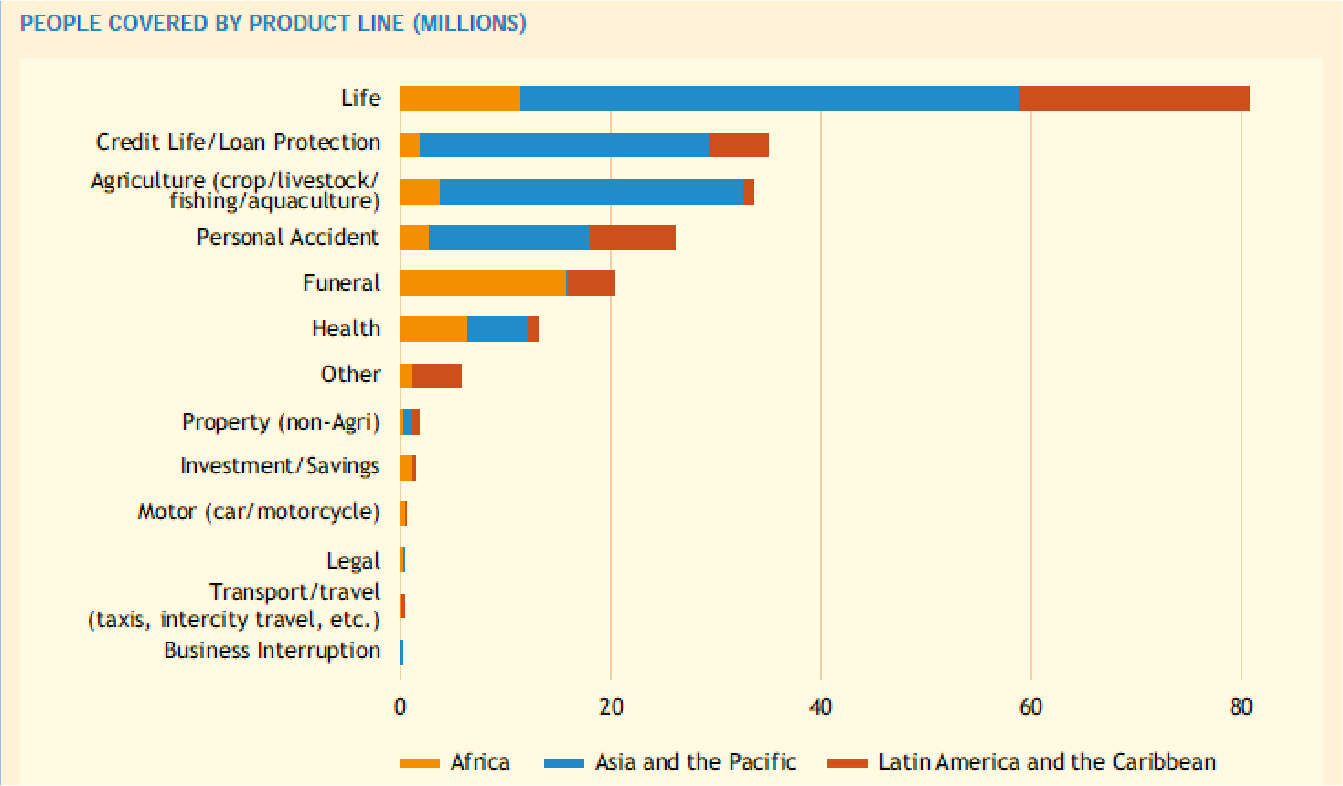

One overall measure of insurance coverage is number of policyholders (see Table 1).

Table 1. Coverage by number of insured in developing countries

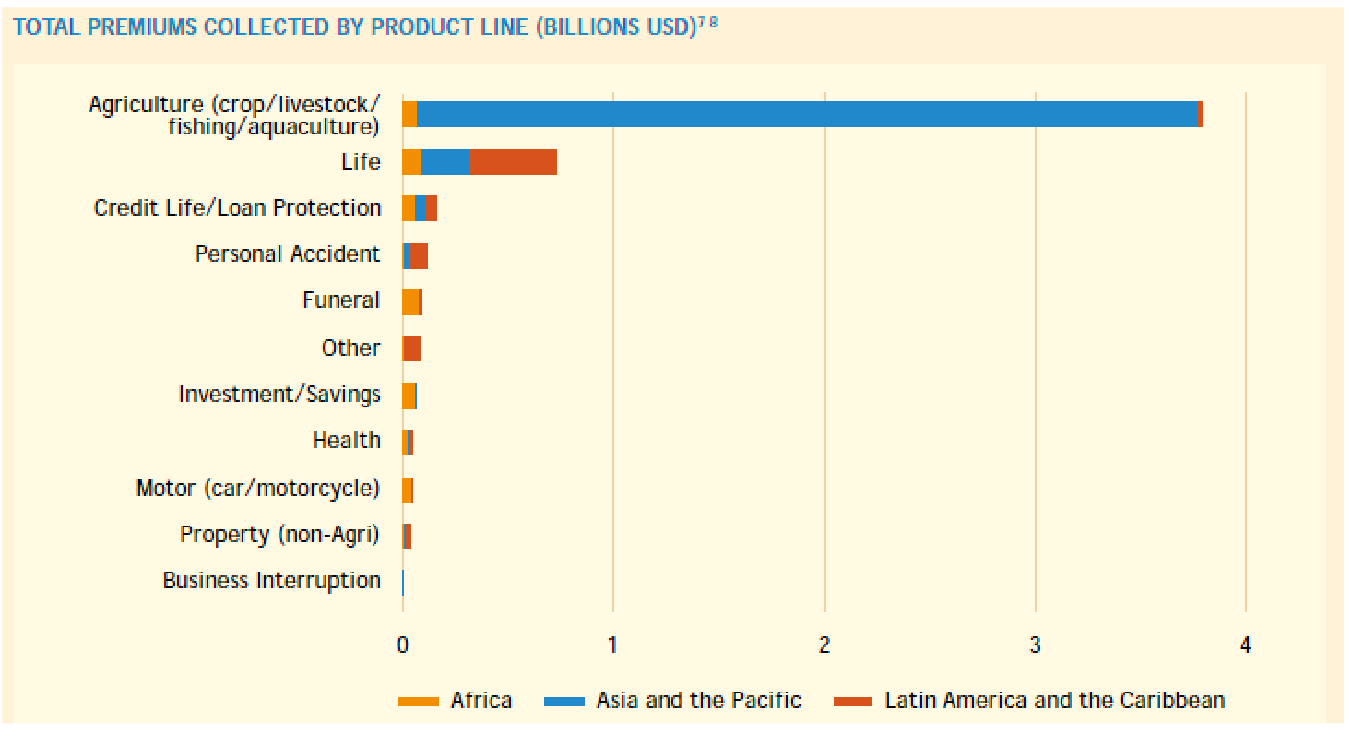

Another overall measure of insurance coverage is total premiums collected (see Table 2).

Table 2. Coverage by total premium in developing countries

Care should be taken when comparing regions (as in Tables 1 and 2) as product mixes may well vary, both between regions (on average) and between countries within those regions. Also, different aspects of insurance coverage are highlighted by different measures. For example, agriculture is the third largest product in terms of people covered but is responsible for more collected premiums than all other products combined. It is not uncommon for agriculture insurance premiums to be subsidized by governments.

There are also significant regional differences to be investigated in more detail, and these averages may vary significantly relative to the experience in individual countries in a region for a range of reasons. For example, in Latin America and the Caribbean, life insurance is the largest line of insurance by both premium and number of insureds. This pattern is not the case in the other two (developing) regions reported.

MIN 2023 introduces some measures for assessing inclusive insurance: market size and evolution, distribution and payments, social performance (relating to claims), women’s access to insurance, and climate risk and health. These measures vary markedly between regions, and this can be attributed, at least in part, to differences in products offered (both type and volume).

Inclusive and traditional insurance differences

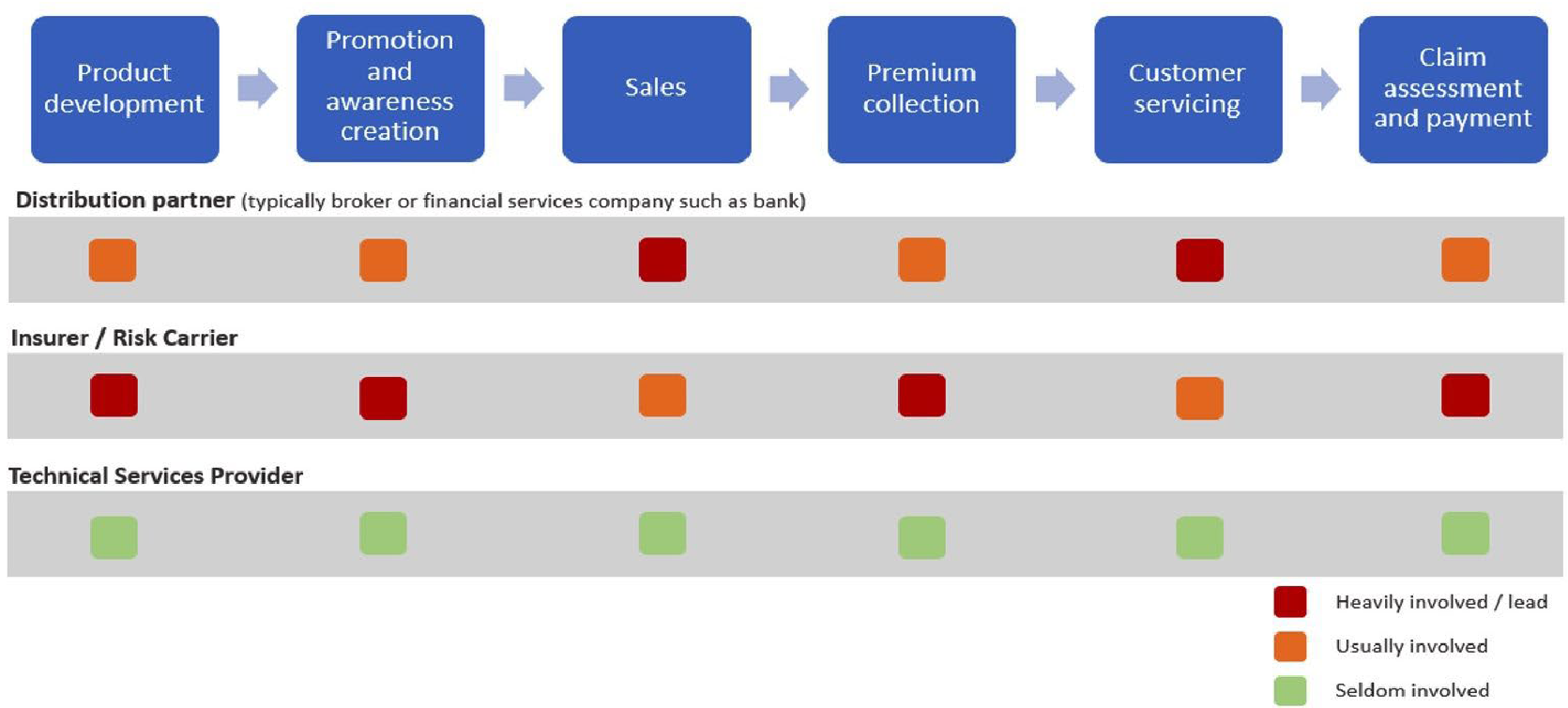

At a high level, there are three key roles in the insurance value chain:

- Distribution partner: Any player that has a role in the distribution of insurance. Several distribution partners may be working together or sequentially to distribute insurance to the customer.

- Insurer or risk carrier: Any party that accepts financial risk in return for payment of the insurance premium.

- Technical services provider (TSP): Provides technical services to a distribution partner, insurer or any other party in the insurance value chain. These can include actuarial, technology and data and international development services, or country- and market-specific knowledge on how to reach a type of consumer. TSPs are often the glue that holds the multiple partners of an inclusive insurance initiative together.

Diagram 1. The value chain for traditional insurance

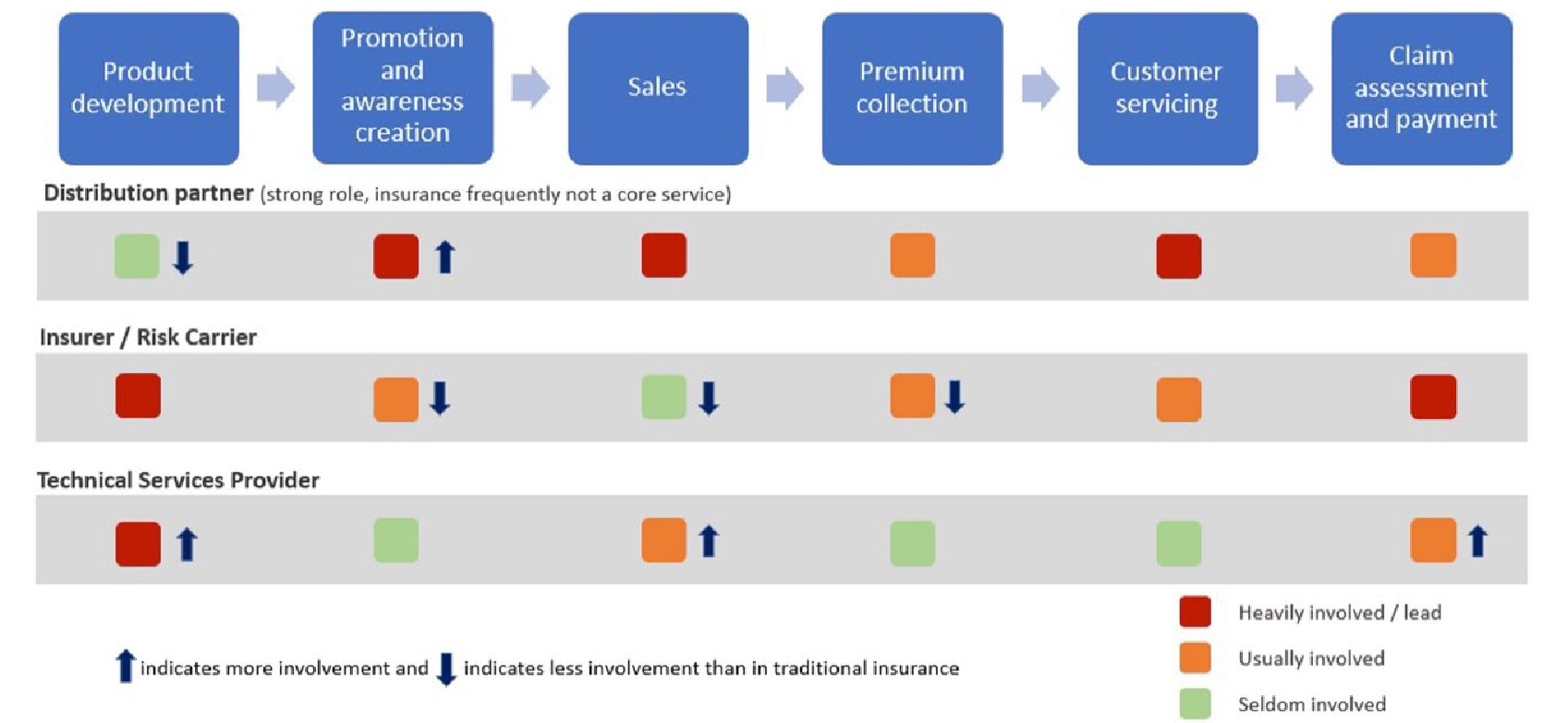

Diagram 2. The value chain for inclusive insurance

Diagrams 1 and 2 are taken from IAA 2023 and summarize the significant differences between traditional and inclusive insurance. As these value chains indicate, there will be variations in practice reflecting local conditions. The differences and the changes in the importance of various players are highlighted by the arrows in Diagram 2.

TSPs typically play a significantly stronger role in inclusive insurance than in traditional insurance, bringing skills and experience to inclusive insurance that more traditional insurers and distributors may not have. Multiple stakeholders are often involved in delivering key aspects of inclusive insurance, and some of these stakeholders (such as telecommunication companies) may be outside the insurance industry, something that differentiates inclusive and traditional insurance and often complicates effective inclusive insurance delivery.

Actuarial preconditions

From an actuarial perspective, the differences noted above reflect the context of actuarial work. In traditional, well-developed insurance markets, a number of pre-conditions are typically presumed:

- A ready supply of actuaries, the availability of actuarial education and the presence of robust professional standards.

- The availability of relevant, timely and appropriate data.

- Access to systems through which data can be collected and analyzed by providers, the industry and at the national level.

- A regulatory framework that is reasonably well-developed and understood by market participants.

We note that the above pre-conditions implicitly assume that coverages are available. With the increasing impacts of climate change emerging, compounded by increasing levels of material wealth to be protected, this assumption may be called into question. This may present more systemic issues to be addressed.

In many inclusive insurance markets, the reality may well be different, and one or more traditional pre-conditions are frequently not met:

- The supply of actuaries and the actuarial profession may be limited or nonexistent. The same applies to other insurance skills.

- Data may not be available or readily collectible. This may lead to country-specific mortality or morbidity tables or both not being available.

- Systems for collecting and analyzing data may not be well-developed or integrated.

- Customer understanding of insurance may be limited, especially for first-time customers of inclusive insurance.

- Trust in insurance may be lacking.

- Regulation that is appropriate for inclusive insurance may not be in place or, conversely, existing regulation may act as a barrier to inclusive insurance.

These issues are discussed further in IAA 2014, and some examples of how these issues could be addressed are given in Blacker 2015. A recent, high-level, structured approach to assessing the extent to which key success factors of inclusive insurance are addressed is given in Swiss Re 2023. Many of these drivers are not directly related to traditional actuarial considerations or to specific lines of insurance but need to be addressed if inclusive insurance initiatives are to succeed.

There is a risk that standard tools and approaches may not be appropriate in inclusive insurance markets, and that their application may lead to unintended outcomes, such as inappropriate premiums or claims processing.

For more information on the Risk Book inclusive insurance chapter, you can review the chapter itself (see IAA Risk Book), or you can watch two webinars delivered in February 2023 (see IAA Webinar:) that reflect on the findings from this chapter.

The challenge ahead

Globally, there is a great need for inclusive insurance products, both based on indemnity and more broadly. Actuaries can play an important role in the efficient, effective and sustainable delivery of these products. To achieve this, actuaries need to be aware of the differences between traditional and inclusive insurance products that reflect their environments and their consumers. They also should apply a flexible and holistic approach to achieve their ultimate objectives of providing consumers with confidence and protection when significant adverse risk events occur. An example of this flexibility is the development of index-based insurance.

The challenge for actuaries is how to take traditional actuarial knowledge and transfer it into an environment in which traditionally expected pre-conditions, actuarial and more broadly, are not met. This will require flexibility and resilience from actuaries and the capacity to apply underlying principles, as distinct from standardized “textbook” traditional practices. This challenge is compounded by the need to reflect the specific circumstances in specific countries. IAA 2017 provides some more insights that may assist actuaries considering pursuing inclusive insurance further. ●

References

“Assessing Risk and Proportionate Actuarial Services in Inclusive Insurance Markets — An Educational Paper and Toolkit,” International Actuarial Association, 2018. https://www.actuaries.org/iaa/IAA/Publications/Papers/Inclusive_Insurance/IAA/Publications/Inclusive_Insurance.aspx?hkey=20718186-6e51-457d-abde-cb1f7181a865.

Craddock, Christopher, et al., “Global Insurance Report 2023: capturando a próxima onda de crescimento na América Latina,” McKinsey & Company, September 2023. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/financial%20services/our%20insights/insurance/global%20insurance%20report%202023%20capturing%20growth%20in%20latin%20america/global-insurance-report-2023-capturing-growth-in-latin-america-portuguese.pdf.

IAA Risk Book: Introduction to Inclusive Insurance, Ottawa: International Actuarial Association, 2023. https://www.actuaries.org/IAA/Documents/Publications/RiskBook/IAARiskBook_InclusiveInsurance_2023-02.pdf.

“Issues Paper: Addressing the Gap in Actuarial Services in Inclusive Insurance Markets,” International Actuarial Association, 2014. https://www.actuaries.org/iaa/IAA/Publications/Papers/Inclusive_Insurance/IAA/Publications/Inclusive_Insurance.aspx?hkey=20718186-6e51-457d-abde-cb1f7181a865.

Actuaries in Microinsurance: Managing Risk for the Underserved, Jeff Blacker (editor). Winsted, CT: ACTEX Publications, 2015.

Aggerwal, Roopeli, Shelly Habecker, and Melissa Leitner, Swiss Re 2023, “The Life & Health Insurance Inclusion Radar — Why markets are more, or less, inclusive,” Swiss Re Institute, March 2023. https://www.swissre.com/institute/research/topics-and-risk-dialogues/health-and-longevity/life-health-insurance-inclusion-radar-publication.html.

Alice, Merry and Johan Rozo Calderon, “The Landscape of Microinsurance 2023,” Micro Insurance Network 2024. https://microinsurancenetwork.org/resources/the-landscape-of-microinsurance-2023.

IAA Webinar: The inclusive insurance risk book chapter, Sessions 1 and 2, International Actuarial Association, February 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=l_j2bK-AdEI and https://actuview.com/videos/introduction-to-the-iaa-risk-book-chapter-on-inclusive-insurance-part-22-3011.

MAPFRE Economics (2023), MAPFRE GIP 2023, Madrid, Fundación MAPFRE. https://documentacion.fundacionmapfre.org/documentacion/publico/es/media/group/1122068.do.

Jules Gribble, FIAA, CERA, Ph.D. is a principal at PFS Consulting, based in Sydney, Australia, and is a member of the IAA’s Risk Book Editorial Board. He can be reached at julesgribble@pfsconsulting.com.au.

Esperanza Borja Mead, FCAS, FSA, MAAA, is a principal at Actuarial Factor, based in Miami. She is a member of the CAS Latin America Regional Working Group. She can be reached at https://www.linkedin.com/in/esperanzamead/.

Eduardo Esteva, AFFI, MAAA, is a partner at Deloitte, based in Mexico City. He is the representative for Mexico in the CAS Latin America Regional Working Group. He can be reached at https://www.linkedin.com/in/eduardoesteva/.

Rafael Costa, FCAS, MIBA, is a risk engineer at Cruise in Los Angeles. Costa is chair of the CAS Latin America Regional Working Group. He can be reached at https://www.linkedin.com/in/rafael-costa-fcas/.

Statements of fact and opinions expressed herein are those of the individual authors and are not necessarily those of the International Actuarial Association, the Casualty Actuarial Society, the editors or the respective authors’ employers.