Technology makes cars safer and more convenient to drive but also introduces higher repair costs and new risks.

Oh, the promise of technology! Car enthusiasts and consumers alike appreciate technology’s shiny attributes. Whether offering better safety, convenience or just plain fun, car technology can also introduce unintended consequences, tipping the risk equation for better or worse.

For years, auto manufacturers have continually transitioned cars from mechanical machines to computers on wheels. The smarter the vehicles, the more expensive they can be to fix.

Auto repair costs were already climbing before the COVID-19 pandemic. Early in the pandemic, the lockdowns significantly reduced frequency, but claim severity escalated for many reasons (AR November/December 2023). As Americans log more miles on the roads, claims frequency will likely climb, and along with continuing high severity costs, will pressure losses.

Such developments are not promising when the personal auto line’s direct incurred loss ratio continues to climb. For 2022 and 2023, the dominant trend indicator of industry losses was in the 1970s, according to A.M. Best. Double-digit rate increases have helped tame the combined ratio. Still, more consumers are reducing coverage or dropping it altogether, increasing the population of underinsured and uninsured motorists.

While addressing this currently unpredictable line, actuaries must also look ahead as technology moves forward faster than ever. “We know tech has been improving, but we do not know where and how it is going to change,” said Jonathan Charak, vice president and emerging solutions director of sustainability underwriting at Zurich North America.

The next 10 years will be like no other in auto insurance history, Martin Ellingsworth, president of Salt Creek Analytics, predicted. “New vehicles are more expensive and have materials and technologies that will require additional people, processes and technology to service, maintain and repair. That will keep the pressure higher on the insurance markets to solve for future claims cost drivers.”

This article is part two of a two-part series examining the conditions impacting the personal auto insurance industry. The first article explored how the line moved from healthy to unprofitable (AR November/December 2023). Here, Actuarial Review takes a deeper dive into the potential impact of automobile technology along with insurance affordability.

Repair ramifications

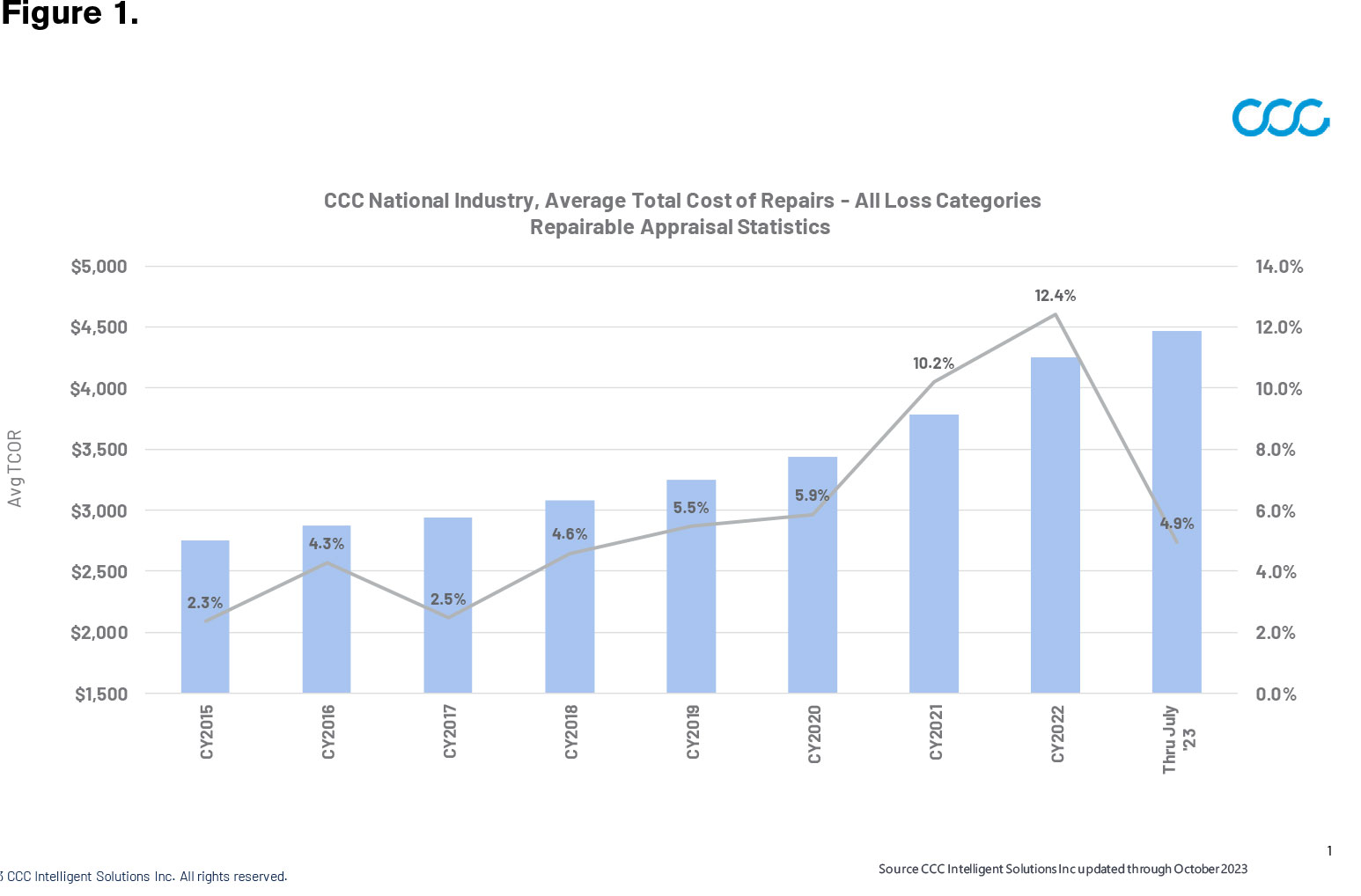

Experts agree that car repair expenses are significantly pressuring losses. Car repair costs rose by more than 5% from calendar year 2019 to 2020, escalating to double digits during 2021 and 2022, according to CCC Intelligence Solutions (CCC).

There is also a glimmer of relief. Although the average cost of repairing a car during the first half of 2023 is the highest ever at about $4,400, the rate of change from 2022 to the first half of 2023 declined by 4.8%. (See Figure 1.)

However, the contributors to higher repair costs, especially for technology, are expected to pressure premiums, experts agree. “Greater vehicle complexity plays a significant factor in the rising cost of repairs,” said Kyle Krumlauf, director of industry analytics at CCC. “The average vehicle today is equipped with 1,400 semiconductors and dozens, if not hundreds, of sensors and cameras,” he explained. Costs are also associated with the level of sophistication of parts, such as headlamps, and the integration of ADAS technologies.

Generally, cars with the most tech — whether they operate with internal combustion engines (ICE), electric motors (EVs) or have many advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS) features — tend to be luxury models that are more expensive to repair, said Xiaohui Lu, vice president of global business development for LexisNexis Risk Solutions.

ADAS to the rescue?

According to studies by the Insurance Institute on Highway Safety (IIHS), ADAS parts that the organization calls “collision avoidance technologies” can significantly reduce accidents and claims.

Despite promising results, there is not enough ADAS on the road to significantly reduce accidents, said Matt Moore, senior vice president at Highway Loss Data Institute (HLDI), IIHS’s sister organization. “The Advanced Driver Assistance Systems currently deployed in the fleet, while shown to reduce insurance losses, are not enough to compensate for the factors putting upward pressure on claim frequency when looking at all crashes (and) claims,” he added. Depending on the ADAS, it will take nearly a decade to a generation before the safety systems reach 95% of registered vehicles in the United States, according to HLDI research.

While recognizing the value of ADAS for reducing accidents and frequency, Roosevelt C. Mosley, principal for Pinnacle Actuarial Resources, said actuaries and insurers are asking the same question: “Does the decrease in accidents offset claims severity when a claim does happen?”

Everyone acknowledges the safety benefit for humanity, he said. “However, if ADAS costs insurers more, then you can argue it will not meet consumers’ expectations that as vehicle safety increases, insurance premiums should decrease. If ADAS costs insurers more, consumers will pay for it.”

Unfortunately, Mosley said, “safety devices were not designed with ease of repairability in mind.” However, there are some preliminary discussions with auto manufacturers to change that, he added, but it will take years before those changes will be in new cars.

Calibration also is necessary to ensure ADAS is working to its potential. Based on the higher incidence of post-repair issues, auto repair workers struggle with calibration, according to an IIHS study. About half of the vehicle owners with at least one of their ADAS applications repaired indicated system issues after job completion.

Autonomous ADAS

The quest for auto autonomy is contributing to different results than what was promised about 10 years ago. Back then, public policymakers and the general public were often told that 90% to 93% of accidents were due to human error and that automated vehicles would reduce auto accidents. (AR Driverless Utopia, May/June 2018) The Casualty Actuaries Society’s autonomous vehicle task force refuted aspects of the claim in 2014.

Some cars feature automated ADAS, which the Society of Automotive Engineers categorizes as Level 2 for vehicles that can simultaneously control steering, acceleration and deceleration. Adaptive cruise control and lane centering features create a partially automated driving experience.

The quest for auto autonomy is contributing to different results than what was promised about 10 years ago.

So far, there is little if any evidence that these Level 2 systems improve safety, but they can introduce new risks. “The problem is the better that the systems get, the more likely people will rely on the system, and the overreliance will lead to additional crashes,” said Greg Brannon, director of automotive research at AAA. “The challenge for insurers is to think about how to deal with this,” he added.

The more cars become automated, the more difficult it is to determine who — or what — is driving. “This uncovers a whole new set of issues,” Brannon said. Lane-keeping assistance, for example, introduces risk, he observed, because it can fight drivers for vehicle control and confuse who has responsibility for driving.

Partial automation encourages motorists to drive faster and engage in more distracting behaviors, David Harkey, president of IIHS and HLDI, told members of Congress on March 2023.

Meanwhile, there is concern that some manufacturers may have oversold the capabilities of their automated systems, misleading drivers to believe that the car can drive independently without assistance. Two specific examples are Tesla’s “Autopilot” feature and General Motors’ “Supercruise.” In response, IIHS is developing a rating system that measures the effectiveness of safeguards to ensure drivers are keeping their eyes on the road and their hands are either on the wheel or ready to grab it.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) is also tracking the safety of automated systems, Brannon said. The federal agency published a new standing general order in 2023 that calls on specific automakers to report crashes if Level 2 ADAS was used within 30 seconds of a collision under circumstances such as accidents causing fatalities or requiring medical treatment.

Because the driver must intervene with automated systems, manufacturers urge customers to keep their hands on the steering wheel and pay attention. Before the introduction of partial autonomy in vehicles, it probably would not have occurred to drivers to let go of the wheel in the first place.

“We do not believe in the promise of technology to replace drivers completely and for the vehicle to assume all responsibility for vehicle operations,” Harkey told Congress because the cars cannot and might not be able to handle every situation that arises.

Cars closer to being fully autonomous may not be ready for prime time either. Last summer, a fleet of Chevy Cruisers was introduced in San Francisco as a public transportation option. After several mishaps, the pilot program was canceled in October after a Cruiser hit a female pedestrian and dragged her 20 feet across the road.

EVs charging forward

Promising to improve the environment, electric vehicles (EVs) are growing in popularity. Besides attracting the interest of environmentally conscious consumers, public policymakers are encouraging automakers to put more EVs on the market.

As of second quarter 2023, there are about 3.7 million EVs in the United States, according to the Alliance for Automotive Innovation. More than half of EVs are luxury cars with more safety-enhancing ADAS features, said Lu of LexisNexis Risk Solutions. In contrast, China has 16 million EVs. The majority of them would be considered economy cars in the U.S. market.

More affordable EVs could be coming into the U.S. market within the next couple of years from both domestic and international automakers. NIO is just one Chinese auto manufacturer that plans to sell their vehicles in the United States.

EVs introduce new unknown factors and risks. The powerful torque instantly delivered by EV motors, for example, makes the cars accelerate faster when starting and could lead to parking lot accidents and speeding, Lu said. Drivers new to EVs need to retrain their muscle memory and become more accustomed to the different handling of the cars, due to factors that include regenerative braking, higher weight, and more powerful torque, he added.

In China, EVs have much higher risk than new ICE vehicles, and it takes about three years for the risk gap between EVs and ICE vehicles to narrow out gradually, he added. The latest research by LexisNexis shows a 31% higher paid claims cost for new EVs in the U.S. market.

Economy EVs in China have less powerful torque and shorter ranges, resulting in fewer accidents and less expensive repairs, Lu said. EVs are also vulnerable to battery damage because the batteries are bulky and make up much of the bottom of the vehicles, Lu added. Even a scratch of the packaging could allow water to get inside the battery packs and short them.

Then there are the fire hazards. A National Transportation Safety Board study reported that firefighters risk electric shock when putting out blazes caused by lithium-ion batteries. Besides being a concern for auto insurance, EV batteries are also a property risk, Charak of Zurich said. “There is also a (fire) risk of charging stations at office buildings and homes,” he added, asking, “How does it change the risks of those locations?”

What is known about electric vehicles is that they generally cost more to fix than conventional, or ICE, vehicles. Mosley said that most of the auto insurance industry’s knowledge about EVs stems from Tesla data. He added that there are not enough electric vehicles from other manufacturers to provide the best price coverage for EVs.

Even Telsa, which offers insurance in five states, “realizes that insurers were not crazy when they were not discounting insurance premium for Tesla cars as much as the auto manufacturer thought it should be,” Mosley said.

Electric parts of EVs are likely integrated into high-level assembly, Lu explained, making it difficult to fix individual parts and more likely that parts will be replaced as a whole, leading to expensive repairs. On the other hand, EVs in the Chinese market have similar claim severity as ICE vehicles, suggesting that design differences matter in repair costs and physical damage/property damage liability severity.

How quickly Americans will switch to electric cars remains to be seen. “Manufacturers are reducing or delaying production of EVs due to lack of demand,” said Louise Francis, president of Francis Analytics.

Despite subsidization, many Americans consider EVs to be unaffordable (see sidebar). “Moreover, the efficiency of charging electric vehicles is far below that of gas powered or hybrid vehicles. Even at fast-charging stations, a full charge takes at least half an hour and can take a lot longer depending on the type of charger, how fast the car is capable of charging and the length of the wait at the charging station,” she added.

Conclusion

Although insurers can deploy cost containment measures, the reality is that barring an unforeseen disruption, insurers and consumers will likely continue to bear much of the cost of continual technological evolution in vehicles and other factors pressuring insurance costs.

Affordability concerns

Realizing more safety ADAS and transitioning to EVs into the U.S. fleet largely depends on the willingness and ability of consumers to purchase vehicles with more technology.

However, Americans are holding on to their cars nearly four years longer than they did a generation ago. In 2023, the average car age was 13.6 years, up from 9.9 years in 2003, according to S&P Global Mobility.

Experts offer several macro trends to explain why Americans hold on to their cars, but one rarely mentioned explanation is personal finance. Car ownership is becoming increasingly expensive and unaffordable for many Americans.

According to a study by AAA, the average annual cost to own and operate a new car in 2023 is $12,182 — compared to $9,666 in 2021. Consider that in 2022, the median household income declined by 2.3% to $74,580, and the average cost of a used car was $26,213, according to Kelley Blue Book. New economy cars can range anywhere from $40,000 and up, and the price tag for luxury vehicles is at least $60,000.

Meanwhile, consumers feel the pinch of rising premiums for personal auto coverage and repairing cars. During the first half of 2023, 12 states reported a 30% or more increase in the share of uninsured drivers compared with the second half of 2022, J.D. Power reported in September. However, in five states, uninsured drivers decreased by more than 30%.

According to a survey by Jerry released in August, 23% of respondents indicated they settled for less coverage than they thought needed. About one in five chose a higher deductible in the past 12 months. Repairing and maintaining cars is also getting more difficult for consumers. Respondents in a survey by FinanceBuzz said the median availability of money to fix their cars was $765.

Annmarie Geddes Baribeau wrote this article as an insurance consultant. She is now the research manager at the CAS.