It might take more than raising rates to make this line healthy again.

For the first time in at least 30 years, if ever, the personal auto insurance line’s combined ratio is 112.2, according to AM Best. That means for 2022, insurers saw an underwriting loss of $12 for every hundred dollars they collected in premium.

AM Best is projecting that the combined ratio will be around 106.5 for 2023, demonstrating that higher rates are helping to cover costs. However, the loss trends are not looking much better in 2023.

In response, insurers are raising rates quickly by double-digits and pursuing undesirable options to reach equilibrium and return to profitability.

Individual insurers are responding by making tough business decisions. Roosevelt C. Mosley observed that some companies are announcing they are getting out of personal lines due to significant losses. “Others are facing surplus issues and being forced to exit,” said Mosley, who is the current CAS president and principal with Pinnacle Actuarial Resources.

Meanwhile, insurers might not be able to compensate for shortfalls in collected premiums with investment income. “Unless somehow returns are in the high double digits, the investment will not help as it has before,” Mosley said.

Insurance regulators are generally approving significant rate increases, he said. The hope is that regulators and consumers will tolerate the rate increases long enough to return the line to equilibrium.

Taking a look at the personal auto insurance industry’s dashboard, all indicators show a deteriorating line.

At the same time, if losses ultimately pressuring premiums do not abate, and if accident frequency continues to climb, the industry’s troubling situation will grow worse.

“Overall, the industry is not in trouble,” said Louise Francis, president of Francis Analytics, but some insurers have become vulnerable.

This article is part one of a series covering the conditions impacting the auto insurance line. This first article covers what made the line transcend from healthy to unprofitable. A future article will take a deeper dive into the potential impact of automobile technology and will offer ways actuaries can rethink pricing and reserving.

Losses, rates and premiums (Oh my!)

Taking a look at the personal auto insurance industry’s dashboard, all indicators show a deteriorating line. The combined ratio leaped a shocking 10.7% from 101.4 in 2021 to 112.2 in 2022, surpassing 109.4 in 2000, according to AM Best.

Verisk’s Fast Track Data shows that the loss ratio rose 15% from 82% for the four quarters ending 4th quarter of 2017 to a whopping 97% for the prior quarters ending 1st quarter of 2023. Since the rolling third quarter of 2021, the loss ratio has been the highest in recent memory. (See Chart 1).

Chart 1.

Just how much have rates risen? In 2023, “Filings are up more than 30-plus for physical damage and 20-plus for all coverages combined,” answered Frank Gribbon, actuarial director of personal lines core products at Verisk. He added that in 2022, filings were up 20-plus for physical damage and 10-plus for all coverages combined.

Mosley said he has never seen the pace of rate increases go up so quickly during his 30 years as an actuary. “Not only are insurers taking rate changes as fast as they can, increasing rates doesn’t stop the business flow,” he explained. Since a preponderance of insurers are universally raising rates, consumers can no longer find cheaper options like in the recent past.

For policyholders, the average premium for all U.S. cities increased a stunning 17.1% from May 2022 to the same month in 2023, said Francis, citing data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

Based on Verisk’s loss ratio data, where the first quarter loss ratio, rather than the four rolling quarters leading to it, declined for 2023, she said, “the rate increases in 2022 are having a beneficial impact.” While that is a positive development, carriers will need to continue increasing rates to lower the loss ratio, she explained.

Causes of loss

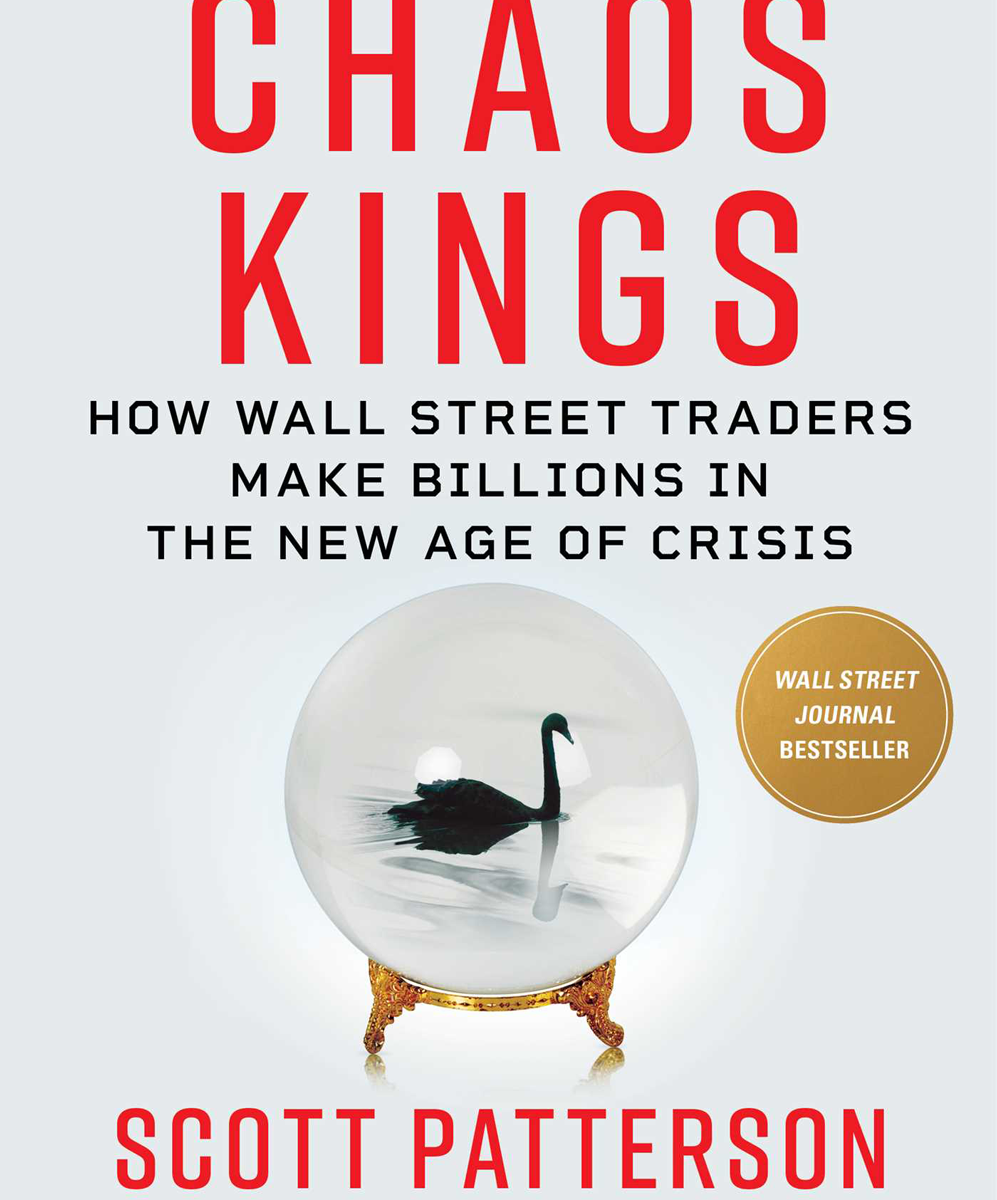

If there is a saving grace for personal auto, it is that since COVID-19, the number of claims has been below pre-pandemic levels. “Frequency went down during 2020 and 2021,” Gribbon said, but has been going up since. The number of paid claims for the prior four quarters ending in first quarter 2023 is reaching the pre-pandemic level of the four quarters ending in fourth quarter 2019. (See Chart 2.)

Chart 2.

Claim frequency stayed below pre-pandemic levels because fewer people were on the roads, said Alexander DeWitt, director and senior actuary of pricing analytics and actuarial services for Allstate. According to the U.S. Department of Transportation’s Federal Highway Administration (FHWA), miles driven — a proxy for exposure to accidents — declined by 38.5% in May 2020 compared to May 2019. This major indicator of risk remained significantly below 2019 levels through April 2021 and within 5% of the level in May 2019. “Actuaries will need to make adjustments due to rapid changes in mileage,” he added.

Losses primarily stem from car accidents, although those involving pedestrians and bicyclists also occur. Unfortunately, since the COVID-19 pandemic, primary causes of accidents such as distracted driving, speeding and driving while under the influence of alcohol or drugs, are on the rise.

According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), auto accident fatalities increased in 2021 to a 16-year high of 42,939 people. For 2022 the federal agency projects the number of fatalities to be down 0.3% to 42,795.

Plenty of evidence shows that driving behavior has become less safe since the pandemic began. The AAA Foundation for Traffic Safety’s 2021 Culture Index revealed an increase in unsafe driving behaviors between 2020 and 2021 after three years of steady declines. Further, an Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) survey looking at the propensity of drivers to engage in distracting behaviors revealed that 65% did so within the last 30 days.

Severity rising

When looking under the hood, there are several components — many of which insurers cannot control — pressuring claim severity upwards. First, inflation has been pushing costs in general (AR, May-June 2022). And though it is calming down, prices remain higher than in the fall of 2021 when inflation began its ascent well beyond pre-pandemic levels.

Some contributors to rising rates include medical inflation, climate catastrophes, social inflation and state regulations, but experts agree that the two primary contributions to claim severity are the repair and replacement of vehicles.

Most recently, the extreme cost drivers were not medical or bodily injury liability costs as Mosley has seen in the past, but physical damage. “I have never seen physical damage results this bad absent a catastrophe,” he said. “It’s not even close.”

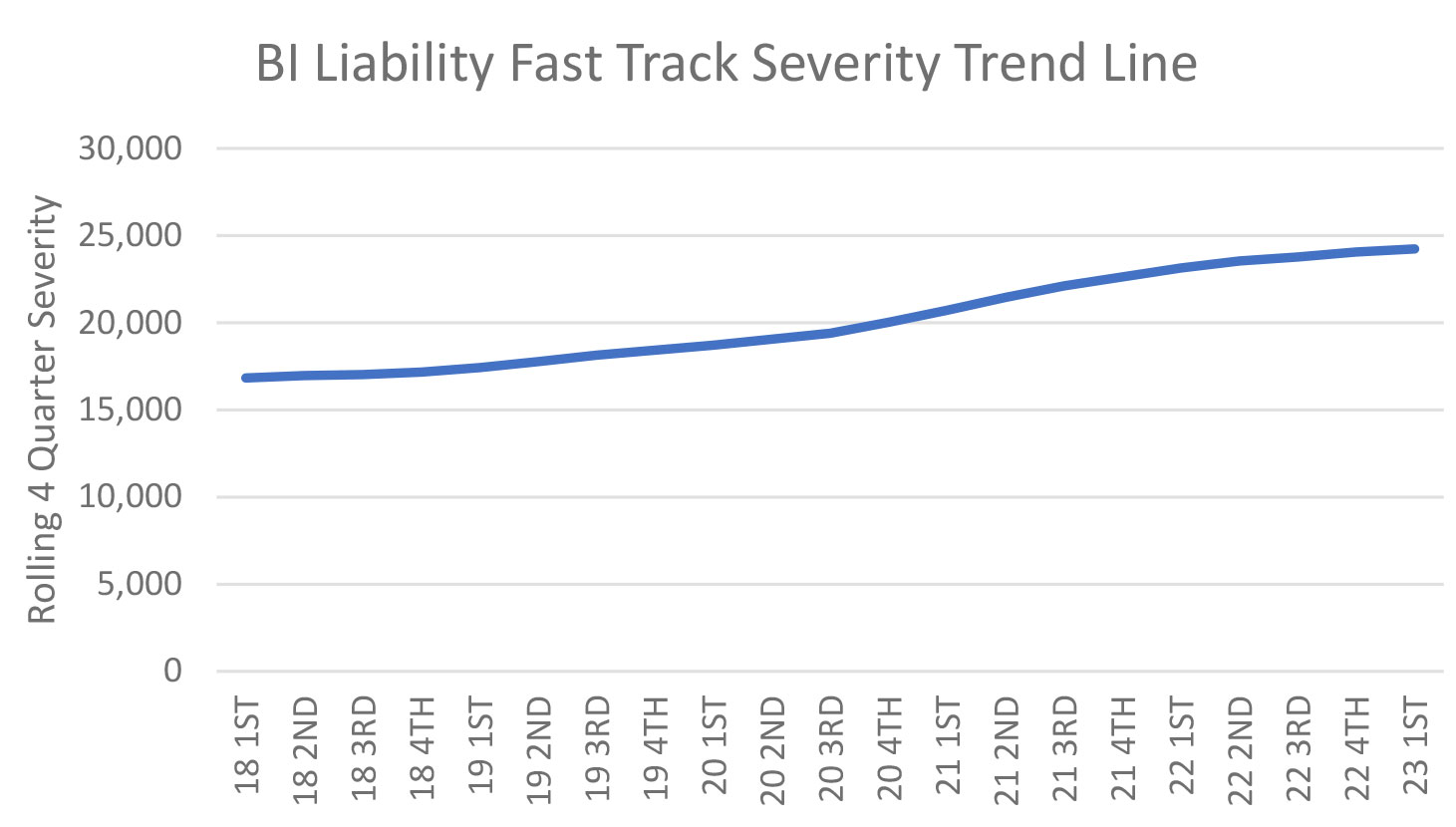

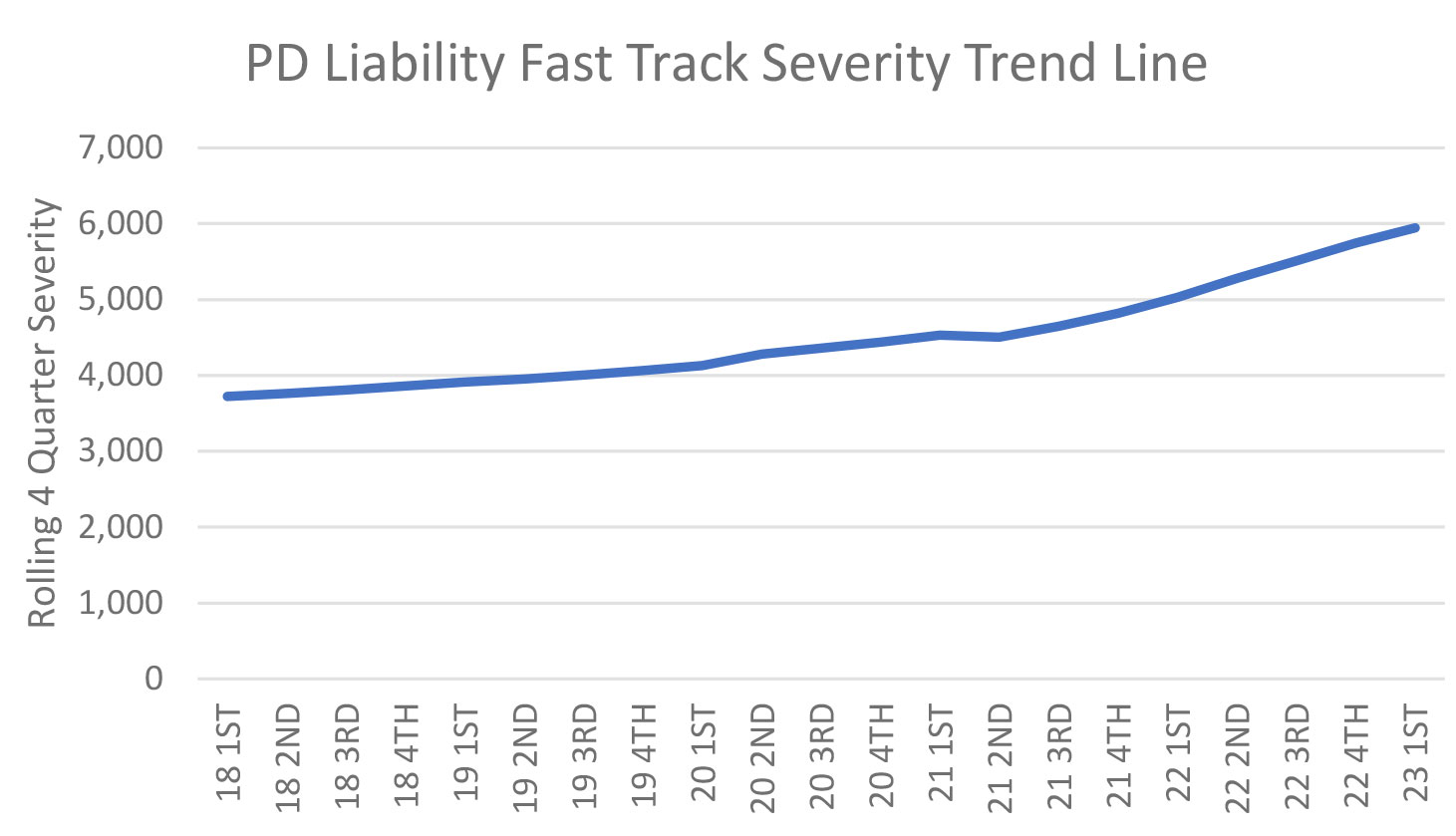

Claim severity trends driving rising loss ratios show that bodily injury liability severity rose 44% from $16,831 per claim during the rolling four quarters ending 1st quarter 2018 to $24,234 (See Chart 3a.) in the 1st quarter 2023, according to Verisk’s Fast Track Data. Property Damage Liability rose during the same period by 60% from $3,723 to $5,945. (See Chart 3b.)

Chart 3a.

Chart 3b.

Before COVID-19 arrived, insurers were already becoming concerned about physical damage costs, but the situation is now far worse. Since June 2023, repair costs have spiked by 39.9% since the same month in 2019, observed DeWitt, citing BLS data. In the most recent one-year period — from June 2022 to June 2023 — repair costs rose nearly 19.8%.

As a general rule, the more technological the car — whether it is loaded with advanced driver assistance systems (ADAS), partial automation or run by electricity — the more expensive it is to repair.

In the late 2010s, insurers noticed that previously simple repairs were becoming more expensive in high-tech cars (AR, November-December 2019).

Replacing a windshield offers a striking example. Windshield repairs have become more expensive due to head-up displays and ADAS, according to the Kelly Blue Book article, “It May Cost More Than You Think to Replace a Windshield,” published in March 2023. For cars with high-tech windshields, repairs now cost more than $1,000. A typical windshield repair is about $300 to $600 for a vehicle with little to no tech.

Repairing high-tech cars in the late 2010s was expensive, but there were relatively few. At the same time, the labor portion of repairing cars started to rise. Specifically, the mean wages for auto technicians rose by 13.9% from 2018 to 2022, said Katie Pipkorn, a consultant for Milliman, citing BLS data. In comparison, there was an 8.6% increase from 2014 to 2018.

There are several reasons why there is a shortage of auto technicians and why labor costs are rising. Some reasons mirror the causes of labor shortages in general.

Also, fixing late-model high-tech cars requires both mechanical and sophisticated technical prowess. Older, experienced repair technicians, who started their careers when cars were more mechanically based, can find keeping up with technology overwhelming, while younger, tech-savvy individuals find opportunities outside the auto shop. Unfortunately, the labor shortage is not expected to abate soon.

The COVID effect

The year 2020 began with insurers recognizing that repair costs were rising. The developments since COVID-19 arrived exacerbated some problems and introduced new ones that overlapped one another, complicating matters even more.

At first, the lockdowns were positive for auto insurers because they significantly reduced accident exposure, which impacts frequency. (See Chart 2.) Insurers, sometimes from regulator encouragement, returned premium dollars to policyholders.

As a result of the lockdowns, U.S. manufacturing, including auto production, significantly declined. Once workers could return with restrictions, the components necessary to move cars from the assembly line to the showroom became scarce, explained Martin Ellingsworth, president of Salt Creek Analytics. The short supply of microchips is the most notable example.

Because fewer cars were made, the value of new and used vehicles unexpectedly began to appreciate rather than depreciate as usual, Ellingsworth said. While the situation is a simple matter of supply and demand, the effects on insurers and consumers are complex and extensive.

… removing catalytic converters from hybrid vehicles for harvesting precious metal has also become a profitable criminal activity. Catalytic converter replacement can cost from $1,000 to more than $3,500, according to NICB, depending on the type of vehicle.

Pre-pandemic in January 2020, only 0.3% of new vehicles sold for more than the manufacturer-suggested retail price (MSRP), Pipkorn said, citing Kelley Blue Book. A year later, in January 2021, the percentage of new car buyers who were paying over MSRP had risen to 2.8%. By January 2022, she added, 82.2% of new vehicles sold for above MSRP.

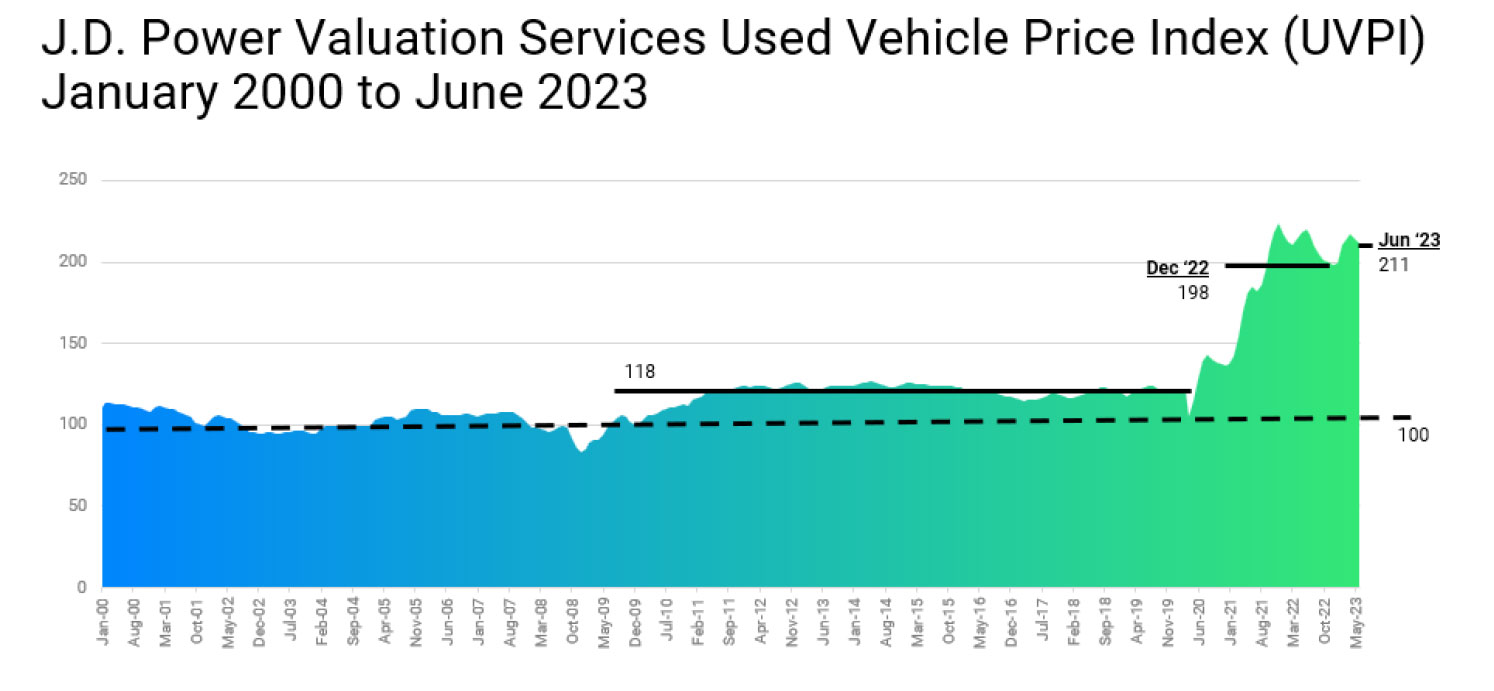

Automobile appreciation has several implications for insurers. For starters, replacing totaled cars has become more expensive. J.D. Power’s Used Vehicle Price Index shows the value of cars aged eight years or less has nearly doubled from 118 in January 2020, before COVID-19, to 224 almost two years later in December 2021. Used car prices cooled slightly in 2022, but as of June 2023, the index was 211. (See Chart 4.)

Chart 4.

“If the only factor in an insurance claim were the value of a like-for-like used vehicle,” Ellingsworth said, “then claims costs would have about doubled.”

Thankfully, new car prices are starting to calm down as manufacturing returns to pre-pandemic levels.

Meanwhile, Ellingsworth observes that used car replacement costs are likely to continue to move higher even though auto manufacturing productivity is increasing. “Given that the value at risk has gone up so much in so short a time, price increases will take time to adapt,” he explained. “The hollow fleet and low new vehicle production during the pandemic years will haunt the insurance industry for the foreseeable future,” he warns.

The replacement cost of vehicles is more severe because insurers total more cars. According to the LexisNexis Auto Insurance Trends Report 2022, the percentage of collision claims that result in total losses has risen 35% from 17% of collision claims in 2016 to 23% in 2021.

How much an insurer is required to pay a policyholder for reimbursement is determined by each state, explained Dan Hill, National Sales Director at CARFAX, who said the total loss formula is generally about 65% of actual cash value. He added that the formula has not changed for many years and is outdated, resulting in collision claims increasingly becoming total losses.

As a result, Hill said, “Many insurers are stuck with vehicle damage that exceeds the total vehicle loss threshold, so they are sold as salvage vehicles and either crushed, salvaged for parts or sold at auctions.” Unfortunately, vehicles sold at auction can be partially repaired or rebuilt and returned to the road. “These repaired vehicles have a significantly higher loss experience in future accidents,” he observed.

Insurers cannot do much to address the causes that are driving up physical damage costs. “So, the only recourse is raising rates and tightening underwriting,” Mosley observed. “We are going to be in this continuous cycle until inflation is under control or affordability issues become so acute that other, more significant actions must be taken,” he added.

While some issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic are expected to be resolved, it is unknown how the multiplicity of trends will develop.

With cars increasing in value, vehicle theft is trending upwards. For the first time since 2008, more than one million cars were stolen in 2022, according to the National Insurance Crime Bureau (NICB). The organization’s “hot wheels” list, which offers the top 10 most stolen vehicles, includes the usual suspects: Camrys, Corollas and pick-up trucks.

And though the theft of car components is nothing new, removing catalytic converters from hybrid vehicles for harvesting precious metal has also become a profitable criminal activity. Catalytic converter replacement can cost from $1,000 to more than $3,500, according to NICB, depending on the type of vehicle. Also, the NICB reported that insurers replaced about 53,000 in 2022, and that does not count replacements by manufacturers and auto owners.

A new wrinkle in car theft or hijacking is stealing cars just for fun. In 2021, the alleged, self-described “Kia Boyz” began posting instructional videos showing how to steal Kias and Hyundais solely for joyriding and vandalizing purposes, using only a USB charger and a flat screwdriver. The incidents occurred frequently enough that some insurers stopped covering Kias and Hyundais that lack theft-deterring immobilizers.

Over time, high-tech features will become more mainstream, adding cars that are more expensive to repair to the country’s fleet. The hope is that as more cars have ADAS features or become more autonomous, fewer vehicle accidents and claims will be filed.

Conclusion

Before the COVID-19 lockdowns, insurers recognized that property and physical damage expenses — primarily related to labor and cars with high-tech features — were growing. Since then, insurers have been grappling with unexpected developments arising from or during the COVID-19 era that will remain in play in the near future.

Increasing auto manufacturing productivity should help relieve vehicle shortage. However, since high-tech features are becoming more commonplace in new cars, insurers and consumers alike will continue to face high repair and replacement costs while hoping to reap the benefits of lower frequency sooner or later.

In the meantime, all signs point to claim frequency continuing to rise at a trajectory that will bypass 2019 claims frequency levels. Businesses are calling their telecommuters back to the office while driving habits are worsening. Unless the upward trends for physical damage and frequency reverse, insurers may face resistance to rate increases and will need to adjust approaches that made sense in the past.

Annmarie Geddes Baribeau is an insurance consultant and writer who has been covering insurance and actuarial topics for more than 30 years. You can email her at annmarie@insurancecommunicators.com.