Wherein an intrepid group of 18th-century insurers concoct an inspired plan to combat not only the treachery of piracy but the mercilessness of a masterful naval power.

The policy was free if you had a claim.

But if you had no claim, it cost more than the stuff you insured.

Some explanation: This was an 18th-century marine insurance policy. It insured the key parts of a voyage: the ship, its cargo, the cost of outfitting the ship and other shipping costs. Premium was due at the end of the voyage — but only if the trip was successful. If the trip was unsuccessful, the policyholder was reimbursed for all those losses, but the premium was, essentially, free.

And the unlikeliest twist: This policy actually made financial sense for both policyholder and insurer, a tiny crunch of the numbers shows.

It was an extraordinary policy, written in extraordinary times. It covered American ships during the Revolutionary War. Historian Hannah A. Farber describes it in her book, Underwriters of the United States, which shows how marine insurers in revolutionary and post-colonial America were instrumental in the building of the new nation. (See AR May-June 2022 for a review of the book.)

This wacky policy is a tiny, but fascinating, part of the book.

Shipping then was always perilous: sending cargo and crew across an ocean, dependent on waves and wind strong enough to propel the ship but not so strong as to destroy it. And pirates and privateers lurked. All of this created a robust insurance market. The most famous was Lloyd’s, but groups of merchants elsewhere copied the Lloyd’s model. Typical policies had a rate on line between 5% and 20% per voyage, depending on how long and how hazardous a journey would be.

A 75% rate on line is extraordinarily high, some 5 to 10 times higher than peacetime rates. Rates don’t get nearly that high now.

The American Revolution brought a new, greater risk: the naval blockade. The British strung an effective net between the American colonies and the rest of the world. In addition to the risk of catastrophes and rogue elements, merchants had to worry about the world’s eminent sea power seizing their ships.

The British were experts in the blockade. Years later, during a blockade coinciding with the War of 1812, a British admiral bragged he had seized, in a single year, American vessels worth more than £800,000. (A typical ship might be worth £2,500 to £3,000.) He added that the war would go on until insurers truly understood the likelihood of a ship to be seized.

Naturally, the cost of imports soared. Accusations of price gouging became common. Historian Farber cites riots in seven states over shortages of and high prices for rum, salt, sugar, molasses and tea. The Continental Congress suggested price controls, though this does not seem to have made much difference.

Merchants blamed the price of insurance. One merchant, under the pseudonym Mercator, explained in a newspaper article that salt worth £400 overseas had to sell for £15,500 in the colonies for the merchant to break even — largely because of the cost of insurance.

His detailed hypothetical was published in the Pennsylvania Evening Post on July 9, 1776, and so was hardly the most notable publication that week in Philadelphia. But Mercator’s discussion shows how distorted the insurance world had become thanks to the war. He was describing the wacky policy.

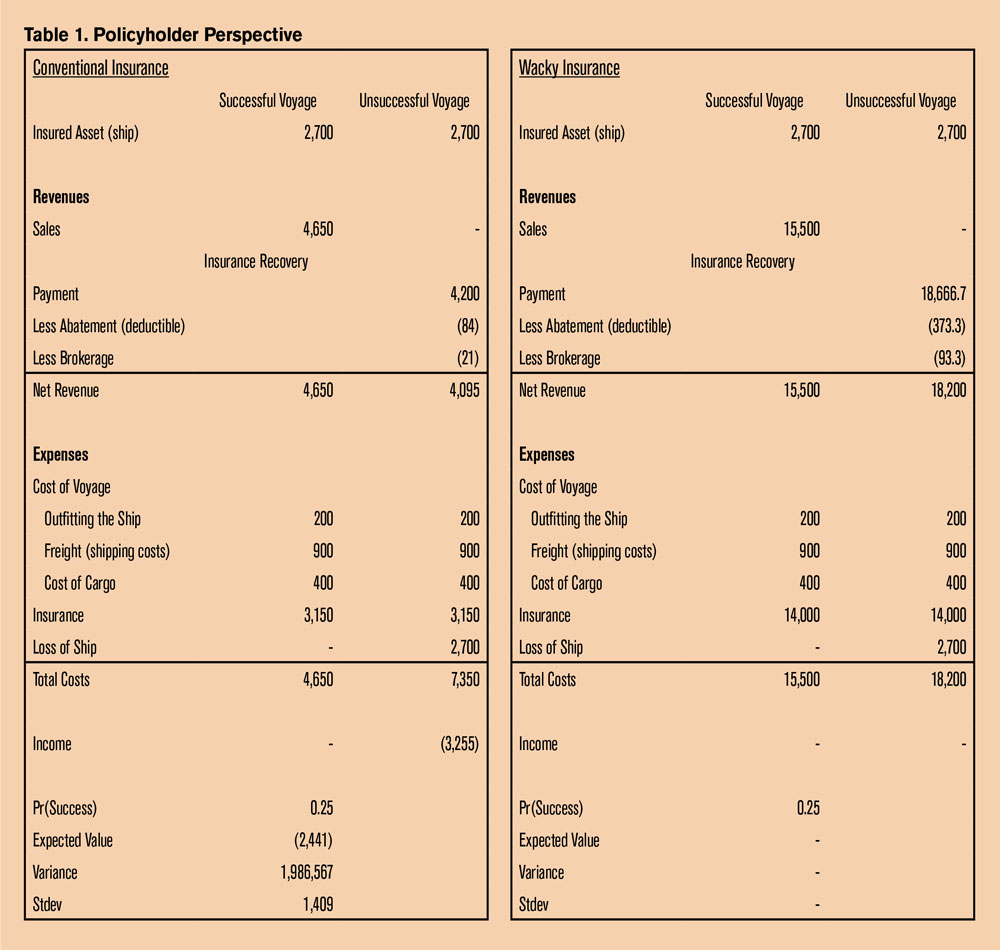

Normally, a marine policy covered the stated value of the ship (which he posited at £2,700) plus the costs of the voyage (£1,500), being the value of the cargo purchased from the distant port (£400) as well as the cost of outfitting the ship (£200) and other shipping costs (£900).

In peacetime, such a £4,200 voyage could be insured at, say, 10% rate on line, or £420. But the wartime rate, according to Mercator, was 75%, which works out to £3,150. (In her book, Farber adds a 0.5 percent brokerage to make the cost £3,171. I include the brokerage in the premium, to be consistent with how I interpret Mercator’s article. The difference doesn’t change any of the analysis.) In other words, the insurance cost twice as much as all the other elements of the journey put together.

A 75% rate on line is extraordinarily high, some 5 to 10 times higher than peacetime rates. Rates don’t get nearly that high now. John Miklus, president of the American Institute of Marine Underwriters, had never heard of such a rate. The closest he could recall was a rate approaching 40% on the reinsurance of satellite launches in the 1960s (with paid reinstatements).

To account for the high cost of cover, Mercator, in his calculation, included the premium as an insured item. If the ship failed to return, the merchant recovered the value of the ship, the costs of the voyage, and an amount equal to the cost of insurance. To do this, Mercator inflated the stated value of the voyage from £4,200 to £18,666.67 — or £18,666, 13 shillings, 4 pence. (Back then there were 20 shillings in a pound and 12 pence in a shilling. The U.K. converted to decimal currency in 1971.) At 75% rate on line, the premium came to £14,466.67.

So, the insurance on £4,200 of stuff cost more than three times that amount. But you only paid the premium if the voyage was successful.

In case of a total loss, the recovery reimbursed the merchant for the ship, the cargo, the cost of the voyage and the cost of the insurance policy, including 0.5% brokerage and 2% for a sort of deductible known as an abatement. However, merchants regularly netted out amounts they owed each other. The policy was effectively free if the merchant sustained a total loss.

I’ve laid out the alternatives — the conventional policy and the wacky policy — in Table 1. For each policy, I’ve spelled out two alternatives: a successful voyage, where the journey ends perfectly, and an unsuccessful voyage, where the ship is seized or lost. (In the real world, partial losses were common. Farber actually begins her book with an example of how insurance would handle a typical partial loss — one with some cargo spoiled, the itinerary rerouted and a ship damaged en route, among other complications.) I’ve shown revenues and expenses in each case and calculated income. Consistent with a 75% rate on line, I’ve placed the probability of a successful journey at 0.25.

Table 1 shows why the wacky policy had its adherents. It made better business sense. As described by Mercator, the voyage breaks even regardless of its result. A conventional policy has a negative expected value. Even a crude risk measure like standard deviation shows that after buying a conventional policy, substantial risk remains.

Farber, the historian, found the wacky policy was a widely accepted practice, though hardly universal. The policy made sense from the insurer’s perspective.

With both policies, the insurer profits as long as the probability of a successful journey is greater than 0.23. With a probability of success of 0.25, the conventional policy has an expected profit of £79 while the wacky policy has an expected profit of £168. The wacky policy has a more variable result, but the coefficient of variation of both policies is the same. As long as the insurer has the capital, profits will be greater selling the wacky policy. (See Table 2.)

Today an insurer would weigh an additional risk: adverse selection. Clearly this practice depended on the merchant returning to the same insurer on his next voyage. This wasn’t a bad bet in the 1770s, though.

The nation was smaller and more fragmented. Merchants and insurers knew one another. In fact, a group of merchants often operated the insurance companies. If a merchant ripped off his carrier, he was ripping off his friends and colleagues, and perhaps himself. His next voyage would be harder to assemble and insure.

And he couldn’t skip town. We think of this era as one in which you could disappear from one town and start a new life down the road.

That was possible for a tradesman (think blacksmith), Farber said, but not a prominent business leader. Much of his prowess depended on his reputation and his knowledge of and connections in the community. Even the savviest would be unlikely to reproduce success in a new town.

“People with that much money don’t have that many ways to escape,” she said. “You couldn’t maintain your quality of life with a fresh start.”

It was also difficult (though not impossible) to buy cover from an insurer elsewhere. The merchant might know little about a prospective insurer. As so often in insurance, reputation and trust are critical but hard to assess. And during the war, it was hard to justify insuring through London.

All of this mitigated the risk of adverse selection.

The insularity had another benefit, a point that Farber made in her book. It let merchants blame insurance companies for high prices without mentioning that the insurers were largely owned and operated by the same merchants. Merchants effectively shifted their wealth from their shipping pocket to their insurance pocket and were able to shift the blame for charging exorbitant prices.

I showed my calculations to Farber. She quickly pointed out that 18th century businesspeople didn’t think so much about bottom line profits. They rarely thought beyond 6 to 18 months, and they were more interested in keeping their business afloat than in accruing wealth.

“I think of it like a poker game,” she told me. “The goal is not to go bust.”

Jim Lynch, FCAS, MAAA, recently retired from his position as chief actuary at Triple-I and has his own consulting firm.