How predictive is the past when future risk is unfathomably dynamic?

Cyber insurance actuaries face a challenging reality. While claims data availability is growing, relying on past information to predict future losses is just not enough. As the burgeoning cyber insurance market, emerging cyber vulnerabilities and unfathomable risk continue, actuaries are charting new territories to help insurers confidently write coverage.

To appreciate the pace of change, consider how the cyber world has shifted in the past three years. Harrowing data breach headlines began to dramatically boost cyber insurance sales. Public awareness of the internet of things was just beginning, and cloud computing was considered safe.

Fast forward to today. Increasing cyber insurance sales have led to additional claims data, but risk and coverage continue to change. Ransomware claims are on the rise while greater connectivity from cloud computing, the internet of things and sophisticated automation are introducing new cyber vulnerabilities. “The attack surface of an organization is loosely the sum total of all points of vulnerability,” says Jon Laux, head of cyber analytics at Aon Benfield.

More organizations are buying cyber insurance for the first time or are expanding it. While the insurance industry has responded with higher limits, customers also want cyber insurance to cover more types of risk.

Market Overview

Cyber insurance has existed in some form for about 20 years, and it remains a developing insurance line. Cyber insurance is offered through stand-alone policies or as an add-on to traditional business coverage such as general liability. There are more than 60 different cyber insurance carriers that offer great variation in coverage scope, policy triggers, definitions and exclusions, according to the Aon survey “Cyber — The Fast Moving Target,” released in June 2016.

Coverage categories identified by Marsh & McLennan Companies include business income, data asset protection, event management, cyber extortion, privacy liability, network security liability, privacy regulatory defense costs and media liability. These competing policy forms have little uniformity, says Robert Parisi, Marsh’s cyberrisk product leader.

Growth as measured by premium continues in the United States. Estimates of growth vary. Parisi points out that the general market consensus is that 2016 closed out just shy of $3 billion in gross written premium, up from $2 billion in 2015 and $1.5 billion in 2014.

Aon’s estimate is lower, with the current size of the global cyber insurance market at about $2.5 billion. Laux says that the U.S. market is 80 to 90 percent of the global market and that 60 to 70 percent are stand-alone policies. Aon estimates the global market is expected to grow to $7.5 billion to $10 billion by 2020.

Stand-alone cyber insurance purchases among Marsh clients in the U.S. rose 27 percent from 2014 to 2015, according to Marsh’s MMC Cyber Handbook 2016, released in November 2016. This was mainly driven by an increasing awareness and appreciation of cyberrisk, particularly at the boardroom level. “We saw the same increase (26 percent growth) between 2015 and 2016,” Parisi says.

Despite the unfathomability of future risk, insurers continue to compete for more business. Generally, cyber insurance has been profitable.

Michael Solomon, a consulting actuary with The Actuarial Advantage, Inc., calculated that cyber insurance stand-alone polices in the United States have a loss and loss adjustment expense (LAE) ratio of 65.2 percent based on figures from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners’ (NAIC) Cybersecurity and Identity Theft Insurance Coverage Supplement for 2015 statutory filings. Using updated NAIC information, Aon estimates the loss and LAE ratio for the United States at 50 percent for stand-alone coverage and 41.5 percent for both stand-alone and cyber coverage packaged with other insurance lines.

“Profitability has varied widely, with even carriers who have substantial books of cyber insurance business recording loss and LAE ratios from as low as one percent to as high as over 160 percent,” says Alex Krutov, president of Navigation Advisors LLC. Krutov, who started and was the first chair of the CAS Cyber Insurance Task Force, says that the median loss and LAE ratio is less than 40 percent for narrowly-defined stand-alone cyber insurance.

Companies buy cyber coverage for various reasons. According to the June 2016 Aon survey, the majority of survey respondents that purchase cyber insurance (68 percent) cite balance sheet protection as the main motivator.

Despite the unfathomability of future risk, insurers continue to compete for more business. Generally, cyber insurance has been profitable.

Customers also want broader coverage. The growing need to cover business interruption and contingent business interruption risks, for example, is due to expanding dependence on technology, Parisi observes. “(This is) the most significant thing going on in the cyber market,” he explains, because traditional business interruption coverage generally does not cover losses when cyber incidents are the cause.

Business interruption, both during a system breach and post breach, was rated as the top cyberrisk concern, according to the Aon report. Bodily injury/property damage, which is generally covered in first- and third-party coverage, was the lowest rated concern of respondents.

“The reality is the traditional cyber insurance product in the U.S. has largely been developed to address data breaches with some ancillary coverage,” Laux says. “That leaves a lot of ground uncovered for a manufacturing company that could have major cyberrisk if hackers get into the control systems of a manufacturing plant.”

Policies are starting to pick up business interruption risk, Parisi observes. “What we have seen in cyber (insurance) is a fairly quick research and development cycle with awareness of the risk being recognized by the buyer and then carriers assessing how much of that risk they are willing to accept.”

More unintended consequences from the internet of things, for example, will lead insurers to ask more about their own risk aggregation and possibly to change how they provide coverage for risks associated with connected devices, according to Marsh’s report, “The US Casualty Market In 2017: Our Top 10 List,” published in January. Due to greater connectivity, the report notes, “[t]he boundaries blur between traditional product liability and cyber insurance.”

Data Desire

While all indications point to a growing demand for cyber insurance, insurers face the ongoing quandary of providing coverage amid a plethora of unknowns.

Cyber insurance is different from other types of insurance in at least one significant way: The traditional actuarial adage that the past is the predictor of the future has limited application. Further, actuaries involved in cyber insurance differ on whether there is enough quality data for reliable modeling.

“Many people are still saying we just need more years of data,” Krutov says. “However, in cyber insurance, you cannot just use historical data the way it is done in traditional actuarial models — even if we had a lot more of this data.”

“Actuaries and insurers have enough claims data to tell a useful part of the story but not the whole story,” observes Michael Solomon. He sees the lack of data as an opportunity for actuaries to demonstrate their value, which is evaluating risk using their experience and unique actuarial judgment.

While claims data offers more insight than insurers had three years ago, the data situation remains less than ideal. Sources agree that data quality is a pressing concern. Data standardization “will go a long way” to improve data quality and consistency, says Robert Hartwig, clinical associate professor and co-director of the University of South Carolina’s Center for Risk and Uncertainty Management. Hartwig is the co-author of the Insurance Information Institute’s report, “Cyberrisk: Threat and Opportunity,” released in October 2016.

Hartwig says that cyberrisk has the potential to permeate every insurance line. The internet of things, for example, will affect auto and home insurance. Advanced medical devices will have an impact on workers’ compensation. “There will even be workers who will be wearing, ingesting, or implanting devices to assess workplace injuries,” he says.

Since risk profiles are growing in relevance, insurers need to collect more information about their insureds. “When we ask insurers to provide us with information to run models, the reality is that most insurers simply are not capturing enough data,” Laux says. A set of common core data requirements for cyberrisks was published in 2016 by Lloyd’s of London in conjunction with modeling firms Risk Management Solutions and AIR Worldwide. This was a good start, Laux notes, but it will be some time before insurers are actually capturing the relevant data fields for modeling.

The cyber insurance underwriting process evolved out of errors and omissions (E&O) coverage questionnaires. While cyber insurance has things in common with E&O insurance, Laux says, the information needed to thoroughly grasp cyberrisks goes well beyond what underwriters are typically asking. “The information needed is much more subtle,” he adds.

Data collection, however, relies greatly on the willingness of underwriters to ask more questions. “A real issue is not wanting to impede the sale,” Parisi says. Some insurers are looking at organizations in specific industries with so much scrutiny that Parisi observes that they risk “paralysis by analysis.” This is especially true for business segments hit hard by breaches over the past two years and for new coverages, such as contingent business interruption coverage.

Underwriters also continue to have tremendous influence on what insurance companies ultimately write. Actuarial influence varies widely depending on the insurer.

Alternative Information

Since claims data has limited use in predicting losses amid the continual influx of emerging cyber vulnerabilities and losses, actuaries are seeking alternative data sources and methods to prepare insurers to cover future claims.

Actuaries need to loosen their expectations about what data should look like and where to find it, Laux says. Because each data set has strengths and weaknesses, the key is to use the right data to solve the right part of the problem within tight parameters.

Since insurers and cybersecurity firms share an interest in understanding the factors that contribute to cyberrisk, along with frequency and severity of incidents, experts agree that using nontraditional insurance data makes sense. “The reality is there is a massive amount of data being gathered every day, but it sits in the systems that defend companies, [in] technology servers and on the internet for those who know how to look for it and capture it,” Laux says.

“The most interesting area we’re grappling with as an industry,” he says, “is how to take all this technology data, which can be seen as leading indicators or signals of cyber compromise, and turn that into intelligence about the probability of a claim and its size.”

Incident data from cybersecurity firms and other sources, Krutov says, offers insight into both frequency and severity of potential cyber events. Information on uninsured financial losses is another nontraditional data source, he suggests. “Actuaries are usually very reluctant to use this type of data because there is a big difference between insured and uninsured financial losses even where loss events appear to be similar.” While the reluctance is justified, Krutov believes this information is useful in modeling risk for both existing and new kinds of cyber insurance coverage.

Before his company had sufficient claims data from 10 years of selling cyber coverage, it was still able to develop models using other sources of data, says Adam Rich, actuary and head of specialty lines analytics for the Beazley Group. “We simply built a model to try and parameterize the things that might give rise to payments under a policy,” he adds. Such factors include claims frequency by size, amount of forensic or legal expenses, the cost of notification services and monitoring of credit — as well as the chance that those services would be needed or requested.

Solomon recommends keeping up with cyber reports and paying attention to international trends — especially in Western Europe — since cyber incidents are independent of geographic location. “We are looking for causes of loss and where the malicious actors are going, which can be learned from the experience of other countries,” he says.

Modeling Uncertainty

Experts have different opinions concerning just how far along cyber modeling is developing.

[Hartwig] likens the state of cyber insurance modeling to the late 1600s, when Lloyd’s of London was insuring ships headed to the New World with little information for determining risk potential.

Poor quality data requires insurers to analyze cyberrisk “from a technical rather than a statistical point of view,” according to The Geneva Association report, “Ten Key Questions on Cyber Risk and Cyber Risk Insurance,” published in November 2016. When it comes to factoring in the fast-changing risk landscape, the report states, “There is no established method to model cyberrisk, and not much research has been done so far.”

Hartwig says that cyber modeling — especially for catastrophic loss — is in its infancy. He likens the state of cyber insurance modeling to the late 1600s, when Lloyd’s of London was insuring ships headed to the New World with little information for determining risk potential. “We actually have zero data on the much-feared ‘cyber Pearl Harbor’ or ‘cyber 9-11’ attack scenarios,” he says.

Laux contends that model development has come a long way in just the past couple of years. He explains that, in 2015, the discussion at industry conferences was about whether cyberrisk could be modeled. Now, the conversation has evolved from abstract ideas to a working discussion. “And I expect the pace of development will continue,” he adds.

Modeling innovation is largely coming from cybersecurity firms that use analytics to protect their customers, Laux says. “The single biggest area of excitement in terms of analytics in this space has to do with the influx of technical and cybersecurity firms providing analytics,” he observes. “Insurance has become a use case.”

Krutov offers that cybersecurity models tend to focus on quick detection of anomalies. This makes them less useful for insurance pricing because a longer-term time horizon of at least a year is necessary. “Very often the choice of models, whether complicated or of the back-of-the envelope variety, is driven by data availability,” he says.

Rich insists there is enough data available to create pricing models. Beazley deploys several different cyber models according to the insured’s characteristics and the amount and type of coverage. The insurer also monitors an insured’s portfolio from an aggregate view while segmenting it for emerging trends.

To determine the likelihood that a customer could become a cyber incident target, Laux says that Aon recommends conducting a risk analysis of each customer using factors such as company size, industry and security posture. Cyberrisk modeling needs to go beyond considering previous cyber losses. It needs to anticipate the shifting nature of exposures and to contemplate cyberrisk as a peril rather than as a narrowly defined coverage.

For severity modeling, Solomon looks at costs from losses already covered by other types of insurance, such as intellectual property or theft. He uses this information to determine potential insurance losses due to cyber incidents. Outside data can also provide insight. “Even the cost of business interruption not from the insurance field is helpful,” he adds.

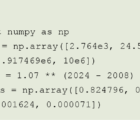

According to The Geneva Association report, modeling frequency and severity can be accomplished by using extreme value theory and the peaks-over-threshold approach. “Heavy tail distributions have been proposed, [e.g.,] the power law or the log-normal distribution for the severity and negative binomial distribution for the frequency,” the report notes.

Emerging Risks

Although inroads are being made to address data availability, modeling emerging risks will always be challenging. Continuous revisions of modeling techniques are necessary in a quickly-changing technological environment, the Geneva Association report notes.

Sources agree that anticipating the cost potential for emerging risks is challenging. Besides using cybersecurity data to detect risks, claims and underwriting professionals can also provide insight into emerging trends.

The growth of ransomware is one emerging trend. Criminals are figuring out that ransomware is a much more efficient way to make money, Solomon says.

At Beazley, claims stemming from ransomware attacks have more than quadrupled in 2016. Nearly half of these attacks occurred in the health care sector, according to an internal study posted on its website in January. Such attacks will double again in 2017, Beazley projects. “We are paying out more of those, and even our policies are starting to include language to explicitly state how much we will pay for ransomware,” Rich states. The company pays in Bitcoin as a service to customers, he adds.

Two more emerging risks stem from greater connectivity through the internet of things and cloud computing, Parisi says. Both are making insurers and insureds cautious, Parisi notes.

“As more things get connected to the internet,” Rich explains, “the distribution of connectivity might change an insured’s exposure.”

Conclusion

A convergence of conditions is having an influence on cyber insurance. Insurers will continue to face pressure to expand coverage amid unpredictable new risks stemming from greater automation and connectivity from cloud computing and the internet of things. The much-feared and impossible-to-predict “cyber catastrophe” that could cascade through multiple organizations remains an aggregation concern for insurance companies.

While data is becoming available for more meaningful models, underwriters continue to rely greatly on their own judgment for writing coverage. Just as it takes time for underwriters in other lines to trust modeling results, so too will actuarial influence grow stronger.

The much-feared and impossible-to-predict “cyber catastrophe” that could cascade through multiple organizations remains an aggregation concern for insurance companies.

Cyber coverage policies and data collection call for greater standardization — especially as small- and medium-sized organizations are beginning to realize their own vulnerabilities and need for cyber insurance. Hartwig predicts there will be robust penetration in the middle markets in 10 years as the insurance industry grows more comfortable covering cyber “fender benders.”

Hartwig says that the actuarial profession will need to update exams and provide continuing education so its practitioners will remain relevant. He predicts, “An actuary specializing in cyber and technological risk will have a great future.”

Annmarie Geddes Baribeau has been covering actuarial topics for more than 25 years. Her blog can be found at http://insurancecommunicators.com.