The U.S. property and casualty industry is facing increasing challenges with the possibility of an extended period of inflation and rising interest rates. At the same time, social inflation — rising loss experience related to litigation — continues to pressure claim severity, despite pandemic-related court delays. The first general session at the 2022 CAS Spring Meeting featured two speakers seeking to provide guidance for practicing actuaries as they help their organizations navigate these dynamic times.

The first speaker, William Wilt, FCAS, president of Assured Research, explained what is causing the current economic and social inflation affecting P&C insurers. He also discussed what we may expect in a post-pandemic world. The second speaker, William Finn, FCAS, senior vice president and chief actuary of The Hanover Insurance Group, shared practical considerations for dealing with inflation for pricing, reserving and planning from the perspective of a U.S. primary P&C insurer.

Wilt started from the foundational concept of Economics 101 — supply and demand. From the beginning of the pandemic until today, demand for goods has risen while supply declined with supply chain snarls, labor shortages and Russia’s attack of Ukraine. This, coupled with a surge in fiscal spending during the pandemic, resulted in rising economic inflation, in turn prompting the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates, all of which has historically led to recessions.

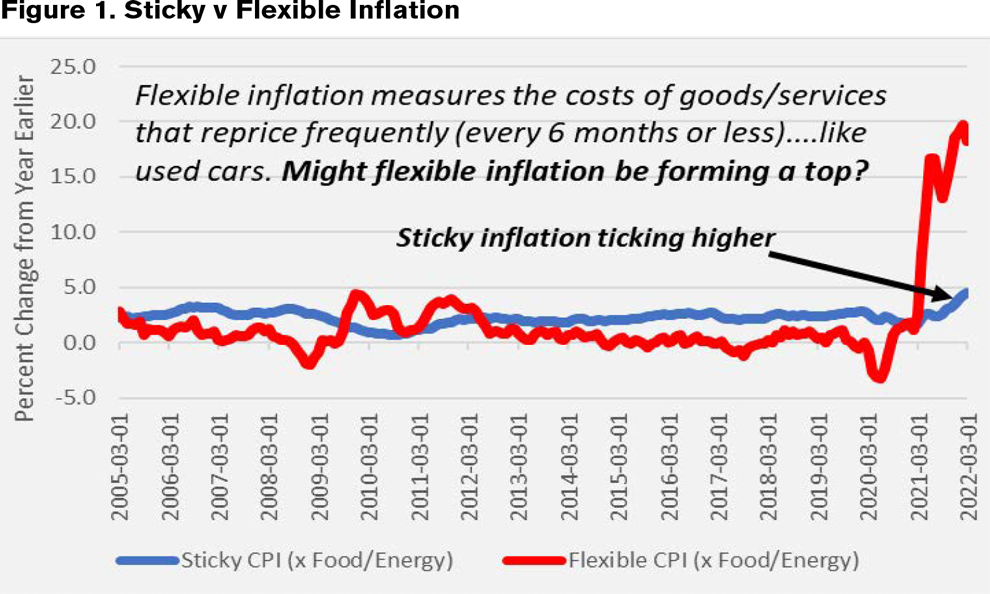

He then dove deeper to differentiate between “sticky” and “flexible” inflation. Flexible inflation measures the costs of goods and services that reprice frequently (every six months or less), while sticky inflation refers to annual contracts like mortgages, rent, medical and education. As captured in Figure 1, flexible inflation jumped early in 2021. Of greater concern, sticky inflation started upward later in 2021. While flexible inflation may come down as quickly as it went up, sticky inflation will require a longer lag to return to prior levels.

As actuaries strive to understand inflationary trends, Wilt shared examples of the explosion of publicly available tools for tracking trends that impact loss costs. The U.S. government provides significant volumes of free data, such as the St. Louis Federal Reserve Economic Database (FRED), which includes thousands of time series across the economic spectrum. Other examples include Google trends, real-time auto crash data, office occupancy indicators, public transportation data, active futures markets and medical costs from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Office of the Actuary.

Wilt then pivoted to social inflation, which he posits matters more than economic inflation because it is harder to neutralize through pricing actions. Civil case filings fell in both 2020 and 2021 because so many courts were closed for the pandemic, with 2021 finishing 21% below the peak in 2019. But Assured Research believes the underlying symptoms driving litigation have only increased during the pandemic. They expect social inflation pressures to return as court activity resumes.

When the liability insurance crisis hit in the 1980s, many states took legislative action to implement tort reforms which helped stabilize the market and improve liability insurance combined ratios. Assured Research does not see major incentives for tort reform today, other than the Florida property insurance crisis. This topic is sufficiently problematic to merit its own concurrent session at the CAS Spring Meeting.

Wilt concluded his presentation with these points about inflation’s impact on the insurance industry:

- History teaches us that the earnings cycle follows the pricing cycle, with combined ratios tending to decline for approximately three years after the peak of each pricing cycle.

- Reserve balances appear broadly healthy, with particular redundancies in workers’ compensation.

- Insurers are adept at neutralizing the adverse impact of inflation through pricing, while investment income rises as interest rates increase.

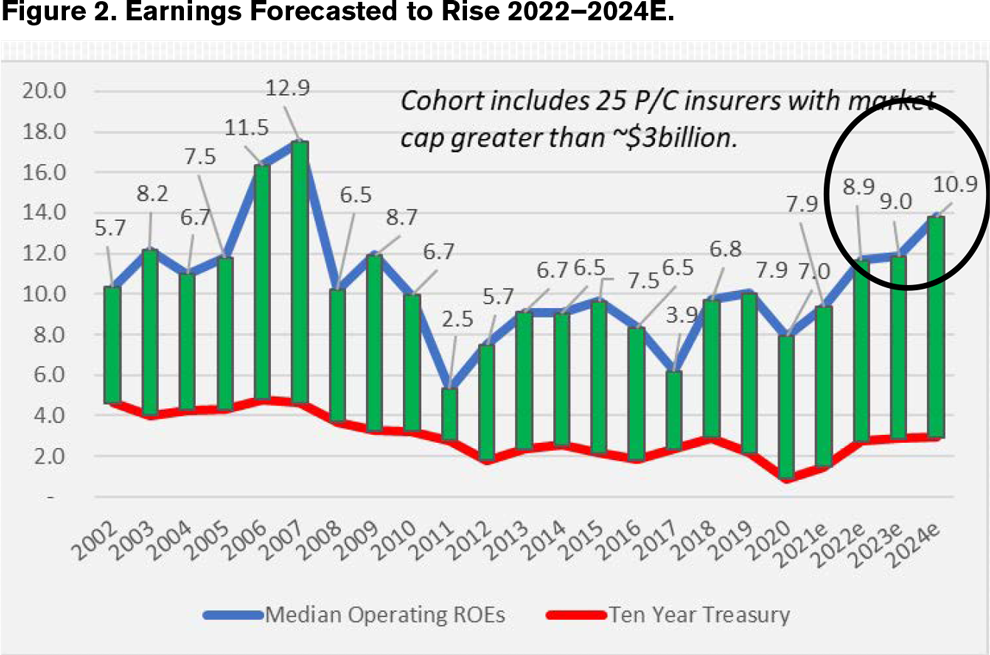

- Therefore, insurers’ ROE can be expected to increase over the next few years, from a low of 7% in 2020 at the beginning of the pandemic to nearly 11% in 2024, as captured in Figure 2.

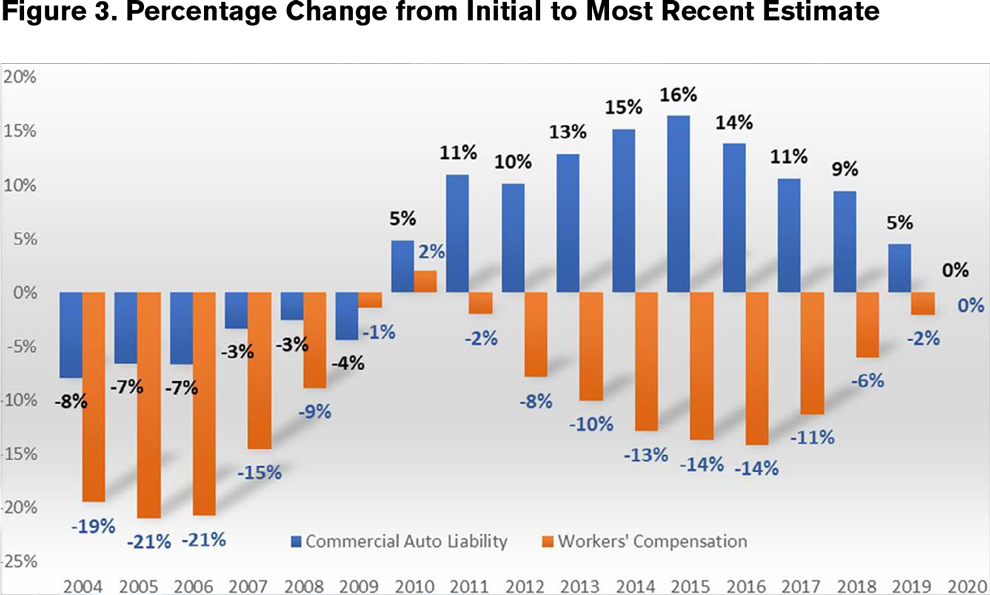

Finn then shared his perspective about how inflation impacts the practicing actuary. Actuaries routinely predict the future by studying the past, and this clearly is more challenging when we are living through a rapidly changing environment. For example, the industry has experienced dramatic reserve development in commercial auto liability and workers’ compensation for nearly two decades, with an inverse pattern between the two lines from 2011 to 2020 (see Figure 3).

He provided a rubric for thinking about the impacts of economic inflation across major lines of business, whether you are responsible for pricing, reserving or financial planning.

- What economic components (e.g., lumber, vehicle parts, medical costs) influence the product line?

- How do we track it (e.g., composite indices, medical CPI)?

- What is the exposure sensitivity (e.g., payroll, building value)?

- What else can we do (e.g., pricing, exposure, forward-looking costs)?

He proceeded to apply this rubric for six major product lines: workers’ compensation, commercial property, general liability, commercial auto, homeowners and personal auto. If we do this well, we can help our companies understand, anticipate and manage through this spike in economic inflation.

Finn then turned our attention to social inflation, which has been prominent in commercial auto because of high limits, at-fault claims, sympathetic plaintiffs and less sympathetic defendants. Traditional backward-looking reserving methods can mistake litigation delays for favorable case development. Claim pattern changes can be missed for multiple planning cycles, and changes in signals can be mistaken for noise.

The pandemic complicates any actuarial analysis trying to identify, quantify and adjust for social inflation. Litigation trends have been slowed for two years now, still not yet back to its pre-pandemic pace. Allocation of medical resources to COVID delayed all other elective and preventative medical treatments. The long-term impacts of COVID survivors are being heavily discussed, but the long-term impacts from delay in all other treatments could be even more impactful to insurance losses.

Finn concurred with Wilt that the underlying environment of litigation financing, outsized jury awards and societal changes have not changed. We need to be watching for the signals of social inflation to determine whether we will experience a gradual resumption or rapid catch-up to pre-COVID trends. Finn closed with this aspirational challenge for all practicing actuaries:

Our job must be more than predicting the future. It must involve discussion of the risks associated with predictions, the signs that those predictions could be flawed, and an acknowledgment of the business impacts of errors in our underlying assumptions. It must also include driving innovation in our thinking and our analytics, and a commitment to developing our young talent to be agile, courageous and broad thinking actuaries and insurance business professionals.

For more of Dale Porfilio’s feature stories on the Spring Meeting, see

Risks Emerge Around Climate-Related Litigation

And

Behavioral Science — A Useful Addition to the Actuarial Toolbox.