We live in a time when most of the global scientific community agrees that climate change caused by greenhouse gases is a reality. Climate change has led to an increase in the temperature of the earth by an average of 1.2° Celsius over pre-industrial levels, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). This measure seems as simple as its repercussions are complex. Global warming has increased the frequency and severity of extreme weather events such as floods, wildfires, and severe convective storms, including hurricanes, hail, straight line winds, and tornados. Higher temperatures have provided more energy for storms, making them more powerful and less predictable.

Meanwhile, melting artic ice has raised sea levels, exacerbating the impact of coastal storms. These extreme weather events have translated into increased risks to civil society and businesses, leading to property damage, business interruptions, and, consequently, an increase in insured losses. Climate change is and will continue to be an imminent risk for many people and businesses — one of the largest sources of insurance expenditures in the immediate future. Beyond insured losses, global warming could risk a climate credit crunch, which refers to the difficulty in borrowing and lending money or accessing financial services (for example, tighter lending standards for energy-inefficient buildings could eventually trigger a more widespread financial crisis). The lines of business that are primarily impacted in terms of magnitude are personal and commercial property, followed by auto lines. In 2024 alone, according to a report by Munich Re, losses from extreme weather events reached $320 billion globally, of which $140 billion were insured. The remaining uninsured amount was left for governments, businesses, and individuals to cover. The magnitude of losses has led to insurers having few options but to limit coverage options or adapt the brute force approach — withdrawing completely from a market. Altogether this has minimized writings in high-risk areas, widening the existing protection gap even further. As significant capital providers in the market, they are uniquely positioned to invest in climate change prevention strategies. Insurance companies, as a business among others that are directly exposed to the risks and costs of climate change, can benefit from climate change prevention strategies — not just from returns on investments, but also by minimizing exposure to insured losses — all while not widening the protection gap for consumers.

Climate change prevention strategies

To manage climate change impacts, there are three commonly used strategies: mitigation, adaptation, and acceptance.

Acceptance is the strategy of employing purely reactive measures to minimize climate change. As the name suggests, acceptance simply recognizes that there will be consequences to climate change and seeks to address those consequences by insuring against them or providing government financial assistance to alleviate their effects. If this strategy sounds familiar, it is because it is the status quo. Insurers practicing the acceptance strategy remain afloat and profitable by transferring risk through high-risk financial instruments such as catastrophe bonds or alternatively by continuing to raise premiums for consumers. While this strategy’s social impact is at its best neutral and at its worst negative, its sustainability is dubious. As extreme weather events become more common and severe, the consequences of climate change are expected to be unsustainable under this insurance model. Simply put, continuing a business-as-usual model is likely going to be insufficient to cover the costs of climate change as they increase at an alarming rate. Although insurers do not have to do much more under this strategy other than introduce new products and rate those products aggressively, the insured losses may soon be so substantial that the model is untenable.

Adaptation, conversely, is a strategy which seeks to adjust to the unavoidable consequences of climate change and help communities manage climate change risks better. Rather than accepting climate change and doing nothing about it, adaptation seeks to avoid the losses of climate change by better preparing for the consequences. For example, to prepare cities for urban pluvial (rainfall) flood risks, the adaptation strategy would dictate restoring watercourses, expanding greenspaces, and introducing porous surfaces that improve storm water management. Adaptation, accordingly, is an investment opportunity, as dollars spent adapting to the consequences of climate change will minimize the losses.

Finally, mitigation — more popularly known as “net zero” — is a strategy that doesn’t just try to prepare for the consequences of climate change, rather it seeks to minimize climate change itself. Mitigation refers to reducing greenhouse gas emissions to limit global warming. While this is certainly the boldest strategy of addressing losses related to climate change, skeptics raise issues about the response time of this strategy, that the effectiveness of the strategy is not guaranteed, and that the damage already incurred to the climate is irreversible. In any event, mitigation serves as another investment opportunity as capital allocators can invest in mitigation measures against climate change to minimize the losses.

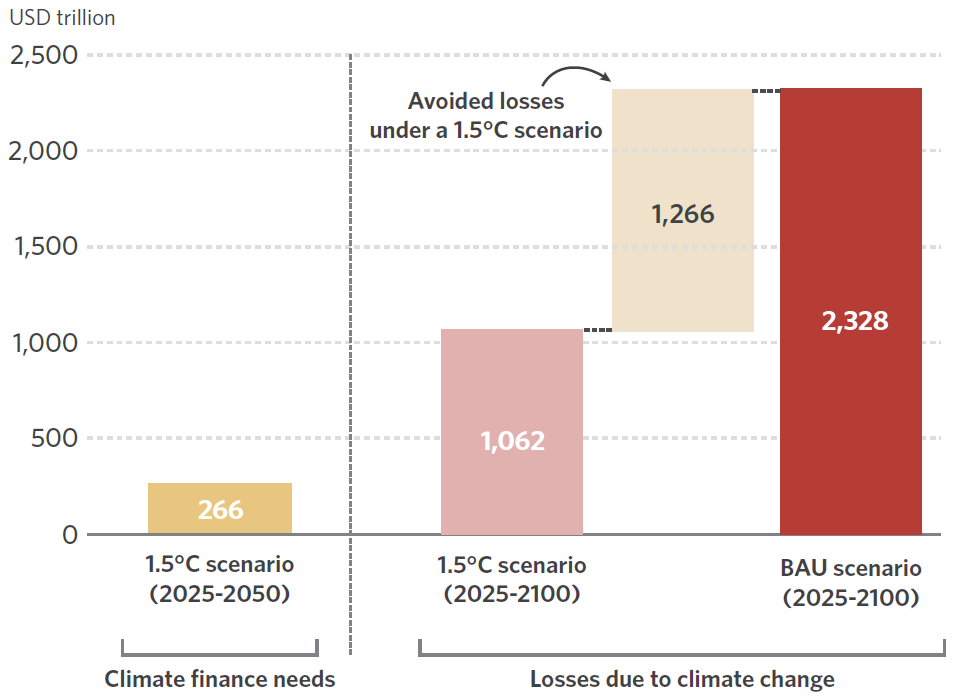

Target levels for climate investment

Based on a study from the Climate Policy Initiative (CPI), it is estimated that the global investment needed to address climate change is $266 trillion between 2025 and 2100. While at first glance this amount seems overwhelming — for reference, the world’s annual GDP is estimated at approximately $100 trillion — this amount of investment needed pales in comparison to the projected costs of losses from climate change under the acceptance strategy. Under the acceptance strategy, the global costs from losses due to climate change for the period from 2025 to 2100 are estimated at $2,328 trillion. These costs include direct economic impact of increased weather-related and other uninsurable damage, increased production costs, productivity losses, and health costs. The CPI also believes that its estimates are likely understated because it does not capture capital losses caused by stranded assets, losses to nature and biodiversity, or those from increased conflict and human migration that cannot be reasonably measured. However, with proper investments in prevention that would restrain climate change, roughly half of those losses could be avoided.

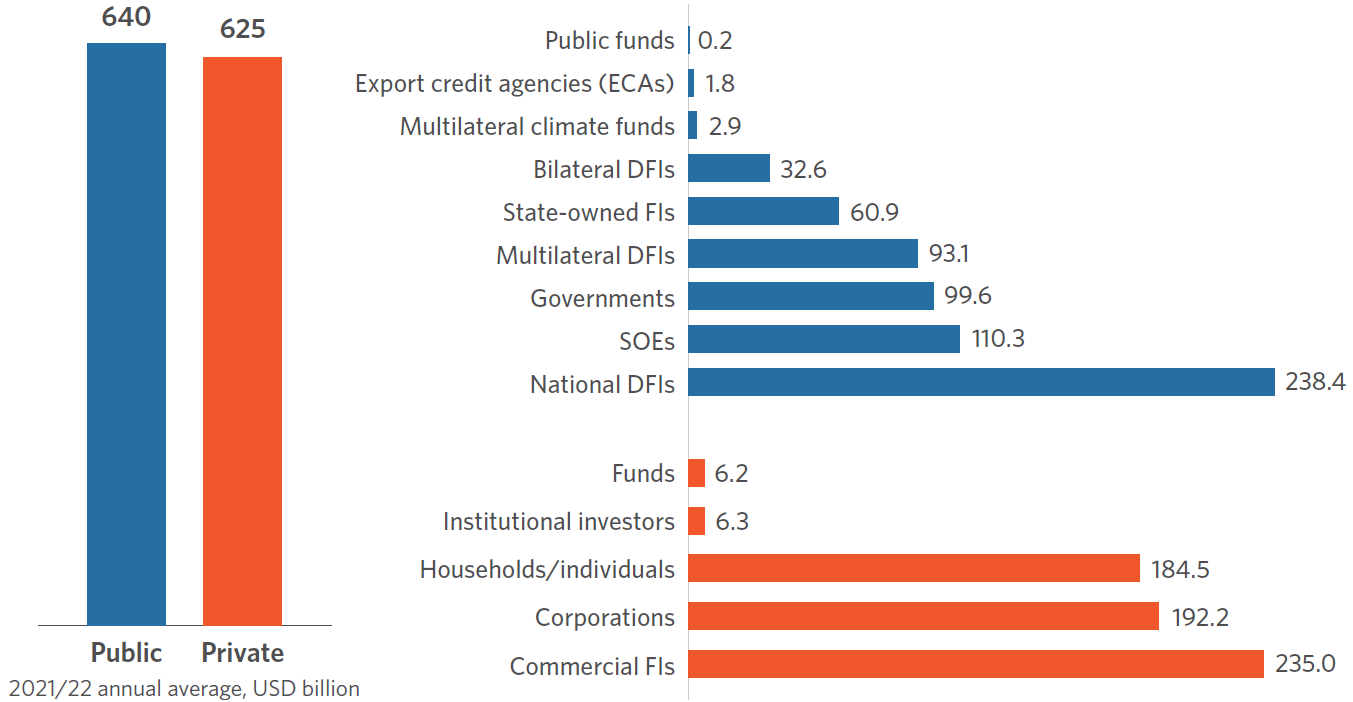

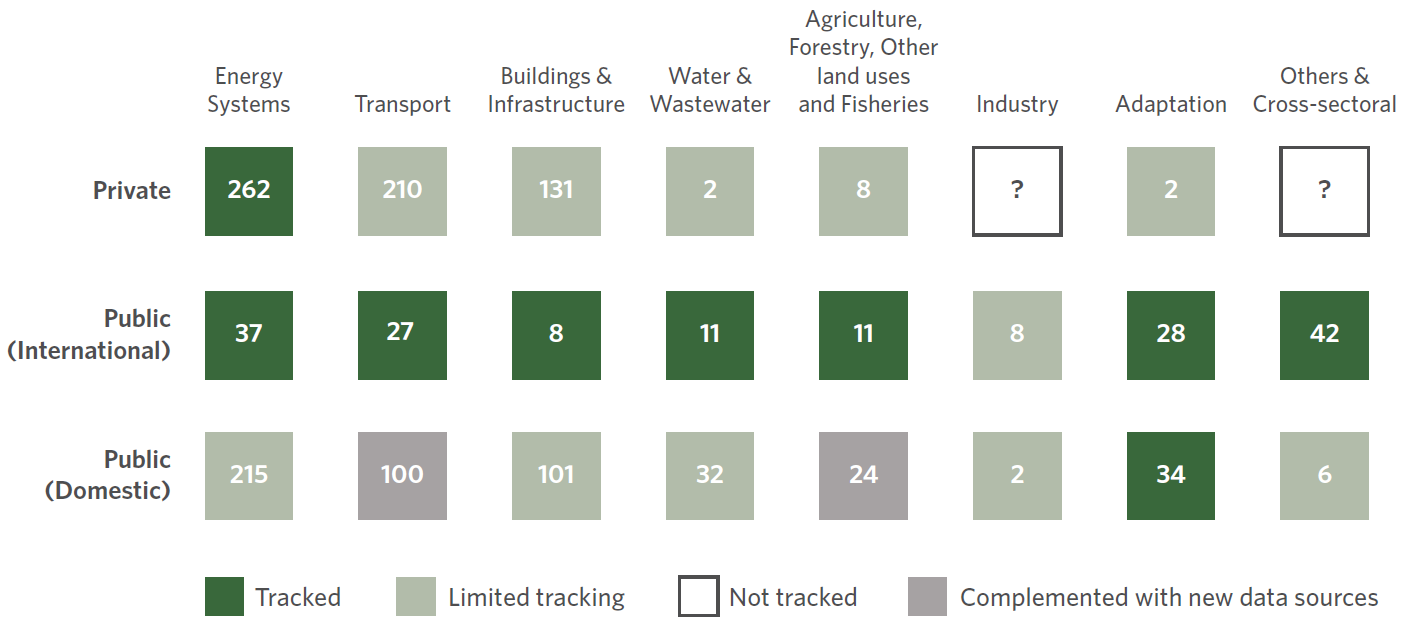

In its study, the CPI estimated that in the years 2021 and 2022, global climate finance approached $1.3 trillion annually compared to $653 billion in the years prior. Most of the growth in funds is allocated toward mitigation strategies, with renewable energy and the transport sector seeing the largest growth. Adaptation finance continues to lag, reaching an all-time high in 2023 at $63 billion and most of the investments in this area dominated by the public sector (around 98%). Despite all this growth, there is still a shortfall and an absence of one major market participant — private insurance companies.

The climate finance conundrum

While private climate finance is growing, it is not yet growing at the rate and scale required. Currently, private climate finance represents approximately 49% of total funds, a significant increase from prior years. However, private climate finance still lags such that it is insufficient to close the funding gap. The source of this investment explains this lag in funding. Rather than institutional investors allocating massive amounts of capital, the largest private sector growth came from individual household spending — driven predominantly by the sale of electric vehicles supported through government policies encouraging the uptake of low-carbon technologies.

While it is certainly necessary for individual households to allocate their spending in ways which adapt and mitigate against climate change, that will not be enough to close the climate finance gap. Even commonly used funding schemes such as public–private partnerships and blended finance, where an agreement between governments and the public sector involving private capital to finance projects up-front and then draw revenues from future tax receipts to repay these loans, wouldn’t solve the issue. Instead, to close the gap, climate finance needs to incentivize private capital to seek returns on investing in climate change action. This means that institutional investors, such as pension funds, investment banks, and insurance companies, need to seek returns on investments in climate finance as opposed to other areas of the market. While two of three of those capital allocators may only reap the benefits of climate finance as a return on investment, insurance companies are poised to reap the benefits as both a return on investment and a reduction on expenditures from insurable losses.

Incentivizing insurance companies

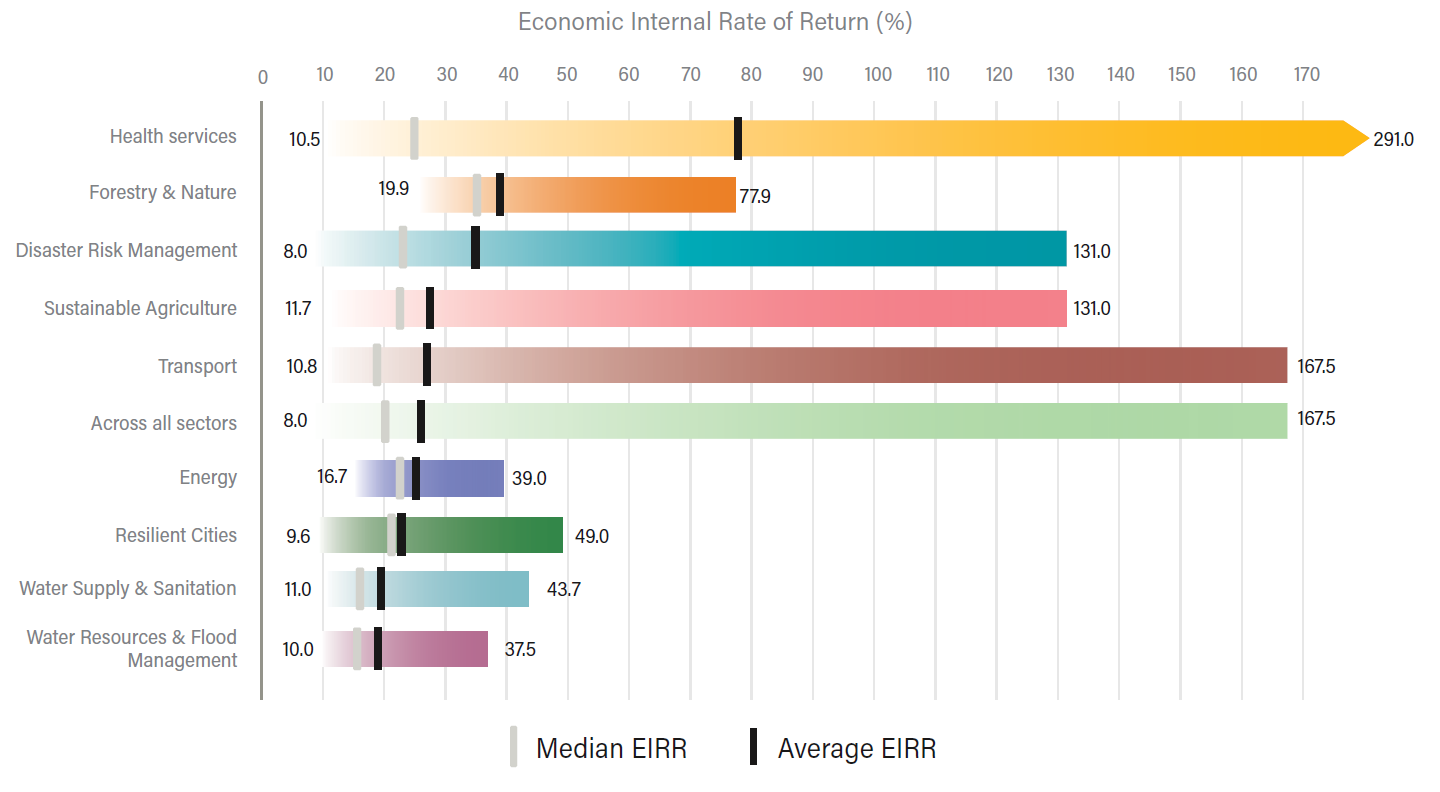

While raising the necessary funds for adaptation remains challenging, especially through private funding, it does create the highest opportunity for returns. Unfortunately, the true value of adaptation remains underestimated because of the difficulty in measuring the returns. For example, the World Resources Institute (WRI) has estimated that the return on investment for adaptation is about $2–$10 in avoided losses per $1 invested over a decade. Likewise, Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) estimates that flood and wildfire standards applied to new construction save $12 for every $1 financed.

However, WRI research uses the “triple dividend of resilience” framework to capture three key categories of returns on adaptation investments: avoided losses, induced economic development, and additional social and environmental benefits — an overarching metric that reveals that the return on investment from certain prevention measures may be much greater beyond simply preventing damage. One example is an urban infrastructure project in Vietnam that aims to reduce flooding and improve water drainage. When estimating the return on this project, many models would consider only the avoided cost of flood damage. However, investments in resilient infrastructure could also increase average land prices, decrease healthcare costs by reducing waterborne diseases, and boost workers’ productivity by reducing travel time, thanks to new and improved roads. The triple dividend framework would account for all these outcomes, offering a more complete picture of the value that adaptation and resilience projects can bring and better incentivizing insurance companies in investing in climate finance.

The WFI has come up with a model of estimates for rates of return on adaptation investments by sector. This is the path forward to establishing measurable financial metrics on investment returns and more accurately estimate the benefits of climate investments. Despite financial institutions such as insurance companies being highly regulated in terms of investment asset classes and their associated risk, with a more established climate adaptation rate of return rubric, new guidelines can be put in place to incorporate climate finance within the risk appetite of statutory limitations on investments.

The way ahead

Better estimations of the return on climate finance, not just from calculating a return on investment but calculating the losses avoided will be essential to incentivizing institutional investments in climate finance to close the funding gap. This is imperative for insurance companies, as otherwise the insured losses which will be incurred from climate change will be so substantial that the very insurance model which operates under the acceptance strategy will soon be unsustainable. The cost of not investing in climate finance to prevent climate-related risks is deemed to be higher than the investments needed to prevent it.

Governments, which have largely focused on mitigation measures, will need to collaborate with insurance companies and focus more on adaptation strategies, leveraging the synergies between the two strategies. Restraints on how and where insurance companies invest their capital will need to be reconsidered if governments seek to properly fund the adaptation measures required to avoid the worst possible outcomes from climate change. If governments, financial institutions, and insurance companies mobilize against climate change and are able to accurately estimate their returns on investing in adaptation measures, then we may be at a turning point of enlisting one of the largest allocators of capital to help address the collective action problem that is presented by climate change.

References

- https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions/.

- https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions/time-series.

- https://gca.org/12-great-examples-of-how-countries-are-adapting-to-climate-change/.

- https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/global-landscape-of-climate-finance-2023/.

- https://www.moodys.com/web/en/us/insights/data-stories/global-climate-finance-gap-cop29.html.

- https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/commentary/article-adapting-to-climate-changes-effects-is-as-important-as-fighting-it/.

- https://www.wri.org/insights/climate-adaptation-investment-case.

- https://www.munichre.com/en/company/media-relations/media-information-and-corporate-news/media-information/2025/natural-disaster-figures-2024.html.

Sandra Maria Nawar is a manager for Intact Financial Corporation in Toronto. She is a member of the AR Working Group Writing Staff.