Ethical Issues is written by members of the CAS Committee on Professionalism Education (COPE). The column’s intent is to stimulate discussion among CAS members. Therefore, positions are sometimes stated in such a way as to provoke reactions and thoughtful responses on the part of the reader. The opinions expressed by readers and authors are for discussion purposes only and should not be used to prejudge the disposition of any actual case and do not modify published professional standards as they may apply in real-life situations.

This article deviates from our familiar format of posing a hypothetical case with questionable circumstances and actions and asking the reader to consider both sides of the case. The following case is based on real events; the names have been changed to protect those involved. The facts imply that ethics were broken or severely bent, so we discuss how an extension to our traditional actuarial ethics relate to the case.

In the early 2000s, An Insurance Company (AIC) bought the reserves of Generic Reinsurance Company (GRC) through a loss portfolio transfer (LPT). AIC did this to be able to show an increase in their carried reserves. Stock market analysts at the time saw the increase of reserves as a good sign, totally missing the disconnect between absolute reserves levels (higher because of new exposures) and increased reserve adequacy. AIC’s strategy worked and was rewarded with an increase in their stock price. AIC’s management thought that taking advantage of the analysts’ poor understanding of reserve adequacy was a fair play.

The reputational damage to both firms was substantial. It affected more than the two companies involved; all of finite risk reinsurance took a reputational beating. As a segment of the reinsurance industry, finite risk reinsurance was never the same.

It was revealed years later that the LPT was always intended to be unwound. Instead of GRC paying AIC for taking on GRC’s reserves, AIC paid GRC to be able to carry the reserves on AIC’s books for a few years. This was documented in a secret side agreement. AIC didn’t buy the reserves, they “borrowed” the reserves instead. The unwinding of that transaction, along with other accounting problems, led to large fines for AIC and legal problems for individuals of both companies who were involved in the transaction.

The reputational damage to both firms was substantial. It affected more than the two companies involved; all of finite risk reinsurance took a reputational beating. As a segment of the reinsurance industry, finite risk reinsurance was never the same. It’s arguable whether there were abuses beyond this case, but nonetheless, many clients steered away from deals that had previously been considered non-controversial because people heard “finite risk” and associated it with this transaction.

This article discusses subsequent guidance that, had it been in place and followed at the time, would have raised critical flags that could have exposed the risks that the transaction posed. If subsequent deals were measured against those flags instead of the tarnished reputation of “finite risk,” the damage to that part of the reinsurance market might have been dramatically reduced. Before we get into that discussion, we will explore the context within professionalism.

“Professional Integrity” headlines the CAS Code of Professional Conduct as Precept 1. Building beyond that key element of integrity, ethics encompasses other components of actuarial mores. That broader scope combines the Code of Conduct, Statements of Principles and Standards of Practice that can be viewed as a collection that defines our actuarial ethics.

“Complex Structured Financial Transactions (CSFT)” (OCC Bulletin 2007-1), a bulletin of the U.S. Department of the Treasury, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, draws attention to elements in transactions that could give rise to heightened legal or reputational risks. It applies to structured financial transactions in many industries but was likely motivated by problems in the banking world. The insurance industry has its share of conceivable problems, though this article only addresses a couple examples.

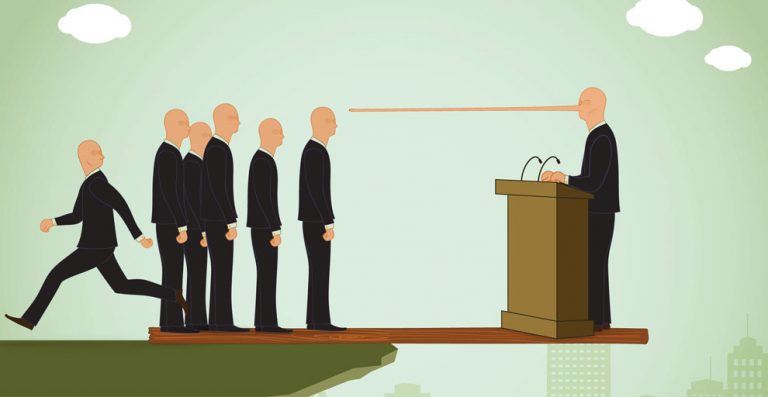

After reading this article, consider if you recall cases where actuaries challenged such offences. A natural desire to please clients combined with pressure from company management, stockholders or boards of directors to produce profits warrants a reminder of potential pitfalls.

The LPT transaction outlined above raises questions on each of the features in the CSFT bulletin.

The CSFT bulletin warns against undocumented (or secret) side agreements. Without knowing about the side agreement in this case, the whole nature of the LPT looked normal and appropriate. With knowledge of it, the actual operation of the transaction exposed other flagged features.

Because of the secret side agreement to unwind the transaction, there was in fact no lasting economic substance. The stated business purpose of the LPT — to transfer GRC reserve risk to AIC — was a mirage.

The bulletin flags concerns if there is lack of economic substance or business purpose. It further highlights the particular concern of circular transfer of risk. The AIC-GRC deal appeared to be substantial. LPTs are valuable to manage loss risk, control the size of liabilities in the balance sheet, and achieve reserve diversity or reduce volatility. Yet because of the secret side agreement to unwind the transaction, there was in fact no lasting economic substance. The stated business purpose of the LPT — to transfer GRC reserve risk to AIC — was a mirage. The undisclosed business purpose was to increase the reported level of reserves without AIC actually taking on the reserve risk itself. That was the circular transfer of risk. The LPT appeared to transfer reserve risk to AIC, then the side agreement guaranteed that GRC would take the risk back.

The bulletin also flags questionable accounting, tax or regulatory objectives. In this case, the goal to post reserves was a reasonable objective. But the bulletin also warns that the accounting needs to follow the substance of the transaction. In this case, AIC reported the transaction inconsistent with the substance of the deal by not accruing for the return of reserves that would happen once the side agreements were fulfilled. An interesting element here is that the accounting treatments of AIC and GRC were different. AIC accounted for the LPT as reinsurance, while GRC accounted for the transaction as a deposit. Because there was insufficient risk transferred, deposit accounting was the appropriate treatment of the deal. Despite correct accounting by GRC, the reputational and legal problems landed as much on them as they did on AIC.

The bulletin warns of two other characteristics that could give rise to increased reputational risk. Material economic terms outside of market norms could signal suspicious behavior elsewhere. Also, disproportionate compensation relative to the risk transferred or services provided might flag a potential problem. Elements of the AIC-GRC transaction could have triggered either of these two flags. What would the right price have been for a full risk-transfer LPT? Was the fee paid to the reinsurer for the side agreement appropriate for borrowing reserves?

For purposes of playing out the issues, this article is using an extreme case. Actuaries often face similar questions with more subtlety.

A recurring example is the use of commission swings where the commission adjusts based on actual experience. They work by the setting minimum and maximum commissions that would be payable for poor or good experience, respectively. Initially the commission payment equals a provisional rate somewhere between the min and max. Commission pays for the reinsurers’ share of insurance company expenses. When higher than those expenses, it creates an override to reward the company for sharing their good business. When lower, it creates a burden on the company since they will need to pay for expenses from other business or even policyholder surplus.

Actuaries’ obligations go beyond the parties involved in transactions. Many of the CFST-inspired questions can remind us why the public needs actuaries.

Actuaries’ obligations go beyond the parties involved in transactions. Many of the CFST-inspired questions can remind us why the public needs actuaries.

Commission swings could create potential reputational problems in two main ways.

- By its nature, a commission swing creates a circular transfer of risk. As reinsurers pay more loss within the range of the swing, those losses are reimbursed by the ceding company through return commissions. If the minimum commission is significantly below the company’s expenses, the insurer and reinsurer should be sure that the company can afford the extra share of expenses they would need to cover. If the company can’t afford that reimbursement, then they wouldn’t be adequately protecting their surplus despite having reinsurance in place for that very purpose.

- If the company fails to accrue for return commissions after losses would require it, then they would be misstating their financials. While this is an accounting failure, sometimes actuaries are best positioned to notice the risk and should communicate it to assure accounting follows the substance of the contract terms.

Here are some questions motivated by the CSFT bulletin that both the insurance and reinsurance actuaries should consider for commission swings.

- Can the insurance company afford to accrue for return commission and will they appropriately do so?

- Is the objective of the commission swing to encourage the regulator to allow a company to operate with excessive leverage?

- Are the terms consistent with market norms?

Actuaries’ obligations go beyond the parties involved in transactions. Many of the CFST-inspired questions can remind us why the public needs actuaries. Actuaries’ professional guidance can help them recognize misleading or overly complex transactions that create insolvency risks otherwise hidden.

Suggested further reading within the actuarial ethic are the Code of Conduct, Precept 1 on “Professional Integrity” and Precept 13 on “Violations of the Code,” as well as ASOP 7 on “Analysis of Insurer Cash Flows.”